Jim Fitzpatrick’s art has been an important influence on muraling in two ways.

The first is his role in popularising Alberto Korda’s “Guerillero Heroico” photograph of Ernesto “Che” Guevara by creating a striking two-tone print in red and black. The photograph itself was printed as a poster, but Fitzgerald’s stylised version of it is more dramatic and easier to reproduce, particularly in any context or medium – such as murals – where an exact reproduction of the photo would be difficult.

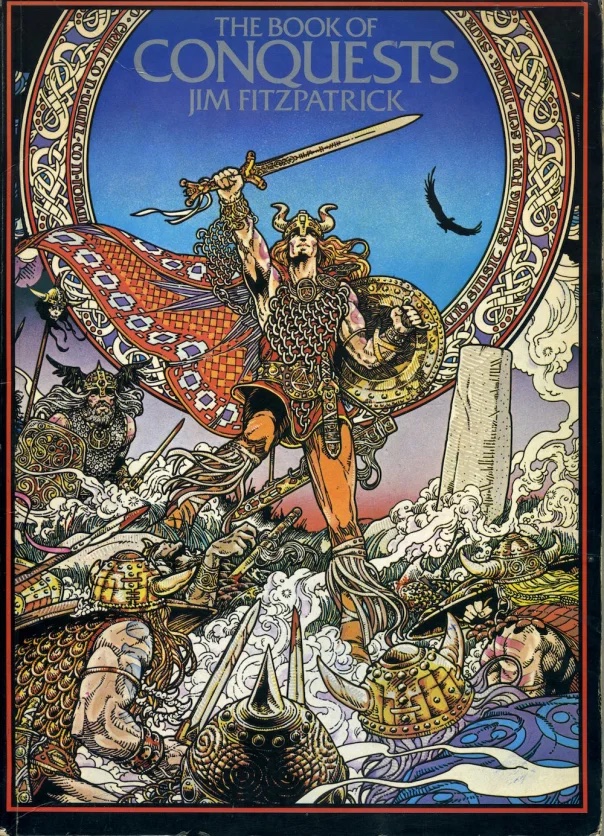

The second is Fitzpatrick’s Celtic artwork. In 1978, Fitzgerald published The Book of Conquests, the first volume of his retelling of the twelfth-century Irish text Lebor Gabála Érenn, the Book Of The Taking Of Ireland or (if you’re a Horslips fan) The Book Of Invasions, which told of the clashes between the Fır Bolg and the incoming Tuatha Dé Danann at the Battle Of Moy Tura. Fitzpatrick translated the work and provided his own telling of the dramatic tales, but even more striking were the lavish and detailed illustrations that Fitzpatrick used to accompany the myths. Both the stories and the images presented a dazzling and vibrant vision of pre-Christian (and pre-British) Ireland.

We introduce each of these and their initial appearances in muraling in the late 1980s in Derry, Strabane, and Belfast. Then we present a chronological gallery of additional images of both types. There is a brief final section on the use of Fitzpatrick’s work in connection with the Cruthın.

Viva Che!

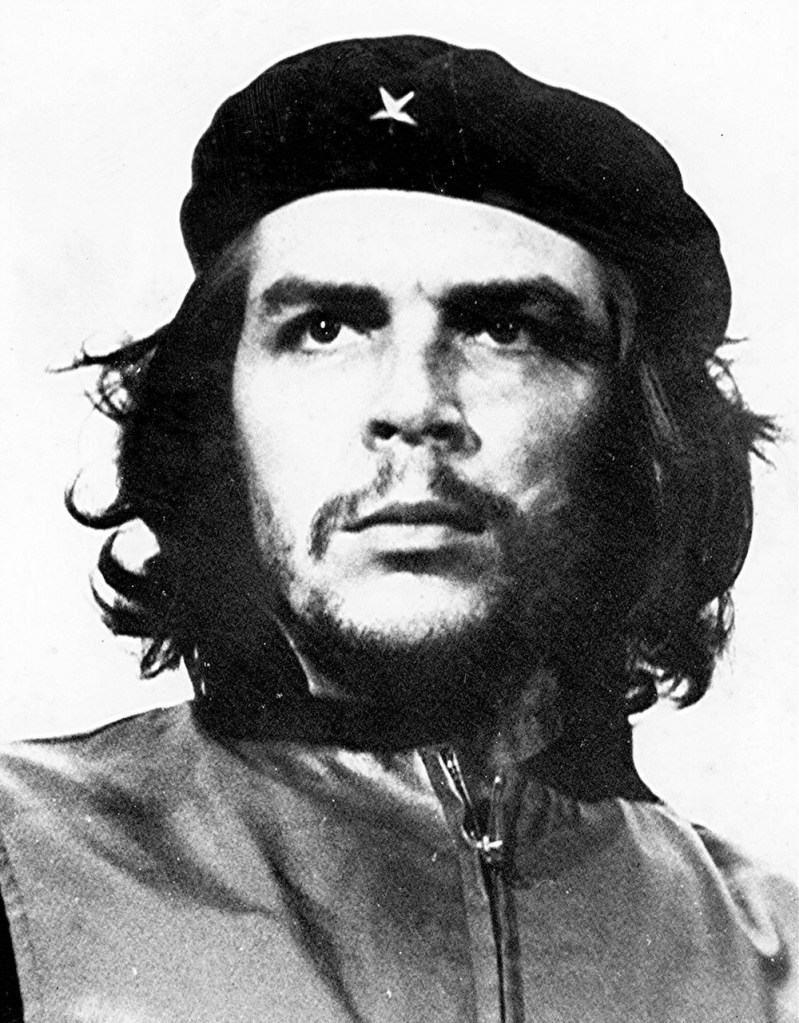

Henri Cartier-Bresson said of Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s eyes that they “glow; they coax, entice and mesmerize.” (WaPo), and he described Che as “an impetuous man with burning eyes and profound intelligence who seems born to make revolution” (in a special feature ‘This Is Castro’s Cuba Seen Face To Face‘ that Cartier-Bresson shot for Life magazine).

These descriptions fit the iconic “Guerrillero Heroico” photo by Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez – better known as Korda – of Che in Havana, Cuba, in 1960, taken when Che was 31.

By March 1960, when the photograph was taken, Che had already travelled thousands of miles throughout south and central America, been in Guatemala during the overthrow of the Árbenz government by the United States on behalf of the United Fruit Company, and taken part in the Cuban revolution against Batista, becoming Minister Of Finance in the Castro regime. On the day that the photograph was taken, he was attending the funeral service for 27 of the 75-100 victims of the explosion of the freighter La Coubre.

