Introduction (Click here or scroll down for Images | click here for the Appendix)

History

Pre-Troubles (pre-1969) murals in the Protestant/unionist/loyalist (PUL) tradition express the connection between Britain and Northern Ireland.

The greatest number of murals relate to the establishment of English Protestantism over the Catholic inhabitants of Ireland, the Williamite Wars, and two events in particular: the Siege Of Derry and (especially) the Battle Of The Boyne.

The siege began in December 1688. The recently deposed king of England (and Catholic) James II hoped to regain the throne using a mostly-loyal Ireland as a stronghold. His forces under MacDonnell attempted to secure the few remaining cities – including Derry – that were not loyal to him. When the ‘redshank’ army appeared outside Derry, thirteen apprentice boys on their own initiative grabbed the keys and secured the city (the “shutting of the gates”). When James himself appeared at the head of additional forces in April 1689, he was rebuffed with cries of “No surrender” and the siege continued. It lasted until July 1689, the “relief of Derry” coming with the “breaking of the boom” across the river Foyle by the ship Mountjoy.

James was ultimately driven out of Ireland by (Protestant) King William III, also known as “William Of Orange” and informally as “King Billy”. William arrived in Carrickfergus in June 1690 and marched south through Newry and into Drogheda where Jacobite forces were camped on the south side of the river Boyne. (Hence the classic image of the battle is King Billy on a horse reaching the south side of the Boyne.) James fled Ireland after the battle and the last of the Jacobites were defeated at Aughrim on July 12th, 1691 – which is the origin of “The Twelfth”, the annual celebration of the Protestant Ascendancy.

William’s victory was the end of a long transition period, beginning with Henry VIII in the 1530s, from Catholicism to Protestantism in the English crown. Catholicism had recently reared its head once again at English court after the restoration: in 1625, Charles I had married a Catholic (Henrietta Marie of France) and his son, James II, had converted to Catholicism and his second marriage was to a Catholic. (His daughter Mary, from the first marriage, was raised Protestant, and married William III in 1677.) After William & Mary, there would not be another Catholic monarch. This is the first (and typical) sense of the phrase “The Protestant Ascendancy” – the ascendancy of English, Anglican Protestantism in Ireland.

Although the Anglo-Normans had originally invaded Ireland (beginning in 1170) and the “union” is thought of as being between (Northern) Ireland and Britain, there is an even stronger connection between northern Protestants and Scotland, and therefore with Presbyterians rather than Anglicans.

By roughly 1720 Scottish Presbyterians had become the majority community in the province of Ulster, not so much by plantation as by economic migration, including a wave fleeing a famine in the Borders in the late 1690s. For the sake of comparison, consider the political map of Ireland from 1450 with one from 1816. In the first, we see the territories of the English king and the Anglo-Irish lords; in the second, (English) Protestant influence in the south is dwindling (Dublin county is shown to be at most 40% Protestant) while the counties that would become Northern Ireland range from 80% (Antrim) to 50% (Tyrone and Fermanagh) Protestant, much of it Scottish in origin.

Despite their great numbers in the north, Presbyterians were excluded from the Protestant elite, who were English in origin and belonged to the Anglican church. The founders of the United Irishmen, for example, were all Presbyterians, except for Tone and Russell, who were Anglican. The Orange Order, on the other hand, was founded in 1795 as a working-class organisation whose goal was the physical removal of, and defence against, county Armagh Catholics who had become equal in number to Protestants. With the defeat of the Irishmen and the relaxation of laws against both Presbyterians and Catholics, the “class war” between Protestants faded and the sectarian division between Protestants and Catholics became “ascendant”. This is the second sense of “The Protestant Ascendancy” – the ascendancy of Protestantism (of all denominations) in Ireland.

One hundred years after its creation, the Orange Order, which had by that time developed beyond its strictly working-class roots, became the focal point of resistance to the Irish Land League and the threat of “Home Rule”, that is, of either Irish self-government while remaining in the UK (“constitutional Home Rule”) or of complete separation (“revolutionary Home Rule” or “Fenianism”). The first Home Rule bill was debated in the Commons in 1886 and the second was defeated in the Lords in 1893. The third was passed in 1912, which prompted the Orange Order to organise the “Ulster Covenant” (September, 1912) in which almost half a million people swore to resist the Act. In January 1913, members for the new Ulster Volunteers were recruited from the male signatories. The Act, however, was postponed at the outbreak of the Great War.

Prior to the third bill, it seems, it was assumed that all nine counties would remain in the UK, based on the historical usage of “Ulster” and the other provincial titles in military and other Anglo-Irish structures. (Think, for example, of the 36th (Ulster) Division, the Connaught Rangers, and so on – “Ulster” in such cases referred to the nine counties.)

However, the idea of a six-county Northern Ireland was introduced in the third Home Rule bill (1912-1914) and a debate was held in the Lords as to whether partition would involve four, six, or nine counties; the eventual six-county separation is descended from a scheme of Lloyd George’s in 1916.

A Punch cartoon – dated 1913-10-08 – distinguishes between “SW Ulster” and “NE Ulster”, which might mean only the four counties with unionist majorities at the time. Redmond wonders if he should let the straining NE go and hope that it returns by itself.

Similarly, a 1920 cartoon shows “the Welsh wizard” David Lloyd George about to perform the magic trick of cutting away a nine-county Ulster, which will then somehow be reunited with the rest by stuffing the pieces into his “Irish Council” hat and waiting.

Some prints of the time show a UK comprising Britain and Ulster, for example, ‘The New Map’ at the National Museums Of Northern Ireland, and ‘Ulster’s Prayer – Don’t Let Go’ also from NMNI, and ‘Ulster’s Oath’ at Alamy HH4GRP. See also these articles from RTÉ’s ‘Century Ireland’ project: four options discussed | the 6-county partition plan is published | unionists in the three counties and the south react.