In Cuba, the photograph was not immediately published but appeared on two occasions in 1961 in a small (one-column) announcement for a talk to be given by Che. (The early history of the photo in Cuba is described in Ziff 2005, Ziff’s documentary film Chevolution, and Gott 2006.)

It reached Jim Fitzpatrick when Jean-Paul Sartre, who had met Korda and Che in Cuba in 1960 and attended the La Coubre memorial service, gave a copy of the photo to the Dutch anarchist group “Provo” who published a magazine of the same name that Fitzpatrick read (Ziff 2005 | Aman interview). Fitzpatrick used Korda’s photograph to produce a psychedelic Che for a feature in the June/July, 1967, edition of the Dublin magazine Scene.

This profile was not published – the magazine owner objected to the accompanying verbiage, in particular (youtube). But when Fitzpatrick later launched a poster company, Two Bare Feet, the psychedelic Che was sold as a poster. (See also the magazine article – presumably from Scene – about the new company, on Jim Fitzpatrick’s blog.)

In France, the photograph appeared in August, 1967, in the French magazine Paris Match (Image at The Conversation). Korda is not credited and it is not known how it came to be in the magazine.

Che’s diary from the Bolivian campaign, which had been recovered when Che was captured and executed in October, 1967, was published in Italy in 1968 with a black and white image of the photograph on the cover; posters of the Guerillero Heroico were printed as publicity for the book (Smithsonian Magazine says “millions” of these posters were printed and sold; the Guardian says “thousands”). If the image of Feltrinelli at an Italian demonstration shows this poster (image removed), it was a photographic-quality version. (The first UK edition of the Bolivian Diary (from Cape/Lorrimer in London) did not use any version of the Korda photograph on its cover (etsy).)

In 1968, Fitzpatrick used a better-quality copy of the Korda photograph from the left-wing German magazine Stern to create the now iconic version that was printed on red, with a hand-coloured yellow star (Mir interview | youtube). In relation to Korda’s photo, Fitzpatrick raised the eyes slightly and added an “F” (for “Fitzpatrick”) on Che’s left shoulder (WP).

Fitzpatrick printed a thousand copies of his poster and they were distributed to leftists in England and in Europe. In more mainstream media, it was published in Private Eye and from there it appeared (in acrylic on board) in a London exhibition called “Viva Che” alongside the psychedelic version (perhaps the silver-foil version which can seen at V&A). Gerard Malanga used it (still in 1968) to produce a series of nine Ches in pop-art colours that he attempted to pass off as created by Andy Warhol. Warhol was alerted and claimed the piece – and its royalties (Warholstars | WikiArt).

Here is Fitzpatrick (in later years) with a reproduction of his 1968 ‘Viva Che!’ print. (“Viva Che!” is also the name for the poster of the first (psychedelic) Che but is used from here on to refer specifically to the 1968 poster/print.)

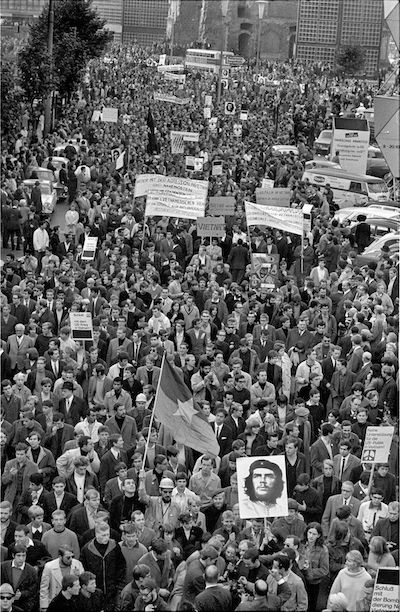

Che’s execution motivated not only Fitzpatrick but sympathetically coincided with and inspired the wave of protests in cites around the world in 1968: “the psychodrama of 1968 arguably opened with death of Che Guevara in the fall of 1967”, wrote Christopher Hitchens. The Korda photograph in its various forms was used to add Guevara to the pantheon of heroes that inspired students and workers across Europe.

The image below shows the Che photograph being carried at a West Berlin protest against the Viet Nam war. See also Munich, 1968 (photo) | Rome 1968 (photo) | Mexico City, 1968 (hand drawn) | Kiel, 1968 (intermediate-level quality, clearly a print but with more detail than the Viva Che!) | Paris, 1970 (simplified).

In the north-east of Ireland, the civil rights movement was aware of, and saw itself as a part of, the wave of protests that took place in 1968. Eamonn McCann cited “the black struggle in the US, the workers’ fight in France, the resistance of the Vietnamese, the uprising against Stalinism in Czechoslovakia” (in McCann, as cited by Prince 2006). (Irish republicanism identifies with many international struggles – see the Visual History page on International Solidarity.)

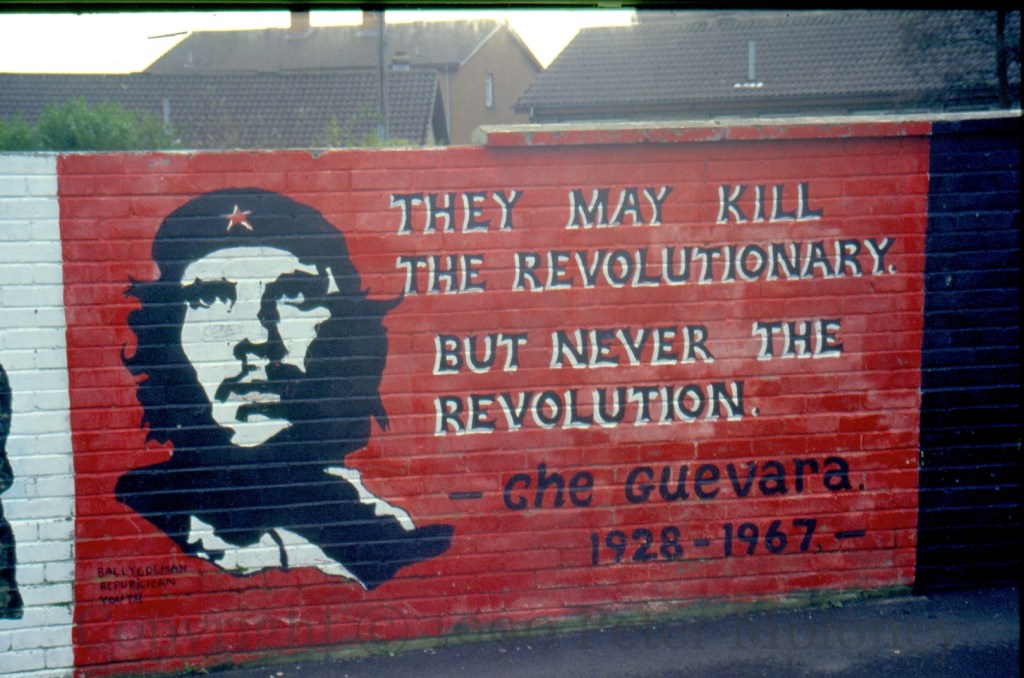

As an anti-imperialist and guerrilla fighter, Che was a hero and inspiration to revolutionary causes across the globe, including Irish republicanism and the armed conflict pursued by the IRA and INLA. Gerry Adams speaks about seeing Fitzpatrick’s Viva Che! in the Chevolution documentary. And Fitzpatrick’s version of the photograph provided the blueprint for how to produce it in large-scale wall-paintings.

(Other Fitzpatrick posters were also well-known to republicans, as he did work for republican/nationalist organisations – the Republican Clubs/OIRA/Workers’ Party (Joe McCann, Kevin Barry, McCormack & Barnes, Resist Repression) and the People’s Democracy/”PD” (People’s Festival) – during the 1970s.)

In (the Republic Of) Ireland, Che’s history was well-enough known that it could be used as a short-hand for debates over workers’ rights and as a pejorative with which to dismiss would-be radicals. According to Sheppard (Che Guevara And The Irish), it then became increasingly associated with the northern conflict – with republicans who were willing to commit violence in pursuit of political goals – while Che’s family connection to Ireland fell from mention.

The first appearance of Che in a wall-painting appears to be this 1988 mural in Westland Street, Derry. (Rolston 2009 “The Brothers On The Walls” concurs.) The “heroic” Che in military beret appears alongside what was becoming the canonical image of Bobby Sands: a long-haired Sands in civilian clothes, smiling. The Comandante star on Che’s beret is red rather than yellow, reflecting the Marxist-Leninist ideology of the INLA/IRSP. On the right of the mural, Lenin appears to be perched on a tank as he addresses an audience of soldiers, two carrying pikes (1798) and another a rifle (1916).

Three early instances of the Heroico/Viva Che! appeared in Strabane, two in the Ballycolman estate and one in Fountain Street. Artists unknown.

Fountain Street:

More images are included below in Additional Images – 1990 To The Present.

Celtic Art

Fitzpatrick began painting mythical Irish figures as a child through the lens of US comic-strips, before adding as influences Irish illustrator (and stained-glass artist) Harry Clarke, English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, the Czech artist Alphonse Mucha, Japanese “ukiyo-e” print-making, and the Book Of Kells (RTÉ interview with Fitzpatrick in 1982). Fitzpatrick also mentions Roger Dean and Ivan Bilibin in a blog post on his site. Connolly (2011), who investigates many of Fitzpatrick’s influences, also includes Gustav Klimt in the basic list.

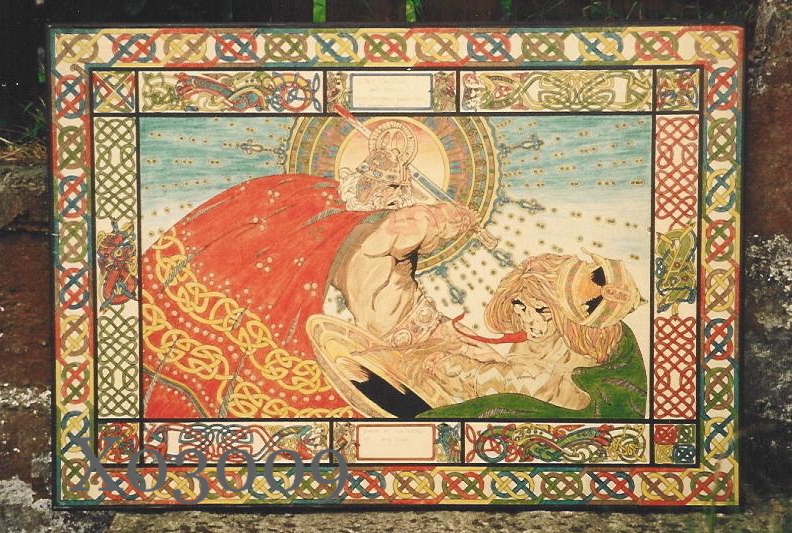

In 1975, a number of Fitzpatrick’s Celtic-themed posters and drawings were published in a portfolio-book Celtia. In 1978, The Book Of Conquests was published in paperback in the USA and Europe, where it was translated into four languages besides English. The second volume in a proposed series of three was published in 1981 as The Silver Arm.

The Book Of Conquests was in the H-Blocks in 1983 when Gerard Kelly (later known as “Mo Chara”) was serving time. Here is Kelly describing the impact Jim Fitzpatrick’s Celtic art had on him:

“One day in 1983, when I was in H-3, I happened to say to John Nixon, one of the first hunger strikers, “Do you have any books on Celtic art or Celtic mythology?” And he gave me The Book Of Conquests by Jim Fitzpatrick. It was a revelation! I just fell in love with that book. I loved the story, I loved the colour. Jim Fitzpatrick’s illustrations were magnificent! Inspiring!

“It was the first time in my life I saw Irish people portrayed as strong, beautiful, honourable men and women. Up until opening that book, I had been told we were the drunken Irish bog-trotters and savages out of Punch cartoons. We live in the six counties where we are taught British culture. We know more about British history than we do about Irish history. “The Irish were only civilised when British democracy came over.” We had centuries of constant demonisation. The Book Of Conquests was the first time I saw our culture and our history presented as beautiful and strong. To me, Jim Fitzpatrick’s work was positive, fantastic, a liberation! As an artist, that book changed my life.

“I had never heard the story of King Nuada before. Then I read the story. Wow! What a yarn! Nuada Of The Silver Arm is one of my favourite stories. As one of the Tuatha Dé Danann you had to be whole and physically perfect to hold the kingship. Nuada lost an arm in the first battle of Moy Tura and so he lost his kingship. He went into the other world, to middle earth, fought through trials and tribulations until Dıan Cécht made a silver arm for Nuada and he was restored to the kingship for another twenty years. But the moral of the story to me was that, no matter what happens, get up again and fight back. No matter how bad the situation you are in, you get back up and fight again. Do not let people isolate you. Get up and fight again. It was very inspiring!”