The fourth Home Rule bill was enacted in 1920. This stipulated two governments with limited powers in Ireland, one in the six north-eastern counties (Northern Ireland) and one in the other 26 (Southern Ireland), both still within the UK.

The fourth Home Rule bill separated only six counties from Southern Ireland rather than all nine Ulster counties. Although only six of the nine counties were included in Northern Ireland, unionists continued to think of the territory as “Ulster” and many organisations thereafter used the term “Ulster”, including the Royal Ulster Constabulary (and later the paramilitary groups the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Ulster Defence Association). “Ulster” is quicker and easier and more emphatic to say than “Northern Ireland”, in the same way that “Britain” is quicker and easier and more emphatic to say than “United Kingdom”. Thus it is possible, from a PUL perspective, to say “Ulster is British” in place of “Northern Ireland is part of the United Kingdom”.

After the War Of Independence, the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921 gave Ireland dominion status (akin to Canada) but Northern Ireland was given the option to leave (what was now to be called) the Irish Free State, which it immediately did, thus creating a 26-county Irish Free State and a six-county Northern Irish state that was within the UK but which had its own government with control over a variety of domestic policies. We are “carrying on a Protestant Government for a Protestant People,” said first prime minister James Craig in 1934 (NI Parliamentary Debates).

Muraling

As the Appendix at the end of this page makes clear, PUL muraling began in the early 1900s – prior to partition – and seems to have developed in response to the Home Rule threat (Kerr 1957 concurs) and as an extension of the arches, banners, and sashes on display during the annual celebration of the 12th. (Parades commemorating the Williamite campaign began to be held annually a century after Aughrim, in 1791, celebrating in particular the clash of kings at the Battle Of The Boyne, which had also taken place in July – July 1st in the Gregorian calendar or July 11th in the Julian calendar, introduced in 1752.)

Rolston (1991) notes that mass-produced paints (rather than paints made by painters themselves) became more readily available during this period and could be pilfered from the shipyard and other industrial sites (p. 20) and fell into the hands of one of the many able painters from the various painting trades, not just ship- and house-painters, but coach-, sign-, drum-, and banner-painters too.

Despite the skill that is evident in many of the paintings, early PUL murals are not included in surveys of British murals. There is from the beginning something about them that seems to alienate the art establishment. There are various possible reasons for this: one is that the painters are not professional artists, such as were Frank Brangwyn or Barbara Jones (or Belfast’s own John Luke – see his Charter Of Belfast in the city hall); another is that being in working-class areas means these are art for working class people; another is that being in the street rather than a gallery means their life-span is short; another is that being in the street rather than in a church or civic building means that these murals do not have ready norms for interpretation (see e.g. Brian O’Doherty Inside The White Cube who compares the norms for being in a gallery space with “other spaces where conventions are preserved through the repetition of a closed system of values. Some of the sanctity of the church, the formality of the courtroom, the mystique of the experimental laboratory joins with chic design to produce [in the gallery] a unique chamber of esthetics.” pp. 14-5).

A final possibility, and perhaps the most important, is that, while on the face of it the murals deal with the same sorts of regal and heroic themes as “fine-art” murals, the early PUL murals adopt these themes not just for exalting and reinforcing the status quo (including personal elevation towards the (state-sanctioned) understanding of the divine, as in ecclesiastical murals) but also for the purposes of protesting the proposed abandonment of Ireland by Britain and of establishing themselves over the minority community in the north of Ireland. In other words, a King William painting in England is different from that same King William painting in the north/Northern Ireland, just because of the differing political contexts. Less clear is whether something like Luke’s Charter Of Belfast (1951), which was painted in Belfast City Hall, would be perceived differently had it been painted instead on a Shankill gable wall.

With the creation of the Northern Irish state, the anxieties of Home Rule were lifted and one of the two purposes mentioned – fear of abandonment – becomes more difficult (though not impossible) to perceive, leaving as the main explanation for muraling the consolidation and perhaps even the “triumphalism” of the Orange state over the 420,000 Catholics who now formed the minority community. Loftus and Rolston disagree on the question of whether the early PUL murals are “oppositional” towards the Catholic community. Loftus (1982) considers the locations of the murals and in a survey of some of the painters themselves they profess no enmity towards Catholics; she wisely notes, however, that this is just what journalists and researchers from the outside might expect to be told. It is also possible that the murals reinforce in the minds of Protestants Protestant superiority over the CNR community (that is, whether or not Catholics see the murals). Rolston for his part writes that “the ritualistic parading of unionist symbols is and was inevitably triumphalist … and part of the annual ritual was the painting and repainting of murals” (1991 p. 18, 20). (Here is a 1922 newspaper report in The (Melbourne) Advocate of the anti-Pope slogans painted alongside “crudely painted” King William murals. “Still, the painting on the dead walls and gables of the Orange quarters engrossed the time and talents of many, and offered safety valves for fiery-minded “lodge” men as they took care to finish the decorations with sulphurous oaths and scurrilous blasphemies.”)

Compare such worries about the sectarian impact of murals with this statement by Clare Willsdon in her Mural Painting In Britain 1840-1940: Image And Meaning: “[The muraling of this period] was felt in its time to be a kind of art extraordinaire, making painters into heroes, viewers into visionaries, and buildings into architecture. Mural painting lent authority, imbued respect, revealed religion, and fostered faith. Thoughts, dreams, and ideals might be given vivid presence in hall or home alike, and artistic genius unleashed. Present could be joined with future, time with place, and man with fellow man. In public buildings, churches, or schools, murals might offer a focus for ritual and remembrance. … Sir Patrick Geddes … demanded “Instead of this endless labour on little panels [that] flap idly upon rich men’s walls, … make [the muralist] work for hall or school, for street or square” … A reviewer wrote that “The mural painter is not only a painter, but a poet, historian, dramatist, philosopher.” (p. 3) If a mural’s glorying in either the state or the state’s religion must be for the sake of uplifting the viewer in accordance with the status quo, it becomes explicable (if not excusable) as to why not a single PUL street mural is included in Willsdon’s survey.