(Painting My Community/An Pobal A Phéınteáıl – English-language version available for free)

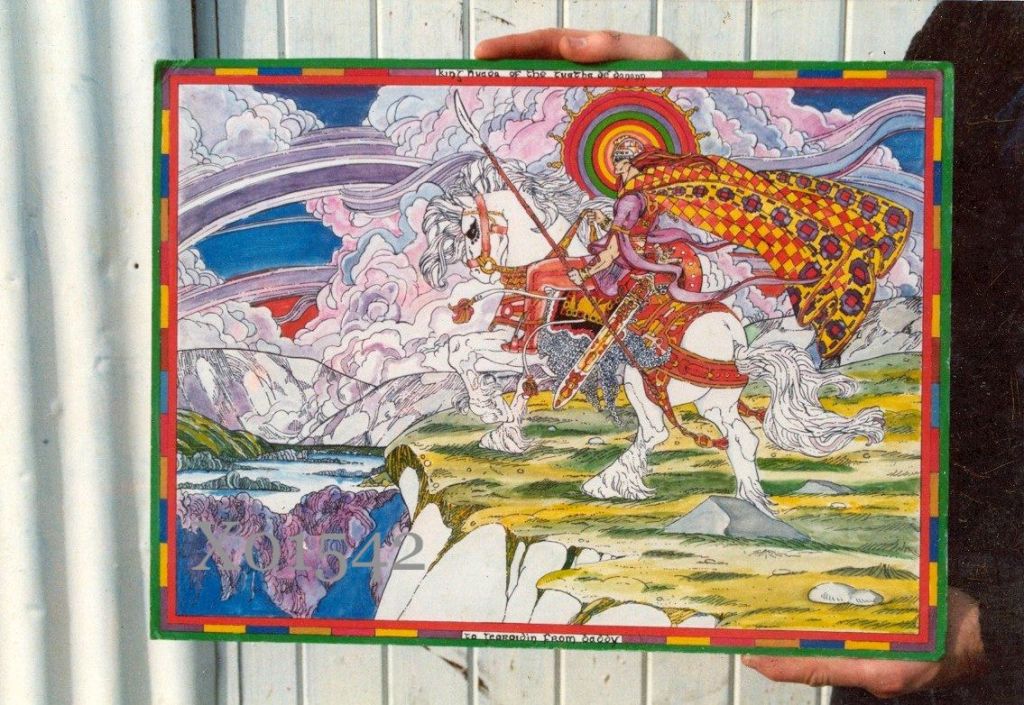

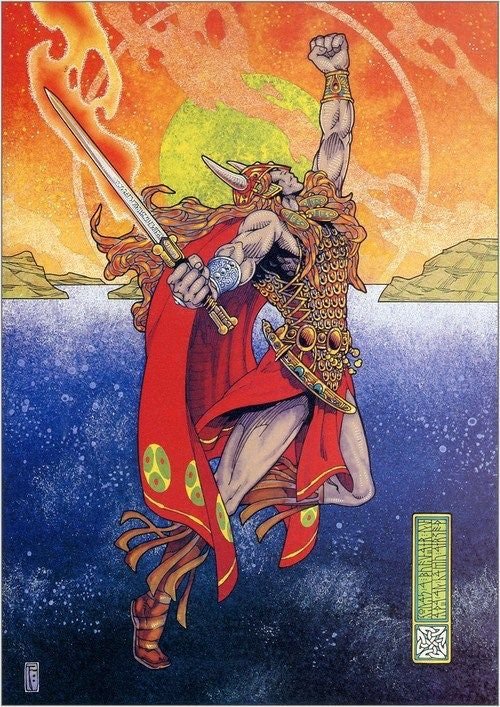

The front cover of The Book Of Conquests is part of larger image ‘Nuada The High King‘ but the central figure of this image would appear in several murals.

Gerard started incorporating Fitzpatrick’s imagery into the art he was producing in prison:

“I traced one of Jim Fitzpatrick’s pictures of the Fır Bolg before they went into battle with the Tuatha Dé Danann from The Book Of Conquests. It’s a close-up profile of a warrior [Bres The Beautiful] going into battle with a line of warriors behind him with spears pointing up into the sky. I liked the detail and traced it with the intention of painting it for someone and sending it out of jail but then the Great Escape happened. All art and craft materials were confiscated. Lock-down.”

Fitzpatrick’s original can be seen here. This image also appeared on the cover of issue #1 of Elenna in 1984, drawn by “P O’Neill”.

Gerard’s tracing of a serpent from The Book Of Conquests was later used in the 1996 Moy Tura mural and the 2008-2010 (Whiterock) Nuada mural (both included below).

‘Nuada Before The Battle Of Moy Tura’, painted in prison by Gerard for daughter Gerada’s fourth birthday, 1983.

‘The Dream Of Nuada’ “on white artistic cardboard … It took me about two months to do that.”

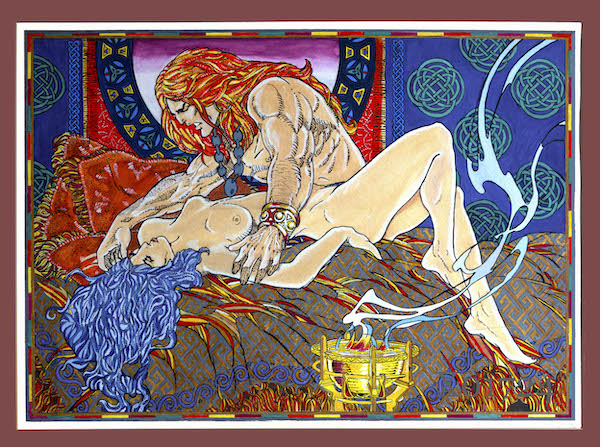

‘Dagda Finds His Mark’ – later chosen for a mural but unfinished – see below.