Cooper & Sargent’s 1979 picture book Painting The Town is focused on the civic wall-paintings undertaken by various institutions (borough councils, schools, Job Creation schemes, etc) in England, Wales, and Scotland from 1972 onwards as attempts to “brighten the environment” but it does make mention of early PUL murals in its brief history of muraling: “It is believed that the central European custom of exterior painting inspired the political folklore murals that were painted in Northern Ireland from the reign of William of Orange.” (No source is given for the claim about the influence of European muraling or the claim that the murals began around the time of William III.) Five murals from the north are included among the pictures, including two of Bobby Jackson’s murals in the Fountain. (Images of both appear below.) These might have been expected to appear at the start of the book but perhaps were moved later because they don’t quite fit the book’s main theme. The Jackson murals are joined by the King Billy in “Donegal [sic] Road, Belfast” (i.e. the King Billy in Rockland Street – see below). Fourth – and fitting squarely into the main theme of the book – is the ‘Brief Encounter’ (more familiarly called the ‘French Letter’) painting on the Mourne Bar in the old Derry city. And finally there is one from “Londonderry’s Bogside”, showing an IRA volunteer standing above an Irish Tricolour with “Easter 1916” in the middle and next to what the authors describe as a “torch signifying [along with the Tricolour] that the spirit of the 1916 uprising is still alive” – this “torch” is, in fact, an Easter lily (see Visual History 02).

Images

This page presents a few examples of early PUL graffiti and murals; links to many others can be found in its Appendix, which attempts a list of all early PUL murals (up to 1980). (“Unionist” might be a better term for these murals, if “loyalist” is reserved for paramilitary murals. For simplicity, we generally use “PUL” throughout these pages.)

Murals celebrating the Williamite campaign are the most common in early PUL muraling (and continue to be painted during the Troubles, as later pages will illustrate). The most common image is of King William on a horse at the Boyne, particularly as portrayed in Benjamin West’s painting The Battle Of The Boyne – Belinda Loftus (1982 pp. 45-105) spends a chapter tracking the spread and significance of this particular image throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Here is a 1909 newspaper article (in the Watchman) about the proliferation of post-cards (and even Christmas cards) portraying King William III.

Neil Jarman (1995 p. 115) writes that images of Unionist leaders Edward Carson and James Craig were seen in murals after partition.

There was other imagery expressing identity with, and loyalty to, Britain and the Empire. Loftus (1982 p. 61) gives a list of some of the other subjects of early loyalist murals, as follows: “The ship named “Mountjoy” was shown breaking the boom …; Lord Roberts appeared flanked by two Boer War soldiers; the Ulster Division went over the top at the Battle of the Somme …; the Angel of Mons hovered over the battlefield; the “Titanic” …; King George and Queen Mary …; the visit of the Prince of Wales …; Victory was celebrated in 1945 with rising sun and fly past of aeroplanes”. In particular, there seem to have been many murals painted c. 1935 and 1937 for the silver jubilee of George V and the coronation of George VI, respectively.

In terms of symbols (rather than scenes or portraits) we see the crown, the Bible (and other Orange symbols), and depictions of the flags of the UK and of Scotland, as well as the symbol of the new Northern Irish state, the Ulster banner. We also see historically Irish symbols such as the harp and the shamrock which had been adopted by the English in Ireland.

Home-Rule-Era Muraling

This Bobby Jackson mural of The Landing Of King William III At Carrickfergus dates back possibly as far as 1916. Lacking the dramatic context and activity of the Battle Of The Boyne painting, this is the only mural of this scene, as far as we know. (Loftus 1982 p. 62 concurs.)

1920: “No surrender. IRA [Irish Republican Army] name your day – the B Men are ready.” The “B Men” were the ‘B Specials’, the Ulster Special Constabulary, a reserve force. The B Specials were established in October 1920, before partition. They existed until 1970 when they were replaced by the UDR.

There was also graffiti in Derry in ?1920? reading “Derry says No Surre[nder] – Brittannia [sic] Rule[s] …” (British Pathé); still image available at Alamy.

The most famous King Billy is the “Jackson Mural” in the Fountain, Londonderry, by Bobby Jackson Senior and Junior. King Billy at the Boyne is on the left and the Siege Of Derry on the right. The mural originally dates to the 1920s (Rolston 1991 p. 24 and 1992 p. i) or 1940s (Woods 1995 p. 11).

There is a separate Visual History page for the Bobby Jackson mural in the Fountain area of Londonderry, with images dating to the 1970s.

The “Rockland Street” or “Village” King Billy dates back to roughly 1932. It was touched up frequently and repainted on several occasions. The earliest image available if is of the 1954 repainting. Kerr 1957 (p. 15) reports that the mural had been repainted in 1954 by a Mr Beattie who lived in the street; the Lord Mayor came to unveil it. Beattie followed the previous design but Kerr attributes the textured sky in particular to Beattie. A photograph of the mural appears in her book; the following photograph is from Loftus 1983, taken in the early 1960s.

The mural shows King Billy crossing the Boyne within an arch; above are crossed Union Flags; to the left and right are shields atop columns of Orange symbols. These elements and framing would be preserved throughout the decades, though sometimes the mural was repaired by simply painting over parts of it. There is a separate Visual History page for the Rockland Street King Billy.

Heyday And Decline

Little can be inferred with confidence about the ebb and flow of PUL muraling as the record is thin throughout. But the hypothetical timeline seems to be something like this:

(a) that the 1930s were a heyday for PUL murals, with some walls being replaced or repainted (not just touched up) very frequently;

(b) that muraling took a down-turn during and after WWII.

In support of (a):

Kerr’s 1957 description of the Clifford St murals is worth quoting at length, as it illustrates the frequency with which murals had been painted:

“The first impression one gets is of the rain washed colour of these paintings, which is white, soft blue, pink and yellow on a dark background. … The white cenotaph has “IN GLORIOUS MEMORY” written on it … Around the circle are various indistinct flags, and 1914–1918 is written on either side of a crown and Bible at the very top. Crossed jacks are on either side of the circle, and underneath these are shields at about eye level with names in them, “FAITHFULL UNTO DEATH” underneath, and plumes with French, British, Belgian and American flags on top. Across the top of the whole wall at roof level there is a great orange frill which looks as if it was part of an earlier painting.

“There have been several paintings on the yard wall beside the cenotaph. There is an orange arch square in shape with its base on the pavement with the title “THE MOUNTJOY BREAKING THE BOOM” written across the top. … On the river a brown and black out-lined sailing ship can still be seen. … Even this [the King Billy] has been painted several times as the horse has three back legs in various positions.”)

Although Kerr is writing in 1957, it is more likely that the changes being reported go back to the 1930s. At least, there are photographs of the wall with different murals in 1934 (see link in appendix) and ?1935? (see above).

Similarly, note Wilgaus’s activity in Snugville Street: in 1935, a George V coronation mural; in 1938 George VI and family.

In support of (b):

The Rockland Street King Billy is one of the few that Kerr 1957 finds in her survey of that year. Jarman (1995 p. 117) writes similarly that “In 1960 their [the Belfast Newsletter’s] reporter found only one painting in good condition in Belfast, a King Billy mural in Silvergrove Street first painted in 1938 and redone in 1960 (see photo BNL 9-7-1960)”; others in east Belfast, the Ormeau Road and Shankill areas were “so faded that only the poorest outline was visible” (BNL 12-7-1968)”.

The Appendix below lists only a few murals from the 1940s and 50s, though murals painted in the 1930s seem to have survived. Two murals in the Appendix, of George V’s silver jubilee and George VI’s coronation, both seem to have lasted a long time. The George V mural, which we guess was painted ~1935, survived into the 1960s – at least 25 years; the George VI mural painted ~1937 survived at least until it was photographed ~1969 by Reader – 30 years and more. Both were likely touched up periodically but not, it seems, replaced.

Causes of the decline might include: the absence of the threat of Home Rule; the successful subjugation of the Catholic population (see Visual History 02); the shift in focus (and rationing of goods and materials) made necessary by WWII.

As the Troubles began, PUL muraling revived to some extent; but the skilled painters of the pre-war era had stopped painting and murals were revived by painters with a range of skills who attempted Williamite imagery but also leaned more heavily on flags and symbols. These trends are considered in the next section.

Early Troubles-Era Graffiti & Muraling (to 1981)

In the wake of rioting in Derry in August and October 1968, UUP leader and NI prime minister Terence O’Neill introduced a five-point reform plan which was perceived as too generous by hard-line Protestants and as insufficient by young Catholics, who in response formed the People’s Democracy (PD). After a PD march from Belfast to Derry was attacked at Burntollet without police intervention in January 1969, O’Neill called a snap election, causing a split in the UUP. Ian Paisley ran against O’Neill in Bannside. (Here is Pathé video of Paisley leading an anti-O’Neill protest.) O’Neill won his own seat narrowly but overall he and his supporters controlled only 26 of the 52 seats. After UVF attacks on water and electricity infrastructure in April (Balaclava Street), O’Neill resigned.

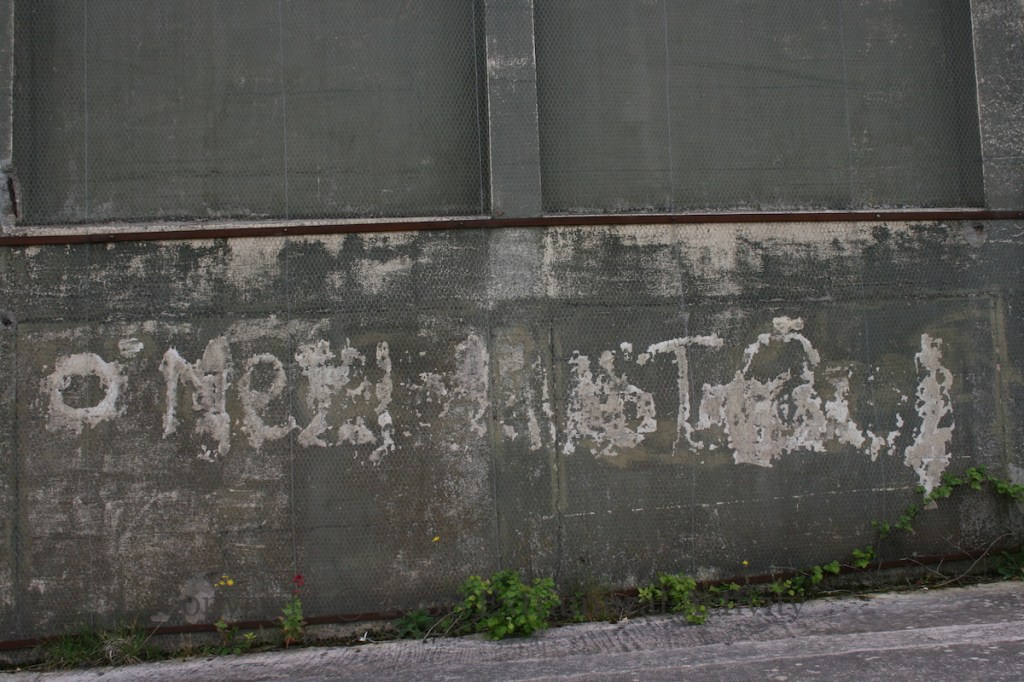

This graffiti – “O’Neill must go” – is on the British Portland Cement building outside Magheramorne, possibly dating to 1969 or before.