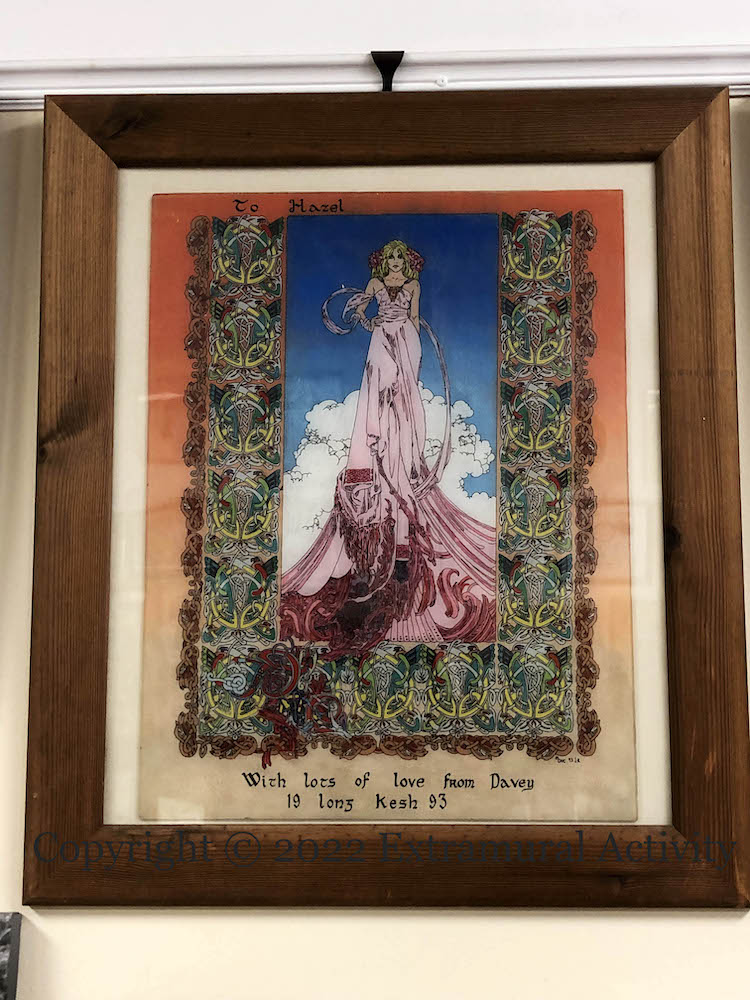

Other prisoners have produced Celtic works by Fitzpatrick. This mirror-image version of Fitzpatrick’s Érıu – “to Hazel, with lots of love from Davey, Long Kesh 1993” – hangs in the Ex-Prisoners Centre (Fb) in William Street, Derry.

Gerard was released from prison in October 1985 and began painting murals in 1987, starting with two portraits of Gerry Adams, Sınn Féın candidate for Belfast West in the UK general election in June of that year. His third mural was a tribute to the eight IRA volunteers who were ambushed and killed (along with one civilian) in May by SAS soldiers at Loughgall. The centre of the mural is based on a poster but the style and colour were inspired by Fitzpatrick’s art. “The Loch gCál mural took us two months to do and I had all the kids in the community working on it.”

The next mural copied the figure of Nuada from Fitzpatrick’s ‘Nuada Journeys To The Underworld‘ surrounded by other elements from Fitzpatrick’s work, such as a dolmen and standing stone, all in the style and colouring of Fitzpatrick.

Mo Chara explained his choice of this image as follows:

“The first thing any colonialist does, in any country, is to take the native culture, including its language, and replace it with theirs. The role of the colonist is to make the native people feel bad about their own culture, persuade them through military, legal, economic, social and every other means to abandon their language and culture and adopt the ways of the oppressor. Our kids get Batman and Robin, Sir Lancelot, Robin Hood. They’re all English or American; they’re not our heroes. I wanted the kids to take pride in Irish history and Irish culture.

“So, I decided to paint a mural about King Nuada. I wanted to surprise our kids into asking, “Is that king ours? We had kings in Ireland? Are you serious?” The kids loved the story of King Nuada and the Tuatha Dé Danann, the fact that he had lost his arm in battle, that he got a new arm, that he had to go through all the trials and tribulations. All those old stories have meanings, there’s a message in them. In this particular one, that this hero was a king who — even though he lost his arm and after that lost his kingship — never lay down. He went through the otherworld, fought Balor of the Evil Eye, won his silver arm and came back, and was as strong as he ever was.”

Additional Images – 1990 To The Present

Gerard/Mo Chara’s unfinished mural of ‘Dagda Finds His Mark’ in Springhill: “That was one of Jim Fitzpatrick’s paintings. We painted it at the top of Springhill. While we were painting it the British army drove across the top of Springhill and fired two plastic bullets at us. One bounced off the wall and one bounced off the ladder. So, we withdrew valorously. Other stuff came up and we never got it finished.”

A ‘Núada’ in Unity flats, Belfast, showing Núada and Morrígan from Fitzpatrick’s ‘Beneath The Sky Of Stars’ below Senach The Spectre, c. 1990. Artist unknown.

The image on the left, from Lurgan, probably during the 1990s, is labelled “Cú Chulaınn Cróga” but depicts Fitzpatrick’s Nuada Of The Silver Arm. The image was much later (c. 2014) used again in Creggan, Derry, but with a hurl instead of a sword.

left: D00510

The long upper wall on Beechmount Avenue, Belfast, was painted – artist unknown – circa 1992 with various pieces from Fitzpatrick’s Book Of Conquests, including the central figure from the cover. The final panel shows Fitzpatrick’s Lough Derravaragh/Children Of Lear.

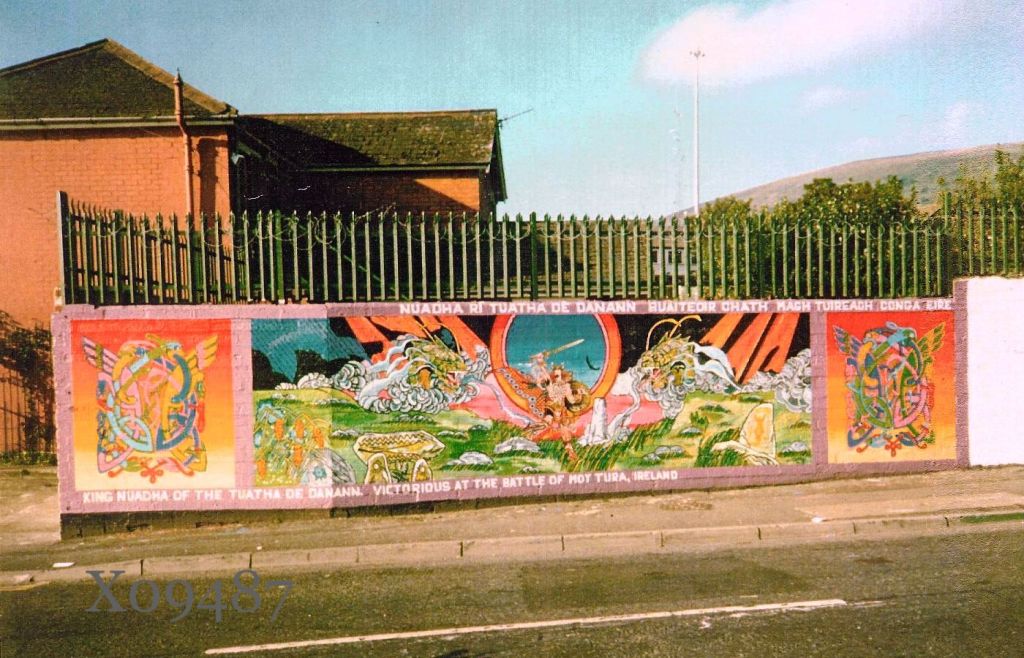

Mo Chara’s mural entitled King Nuada Of The Tuatha Dé Danann Victorious At The Battle of Moy Tura, Ireland reproduces the cover of The Book Of Conquests in the middle and adds various other elements. Upper Whiterock Road, west Belfast.