(A few other examples of graffiti supporting Paisley: Getty 50675200 “God save Paisley” 1966; Getty 647608182 1966; X02530 “God bless Paisley – Fitt never” 1969?; “We are the people” “Paisley” David Lewis 1969; Alamy A7N93B showing “REM 1690” “UVF” “Ulster not for sale” and “Paisley forever” 1970s; Getty 75884216 1972)

“No surrender”, “God save our queen”, and “Shankill rule OK” in Hopewell Street. (Fribbler on WP | X09162)

The beginning of what are called “The Troubles” is usually given as the summer of 1969, when serious rioting took place in Derry (The Battle Of The Bogside) and Belfast, in response to which the British Army was brought in to help the RUC [Royal Ulster Constabulary] maintain order. (See Visual History 02 for more information about the years following from the CNR perspective, including internment and Bloody Sunday.)

The urgency of the times gave rise to urgently-written graffiti on the walls and on barriers erected to separate Catholics and Protestants in parts of west Belfast. Getty 515284714 shows (PUL) graffiti on corrugated iron barrier erected during the rioting of 1969, reading “No surrender”, “Taigs [Catholics] beware”, “REM 1690”, “No pope here”, “One faith, one crown” and behind the barricade Union flags and banners reading “We shall never forsake the blue skies of freedom for the grey mists of an Irish republic” and “For Ulster there can be only one form[…obscured…] that [is] a spiritual unity of freedom.”

(For more about the early history of the west Belfast “peace” line, see State Art Vs Graffiti On The West Belfast “Peace” Line.)

During the early period of the Troubles — from 1969 to the hunger strikes in 1981 — Williamite murals are painted, though many of them are very crude and it is not clear that we can say that the tradition has continued unbroken. It appears that by the era of Civil Rights and the Troubles, the skilled painters of the first half of the century – who in many cases worked in painting trades – were aging out and the tradition had not found new practitioners of the same calibre. The next few images show King Billy murals from the 1960s and 70s that are generally smaller and much cruder than those shown to this point.

A few of the more ambitious pieces are shown here; the Appendix includes other PUL pieces from the early years of the Troubles. (CNR pieces from the 70s are collected in Visual History 02.)

‘King Billy Crossing The Boyne’ mural in Victoria Street, Londonderry. Around the arch are the words “In god our trust” and the shield of Londonderry.

King Billy at the Boyne, with the crown and Bible on a Union flag, above. Park Street, Coleraine.

Orange symbols and King Billy on a horse in Larne

“Traditional” murals were joined in this period by murals using (only) flags and emblems, such as of the Northern Irish state and the Union Flag. These still express the Britishness of Northern Ireland, but do so in perhaps a more direct fashion than do images of King Billy. It is possible that the armed violence changed the climate such that large and/or intricate murals became more difficult to envisage and the symbols of unionism became more popular for both practical and psychological reasons. Some murals – but not many – were explicitly connected to PUL paramilitary groups such as the UVF and UDA.

There are not many of these murals from this period and only a few such murals appear in mural collections – please see the Appendix below for references. We end this page with images of four murals at the entrance to the Waterside, Londonderry, two on either side of Bond’s Street. First, the eastern side, in Bond’s Place. On the lower side, the Ulster Banner in shield form is surrounded by Union flags; on the upper side, “1688-1690 Ulster”. The six-pointed star at the centre of the Ulster Banner (and often used by itself, as in the second image of the two) represents the six counties of Northern Ireland.

On the other side of Bond’s Street, there were also two murals facing one another in Ebrington Terrace.

First, the flags of Canada and Australia are included on the southern side. (This is the wall that in later years would be the site of a series of ‘Eddie The Trooper‘ murals.)

To the right of these two commonwealth flags are Orange Order and Apprentice Boys flags; these are two of the three main PUL fraternal organisations, along with the Royal Black Institution.

The northern wall shows the St Andrew’s Saltire, the Ulster Banner, and (smaller) the Union flag.

A wider range of PUL images was painted inside the UVF compounds of Long Kesh during the mid- to late-1970s. The appendix of Hinson 2017 lists 47 murals and contains images of 44 of them. (Eight can be seen on Bill Rolston’s page on prison murals.) As expected, there are paramilitary emblems and commemorations (though no weapons or volunteers in active poses) in a quarter (12/47) of the murals, and a few (3) on the UVF’s pre-history in Carson and the gun-running. There are also a few (3) showing Northern Ireland and its emblems. But 14 of the 47 are on the British military and military history, especially WWI – anticipating a theme that would find favour much later in PUL muraling (see Visual History 08 which covers 1996-2001. (One of these showed a figure split down the middle, with WWI soldier on the left and modern volunteer on the right; Billy Hutchinson picked out this mural for particular attention in his essay ‘Transcendental Art’. A similar idea would be used in a 1986 mural in Craven St – see M00560.) Most surprisingly for the time, 14 of the 47 are “scenic”, showing beauty spots from around the country (and one of Belfast City Hall).

An ex-prisoner who painted five of the boards explained (in an interview with Extramural Activity) that the first mural was perhaps a mural with all of the 36th Division infantry battalion badges, based on an image that Gusty Spence had. Once the prisoners saw this one, the idea spread to having one for each cell until “every wall was covered”. This would have been 1975, though muraling began in earnest only when the compounds became more permanently allocated to different organisations (from January 1976 onwards). The variety was due to “Gusty making you think a little bit wider … You did not have to flaunt the organisation – you were living it 24/7; there was no need to be reminded of the balaclavas and the guns … so [the muraling] was very much more culture-driven and historical.” According to Hinson 2017, the muraling ended in 1981.

On to Visual History 02 – The Catholic Insurgency …

References in parentheses to mural collections:

M = Peter Moloney Collection – Murals

X = Seosamh Mac Coılle Collection

Appendix

This page (and the next) gathers together all of the references to early murals. PUL murals are listed on this page. If you know of, or have images of, additional murals (or graffiti), please e-mail extramuralactivity@gmail.com. Dates in the list below should generally be understood as ‘floruit’ rather than precise dates of creation.

- 1908 According to Loftus, “The first documented example [of PUL wall-painting] was a King Billy mural painted by shipyard-worker John McClean in Belfast’s Beersbridge Road in 1908.” (Loftus 1983 p. 11. Loftus 1982 p. 57 gives as the source a 1958 article in Ireland’s Saturday Night that we have not yet been able to access.)

Possibly in Clara Street – see the next entry.

Tommy Henderson from the Shankill also claims that he painted the first mural, but gives 1912 as the date (Kerr 1957 p. 13).

Both the 1908 mural in this entry and the two 1911 murals in the next entry are in east Belfast and so Henderson is probably wrong about his claim. - 1911 “The usual arch at Albertbridge Road, on Malcolm Street, has been replaced by a large painting of King William on the side of a house at the corner of Malcolm Street. The painting has been draped with purple, garlanded with evergreen and surmounted by loyal and patriotic mottoes, Union Jacks, portraits of the King and Queen and Orange leaders, and, above all, the inscription “God Save the King”. A somewhat similar idea has been effectively carried out on the gable of a house on Beersbridge Road near Clara Street.” July 12th, 1911 Belfast Telegraph article quoted in Jarman 1995 p. 112

- 1912 “We Won’t Have Home Rule” (Edith St, Belfast) King Billy below a trio of portraits with Carson in the centre (X05591) (Possibly the Tommy Henderson mural mentioned in the 1908 note, above, but this has not been confirmed.)

- 1913 King Billy Crossing The Boyne (Dee St, Belfast) in Rolston 1991 p. 22

- 1916 The Landing Of King William III At Carrickfergus (Londonderry) (see above)

- 1920 “No surrender. IRA name your day – the B Men are ready.” (Londonderry) (see above)

- 1920 “Derry says No Surrender – Brittannia [sic] rule[s]”

- “Sir Edward Carson was also portrayed on at least one wall (NW 13-7-1914)” Jarman 1995 p. 112. (Possibly X00094 “Carson Portrait On Gable” in Carnan Street, being painted by Tommy Henderson.)

- “At Hornby Street the painting depicted the “Mountjoy breaking the Boom” overlooked by an imperial Britannia” Jarman 1995 p. 114

- “At Victoria Street [Londonderry] the painting of King Billy was surmounted by an Ulster Red Hand symbol” Jarman 1995 p. 114 (see Cooper 2015 p. 105 for King Billy alone)

- “At Carnan Street it took the form of a memorial to those killed in the war, the Red Hand and Union Jack flags flew over a mourning figure and underneath the memorial was the motto “For King and Country”” Jarman 1995 pp. 114-5

- 1920s King Billy Crossing The Boyne (possibly Henry St, Belfast) (The BFI film The Agony Of Belfast)

- 1920s King Billy Crossing The Boyne (Rockland St, Belfast) mentioned in Rolston 1991 p. 24 (possibly the same as the later Rockland St Billy – see 1932)

- 1920s or 1940s King Billy/Siege Of Derry “The Jackson mural” (Fountain, Londonderry) (see above)

- ?1922? A British Pathé newsreel of Michael Collins electioneering in Co. Cork in 1922 contains some stray scenes, including one of a mural being painted on a gable in Belfast. It is possibly of the mural that Loftus above described as “Lord Roberts … flanked by two Boer War soldiers”. There appears to be a city in top left and Union Flag in the top right; two soldiers stand on either side of an armless bust (here are two such of Roberts one | two) on a pedestal with a female figure laying a wreath at its base. Please get in touch if you can identify the subject definitively.

- 1922 A mural to the recently-assassinated Henry Wilson, with Britannia to the left and a saluting soldier and words from Kipling’s ‘Recessional’ to the right (C08877). Limestone Road, Belfast. See also 1926, below.

- 1922 Portrait of Henry Wilson in Pittsburg Street, Belfast (C08876).

- 1923 “On Primitive Street the mural included the figures of a soldier and a sailor and the names of some 50 local men who had been killed. It was ceremoniously unveiled by Harry Burns MP on the eleventh evening (BT 12- 7-1923)” Jarman 1995 p. 115

- 1926 “On Dundee Street a crowd of “several thousands” attended when a new mural was unveiled by Sir Robert Lynd MP. This mural was painted over four evenings by a local sign writer, George Wilgaus, and depicted the battle of the Somme and a portrait of General Sir Henry Wilson, the Unionist chief of the Imperial general staff (NW 12-7-1926).” Jarman 1995 p. 115.

- 1929 Nurse [Edith] Cavell in Primitive Street, Belfast. Images in Rolston 1991 p. 21 and C08878.

- 1930s King Billy (wearing a ‘turban’) Clarence Place, Londonderry. (Woods 1995 p. 10 | Cooper 2015 p. 15)

- 1930s “In glorious memory of William Prince Of Orange” by “T Henderson, drum maker and painter”, in the Shankill (Rolston 1991 p. 22 | Linen Hall Library | X05908)

- ?1930s? (fl. 1957) King Billy on a rearing horse (Henryville St, Belfast) by Steeny Biggart. Kerr 1957 reports that this mural was extant in 1957 but that her father remembered it from his younger years. Kerr describes the mural on p. 18 and provides a watercolour painting of it on p. 20 (which is also used on the front cover) and a line drawing of it on p. 16.

- ?1930s? (fl. 1957) Cenotaph (Rathmore St, Belfast), illustrated with a line-drawing on p. 17 of Kerr 1957

- 1930s King Billy Crossing The Boyne (Shankill Rd, Belfast) (Rolston 1991 p. 22)

- 1932 King Billy (Rockland St, Belfast) (see the separate Visual History page)

- 1933/1937 King Billy Crossing The Boyne (Templemore St, Belfast) in Rolston 1991 p. 23 and Crowley 2022 p. 90 and C08890 (C gives 1937 as the year).