The main figure is Fitzpatrick’s The Coming Of Lugh and the two horsemen on the left are from Lugh The Il-Danna. Ardoyne, north Belfast. Artist unknown.

This Falls Road board is a comment on the “traditional routes” taken in Garvaghy (Portadown) and Ormeau (south Belfast) and other small towns by the Orange Order – which now pass through CNR areas. The horse comes from Nuada And Indech At Moytura and the landscape is from The Tuatha Dé Assemble For Battle.

Fitzpatrick’s Breas ⁊ Cú Brea in Creggan, Derry. Artist unknown.

Che is the corner image of a ‘Cuba-Ireland’ mural in Shiels Street, west Belfast (1998). Painted by Mo Chara (on the pavement), a Short Strand artist (on the scaffold), and Marty Lyons. In the second image, the republican prisoners, including Sands, are reading a book of Che’s writings.

Viva Che! on a board in Ballycolman, Strabane. Artist unknown.

Che Guevara orders the police service out of the Bogside. Lecky Road, Derry. Artist unknown.

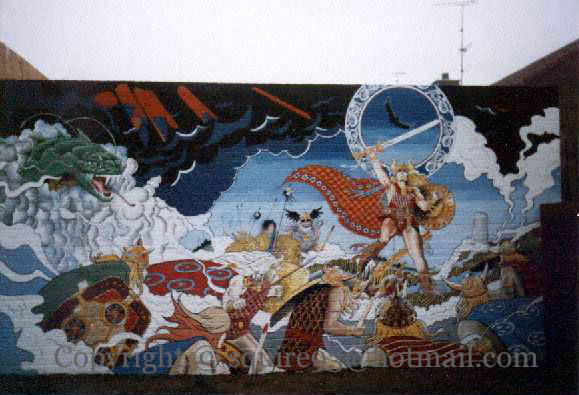

Two panels of about eight in the alley between the Falls Road and Ross Cottages depict pre-Christian Ireland. The Fitzpatrick influence in the first panel is clear (the flying boats) but none of these figures appears to be by Fitzpatrick; so, there might also be some other influence(s) here too (Thundercats/He-Man from the 80s?), particularly in the representation of Balor. The left of the second image reproduces part of a the label Fitzpatrick produced in 1988 for Rosc “mead” and the right reproduces Nemed The Great. Artist unknown.

Fitzpatrick’s Palu The Cat Goddess was used to represent Queen Méabh in Ardoyne, north Belfast. Artist unknown.