- 1933 36th (Ulster) Division emblem “In remembrance of the officers, NCOs & men of the 36th Ulster” by John McIlroy (Fortingale St, Belfast) in Rolston 1991 p. 21 (also mentioned in Loftus 1982 p. 59 | also C08879)

- 1933 King Billy Crossing The Boyne (Roslyn St, Belfast) in Rolston 1991 p. 22 and C08888.

- 1933 King Billy Crossing The Boyne (Louisa St, Belfast) C08888.

- 1934 King Billy Crossing The Boyne (Maria St/Pl, Belfast) (in Rolston 1991 p. 23)

- 1934 King Billy with Prince Of Wales and Carson (Maria Pl, Belfast) (C08886 | X09158)

- 1934 Cenotaph with King Billy and Orange symbols + Relief Of Derry (Clifford St, Belfast) (C08880 | X05555). See also 1935 Clifford St, below. A photograph of these murals painted over but still dimly visible appears on p. 22 of Kerr’s Glorious Twelfth.

- 1935 Battle Of The Somme (Coolfin St, Belfast) in Rolston 1991 p. 21 (C08881)

- 1935 “Lest We Forget” (Clifford St, Belfast) cenotaph + King Billy side-wall. Kerr 1957 suggests 1918 as the date of creation of the cenotaph mural but this seems likely to be simply the end-date of the War, especially given the frequent repainting – see 1934 Clifford St.

- 1935 Silver jubilee mural depicting the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911 (Snugville St, Belfast) by George Wilgaus. (C08882)

- 1935 Silver jubilee mural depicting the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911 (Little Ship St, Belfast), in Loftus 1982 p. 59 (see the end of the entry on the 1937 King George VI mural, with which this mural seems to have been confused)

- 1936 King Billy Crossing The Boyne (Tierney St, Belfast) by Howard Kelly and Fred Crone (C08889). See also 1939 Tierney St.

- 1937 Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1937 (Little Ship St, Belfast).

The Getty archivist, alongside the image by Bert Hardy in 1955 (Getty 3375213 | X09166), incorrectly says that this mural is of the coronation of Elizabeth II and Prince Philip!

Christopher South in the Sunday Times magazine of 1969-03-23 correctly gives “George VI and his Queen” in his notes accompanying John Reader’s photograph of the mural. Here is the spread from the magazine which includes Reader’s image (X05644).

Loftus 1982 p. 59 describes a mural of “George VI and Queen Elizabeth” painted in “1938 or thereabouts” in “Marne St”. This is probably the mural under discussion: “Marne St” should be “Marine St” which is the street next to the mural, on Little Ship St. There is no “Marne St” in Belfast in directories from 1932 or 1939 (Lennon-Wylie).

C08883 gives the News Letter’s image of this mural.

The 1935 and 1937 Marine Street murals are sometimes confused.

Loftus 1983 p. 14 presents an image from the 1960s (regrettably of poor quality, at least as reproduced in the 1983 magazine) of what she describes as a jubilee mural for George V. Loftus’s description (1982p. 61) is then quoted by Rolston (1991 p. 20), but the text is accompanied by an image of the 1937 George VI mural. The confusion is perhaps due to the fact that the general description fits both murals – king and queen in regalia, in front of chairs, with drapes as a frame, etc. But there are a few substantial differences, in particular the width of the drapes-as-border, which rule out their identity.

It is not known whether the 1935 mural was painted over for the 1937 mural or they were on different walls. - 1938 King Billy Crossing The Boyne, Silvergrove St, by Harold Gibson

- 1938 George VI, Queen Elizabeth, Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret (Snugville St, Belfast) by George Wilgaus (C08884 in progress)

- 1939 (repainted version of 1936) King Billy Crossing The Boyne, Tierney St by Howard Kelly and Fred Crone (pictured in Rolston 1991 p. 22)

- 1939 King Billy Crossing The Boyne, Earl Lane (in Rolston 1991 p. 23 “In 1939 in Earl Lane, a mural obviously based on the same source as the Maria Place painting had added to it a frieze and the names of men killed during the sectarian riots in the area four years previously; “Their only crime was loyalty” noted the mural artist (see Belfast Telegraph, 7 July 1939, p. 20.”) See C08887.

- 1940s God Bless Our King And Queen, Woodvale Rd, by George Wilgaus

- ?1940s? King Billy, Empress Street (Kerr 1957 p. 21)

- 1940s Dieu Et Mon Droit, ?Crimea St? at junction with Upper Charleville St

- 1941 fl. Hold Fast, Ulstermen. (unknown location) The texts in the apex read: “We honour them. They knew no fear. Closed the gates to maintain our cause so dear.” and “Hold fast, Ulstermen. The north’s your ground. ‘Twas proved at Derry and the Boyne.” The illustration is (therefore) of the siege of Derry. Carson’s name is in the first arch and a portrait of William III is in the second. X15790

- ?1950s? King Billy, Wauchope St (Kerr 1957 p. 21)

- 1955 Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip, Malvern St, Belfast (Newsletter of 1955-07-08 | mentioned in Rolston 1991 p. 28. The Queen Elizabeth possibly shown in Alamy AE6DB9 or Alamy EEANKE)

- 1957 fl. King Billy in Dromara St (Kerr 1957 p. 16)

- 1958 Colonel Murray, Clarence Pl, Londonderry, by Bobby Jackson (C08892)

- 1960 repainting of 1938 King Billy Crossing The Boyne, Silvergrove St. (Image from 1963 in Rolston 1991 p. 26)

- 1961 Jubilee mural of the coronation of George V & Mary (Loftus 1983 p. 14)

- 1964 “an incredibly amateur painting of King Billy at Northumberland Street” Sunday Press 1964-01-26 (quoted in Rolston 1991 p. 26)

- 1965 repainted King Billy Crossing The Boyne, Earl Ln, Belfast. (King Billy on horse, in a circle with the seven names of victims of 1935 and “Their only crime was loyalty” – much simplified compared to 1939 version). Sponsored by Fleet Street Band, with speech by Ian Paisley at the launch. (b&w image of Paisley speaking in Rolston 1991 p. 27 and C08893 | colour image of mural at Alamy AK348G | mentioned in Loftus 1982 p. 59)