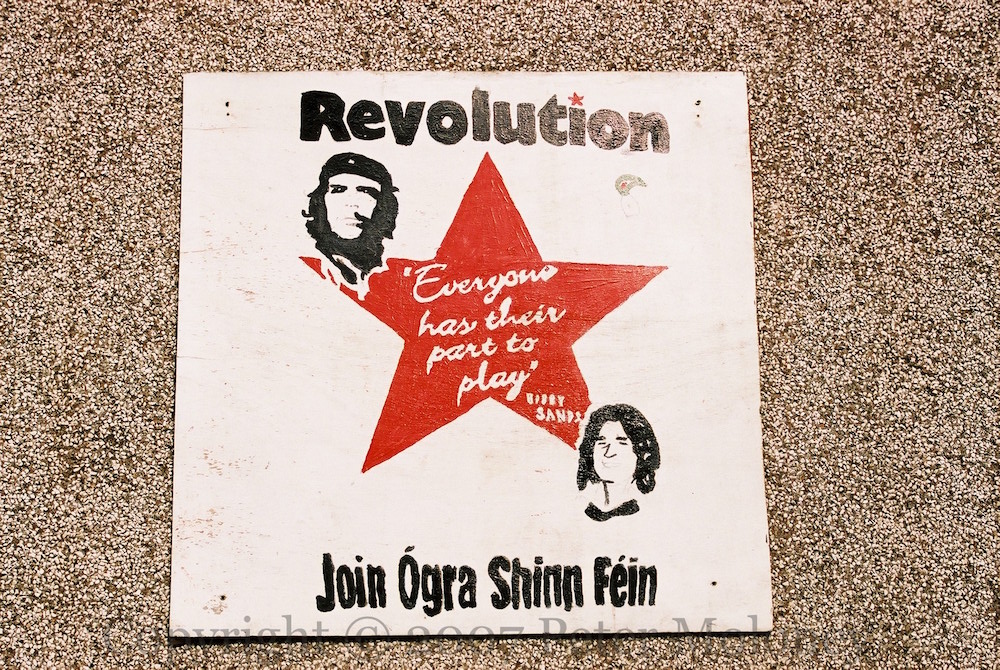

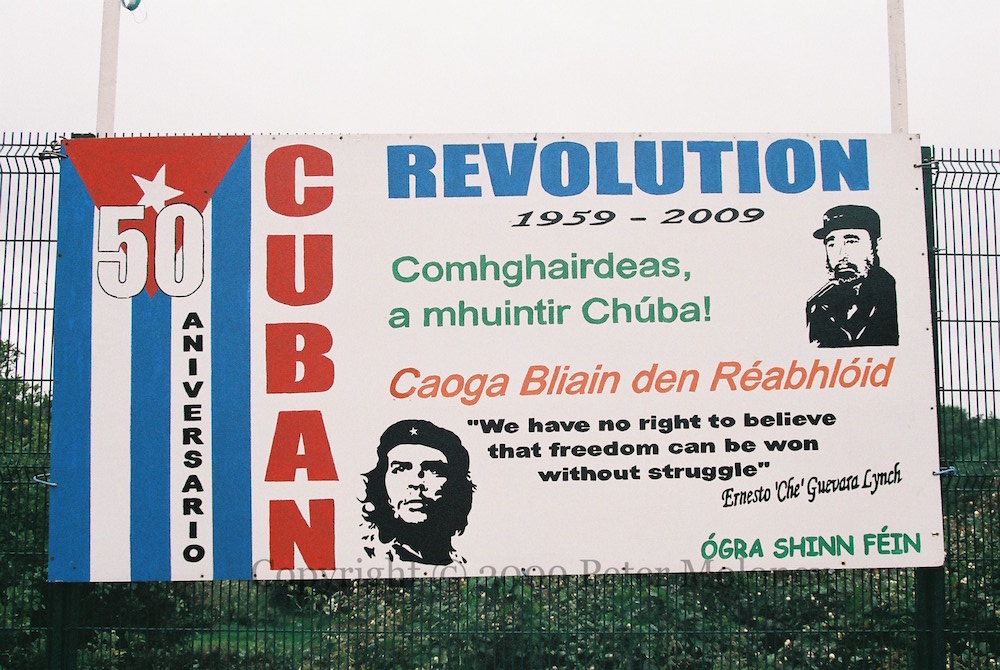

Ógra Shınn Féın/Sınn Féın Youth board in Omagh.

The long-running mural of Che in Fountain Street, Strabane, is replaced with Sands & Che.

Che is included in a gallery of socialist heroes: Seamus Costello, Gino Gallagher, Che, Patsy O’Hara, Miriam Daly, and James Connolly. Springfield Road, west Belfast, 2009.

Che and a raised fist in Barcroft Park, Newry.

Bobby Sands and Che together in Hugo Street, west Belfast, 2009.

County Antrim Gaelic games mural at Casement Park, west Belfast. The central figure is from Fitzpatrick’s ‘Hurling Match‘

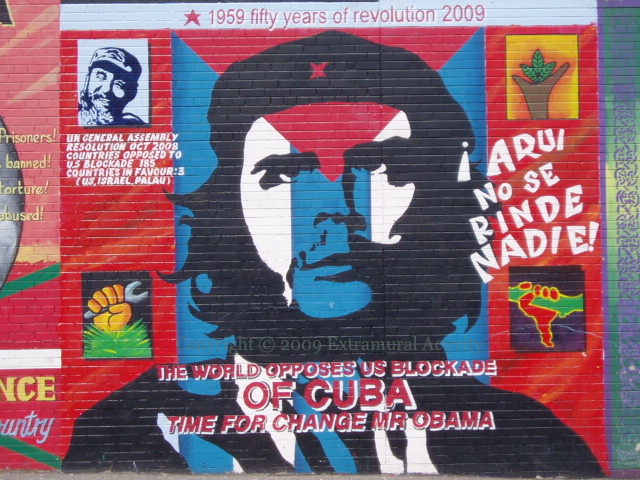

Che as the face of ’50 Years Of Revolution’ on the “International Wall”, Divis Street, west Belfast, 2009.

Che and Fidel as heroes of the Cuban Revolution in Strabane.

2009 mural in Kilwilkie, Lurgan, that reproduces Nuada The High King (which was used for the back and front covers of The Book Of Conquests).

Nuada Reborn by Mo Chara in an alley at the top of the Whiterock Road, west Belfast.

Fitzpatrick’s Nuada and Sadb along with Haverty’s Limerick Piper on the WBTA depot in King Street, Belfast city centre. Painted by a Short Stand artist and Marty Lyons.

Che says, “Vote for McCann” on the rear of Free Derry Corner. Artist unknown.

Niall And Macha. The Niall figure comes from Nemed The Great and the Macha figure from the Rosc label. Painted in Culdee, Armagh, by Belfast artists Lucas Quigley, Danny D, Marty Lyons, Micky Doherty, and Mark Ervine.

The main hurler from Fitzpatrick’s ‘Hurling Match‘ is part of a montage on the side of the bookie’s at the Falls Road-Whiterock Road junction.

Fitzpatrick’s Che x5 in McQuillan Street, west Belfast, by Damian Walker, with shields of (from left to right) the Basque Country, Palestine, Ireland, Cuba, Catalonia and ?Argentina or Guatemala?

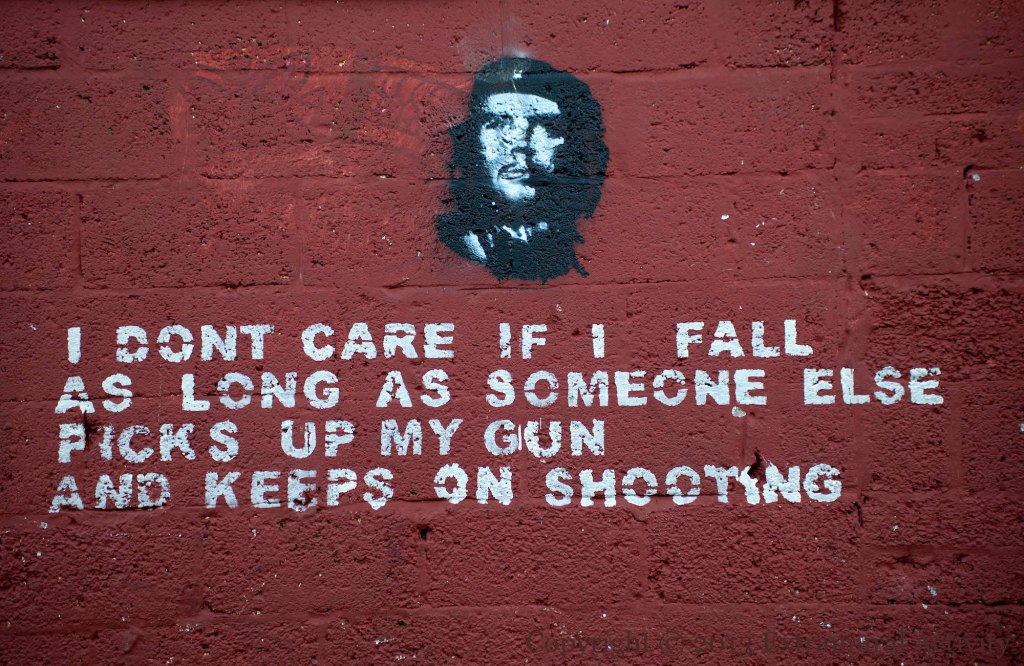

Che stencil in Westland Street, Derry

Che stencil and quote in St James’s, west Belfast.

A Che stencil in the New Lodge, north Belfast, 2014.