- 1965 King Billy Crossing The Boyne, Eighth St, Belfast (Rolston 1991 p. 28 | Howard – Alamy AK32CM)

- 1967 King Billy Crossing The Boyne, Hudson Pl, Belfast, (Rolston 1991 p. 28)

- 1969 “Faith, Hope, Charity” various Orange symbols, Larne (see above)

- 1969? “God bless Paisley – Fitt never” Gardiner St, Belfast (X02530)

- 1970 King Billy, Albany St, Belfast (X05539)

- 1970 King Billy Crossing The Boyne, Rosewood St, Belfast, (Rolston 1991 p. 31; for the repaint see M00635)

- 1970 ERII (Howard – Alamy AK2N0X)

- 1970s King Billy, Park Street, Coleraine (see above)

- 1971 British Pathé film of “Belfast Slogans”

- fl. 1971-07 (but possibly pre-dating the Troubles) King Billy, location unknown. The shields on either side read “Ulster” but are strikingly similar to the emblem of the UDA. (This mural is perhaps the one in Ken Howard’s 1978 painting for the IWM “King Billy And The Brits”.) (X09232)

- 1971 King Billy 1690, Westmoreland St (Le Garsmeur – Alamy EEC6BT and EEC4EG)

- 1971 Union Flag (Le Garsmeur – Alamy EEAMP4 and EEC4EG)

- 1971 “Welcome To All Brethren”, Edenderry St, Belfast, (Le Garsmeur – Alamy EEAM68)

- 1971 “Welcome To All Brethren” with star, Edenderry St, Belfast (Le Garsmeur – Alamy EEC6R6)

- 1972 “By this we live” with Union Flag, Shankill Rd, Belfast (Alex Bowie – Getty)

- 1972 “Keep Ulster Protestant” Memel Street, Belfast (Le Garsmeur – Alamy EEC2Y1)

- 1972 “Ulster REM 1690” (Le Garsmeur – Alamy EEC31C)

- 1972 “For God and Ulster” (Le Garsmeur – Alamy EEC5PX)

- 1972 “We shall not forsake the blue skies of Ulster for the grey mists of an Irish republic” Shankill Rd (Alex Bowie – Getty)

- 1972 “Red Hand UVF UFF” Shankill Rd, Belfast (Alex Bowie – Getty)

- 1972 “UVF No Surrender 1690” with Union Flag, Taylor St (Alex Bowie – Getty)

- 1972 “One faith, one crown, no pope in our town” Shankill Rd, Belfast (Alex Bowie – Getty)

- 1972 “Ulster shall be free (UDA)” (Alex Bowie – Getty“, “(UDA) Ulster will fight” (Alex Bowie – Getty) and “Ulster is Protestant” (Alex Bowie – Getty), Shankill Rd, Belfast

- 1972 “Fuck the IRA” Shankill Rd, Belfast (Alex Bowie – Getty)

- 1972 King Billy “No surrender”, Shankill Rd, Belfast (Alex Bowie – Getty)

- 1972 King Billy with “Remember 1690”, “King William III Of Orange 1690” and “One faith, one crown, no pope in our town”, Midland St, Belfast (Rolls Press – Getty | X05802)

- 1975 “REM 1690/Ulster not for sale/Paisley Forever” (Homer Sykes – Alamy A7N93B)

- 1975 King Billy on a white horse without any background (Conrad Atkinson – Tate)

- 1975 “Ulster” with a Union flag (Conrad Atkinson – Tate)

- 1975 “Up UVF” with Union flag (Conrad Atkinson – Tate)

- 1970s? King Billy in Union St, Portadown (Loftus 1982 p. 62 | X05384; M00806)

- 1976 “Bill Kernaghan bluffed the court” Shore Rd, Belfast

- 1976 “Sectarianism kills workers” Belfast (Alex Bowie – Getty) This piece is also listed in the appendix to Visual History 02 since no location is given and the sentiment could come from either sect.

- 1977 ERII 25th (Le Garsmeur – Alamy EEC6N6)

- 1977 “Remember The Loyalist Prisoners” Howard Street South, Belfast. Originally with the dates of QEII’s 25th anniversary (see C00629) but these dates were later removed (see R1009).

- 1978 A standing “William III” with “Ulster Forever” (Conrad Atkinson – Tate)

- 1979 “No pope here – Ulster forever” Rockview St, Belfast (Alan McCullough)

- 1970s Red Hand Commando in sunglasses, the Fountain, Londonderry (Rolston 1991 p.33)

- 1970s UVF murals in the compounds of Long Kesh (see discussion above)

- Loyalist Paramilitary Murals c. 1981 – mentioned/presented in Rolston 1991

1981 Waterside, Londonderry masked loyalist (p. 41)

1982 Lecale St, Belfast “VAS” red hand (p. 32)

1983 Inverna St, Belfast “RSD” red hand (p. 36)

1983 Donemana toilets UVF (p. 38 or plate 10 in Rolston 1992)

und Fountain, Londonderry RHC vol in sunglasses and UDA emblem (p. 33)

und Woodvale, Belfast volunteer bust (p. 41)

und Woodvale, Belfast UDA/UVF/YCV (p. 41) - 1982 Ulster Banner in shield form surrounded by Union flags in Bond’s Place, Londonderry (see above)

- 1982 “1688-1690 Ulster” Bond’s Place, Londonderry (see above)

- 1982 Commonwealth flags, Bond’s Place, Londonderry (see above)

- 1982 St Andrew’s Saltire, Union flag and Ulster Banner, Bond’s Place, Londonderry (see above)

On to Visual History 02 – The Catholic Insurgency

Written material copyright © 2017-2026 Extramural Activity. Images are copyright of their respective photographers.

Back to the index of Visual History pages.