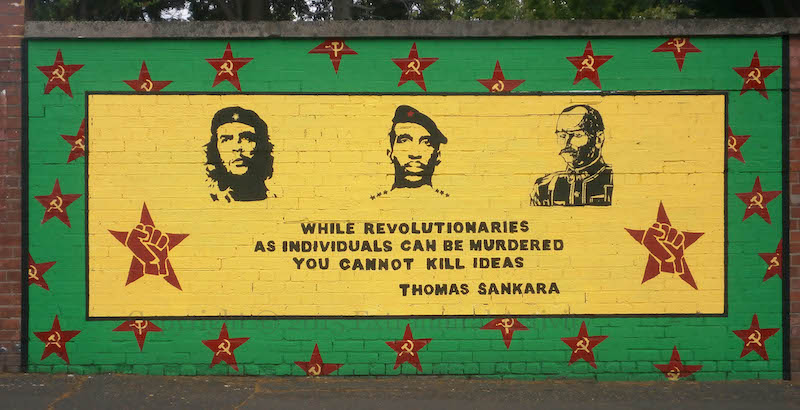

Viva Che! alongside Thomas Sankara (president of Burkina Faso) and Harry Kernoff’s wood-cut of James Connolly. Beechmount Avenue, west Belfast. Artist unknown. 2015.

Viva Che! on a small board in an alley between the Falls Road and Ross Road, west Belfast, 2016 or earlier.

Viva Che! did not appear in a CNR mural for a long time after the Sankara piece shown above, perhaps because the death of Fidel in November, 2016, took up the available attention to international socialism (see Hasta La Victoria Siempre and The Sun Of Your Bravery Laid Siege To Death). Che did return in La Solidaridad Invariable in 2021, though in a non-Heroico form.

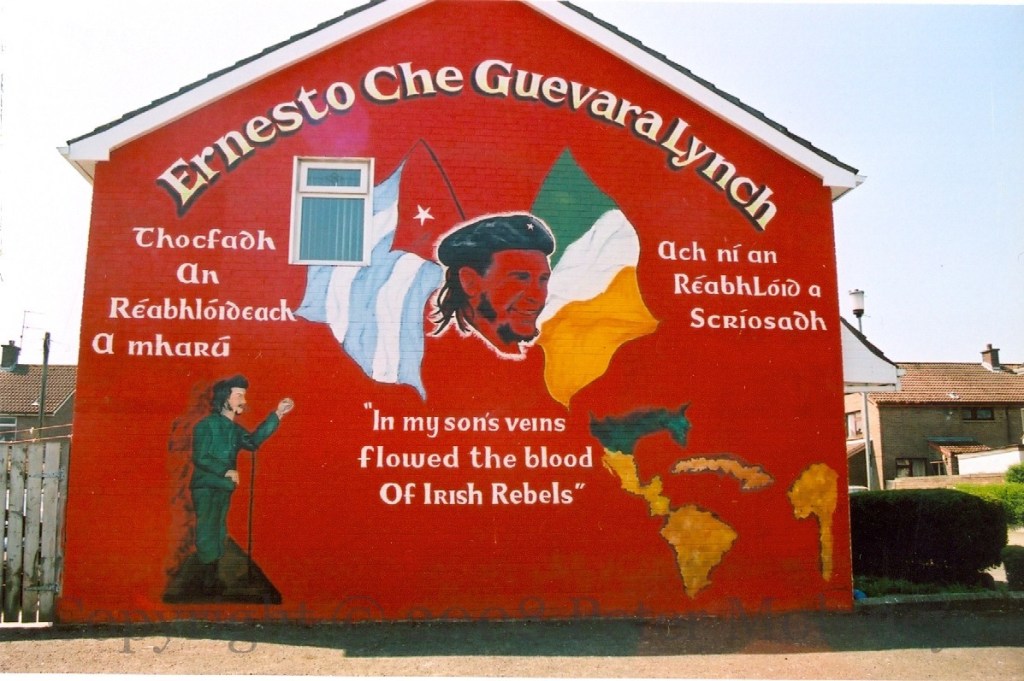

The most famous Che mural (because prominently placed and of long standing) is the 2007 mural in Fahan Street, Derry, celebrating his Irish ancestry. It does not use the Heroico/Viva Che! portrait. Rather, the source of this portrait is a photo of Che and Fidel Castro smiling – which can be seen in this BBC article. This mural continues to exist in 2024.

The repainted version of the Clann Lır/Children Of Lear mural in Cushendall included the harper from Fitzpatrick’s Lough Derravaragh.

Ard Eoın Kickhams, north Belfast.

Nuada Journeys To The Underworld as part of a mental health trio at Laurelglen pharmacy (off Stewartstown Road), west Belfast.

Che in the university district (Stranmillis Road), perhaps by a writer/graffiti artist.

The cover Fitzpatrick did for Thin Lizzy’s 1973 album ‘Vagabonds Of The Western World’ was reproduced in 2024 in east Belfast as a tribute to guitarist Eric Bell (the middle figure).

Che Heroico in Maghera

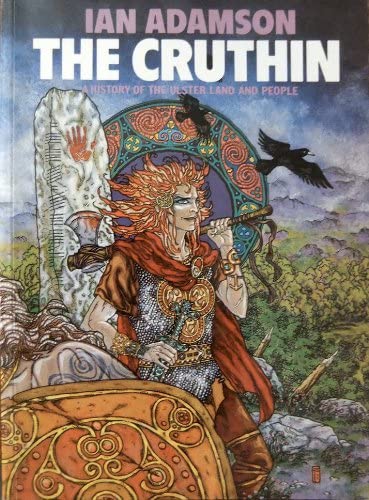

Fitzpatrick’s work has also appeared in the context of Ian Adamson’s ‘Cruthın’ hypothesis. (The Cruthın hypothesis is discussed on the Cú Chulaınn Visual History page.)

In 1980 – and so, predating any CNR use – Fitzpatrick’s vision of the battle of Moira (in 637) was used as the cover of Ian Adamson’s book The Battle Of Moira (Adamson’s blog post on the topic contains the image).

Much later – 2021 – this image was included in an Ulster-Scots board in north Belfast that also uses Oliver Sheppard’s Cú Chulaınn (and a Game Of Thrones character).

In 1984, Fitzpatrick’s ‘Cú Chulaınn, The Hound Of Ulster’ appeared on the cover of Adamson’s book The Cruthin. The full image can be seen on Fitzpatrick’s blog.

Key to reference numbers. Thanks to all of the following for the use of their images.

A = Alain Miossec Collection

M = Peter Moloney Collection – Murals

Bill Rolston

T = Paddy Duffy Collection

X = Seosamh Mac Coılle Collection

Written material copyright © 2024-2025 Extramural Activity. Images are copyright of their respective photographers.

Back to the index of Visual History pages.