Introduction – The Dying Cú Chulaınn

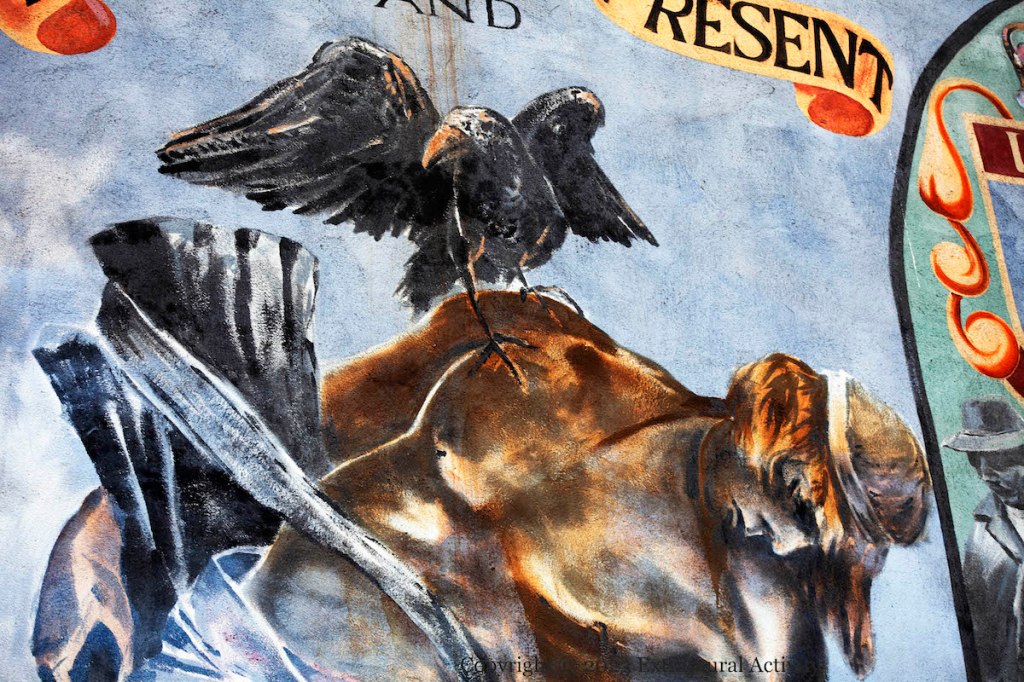

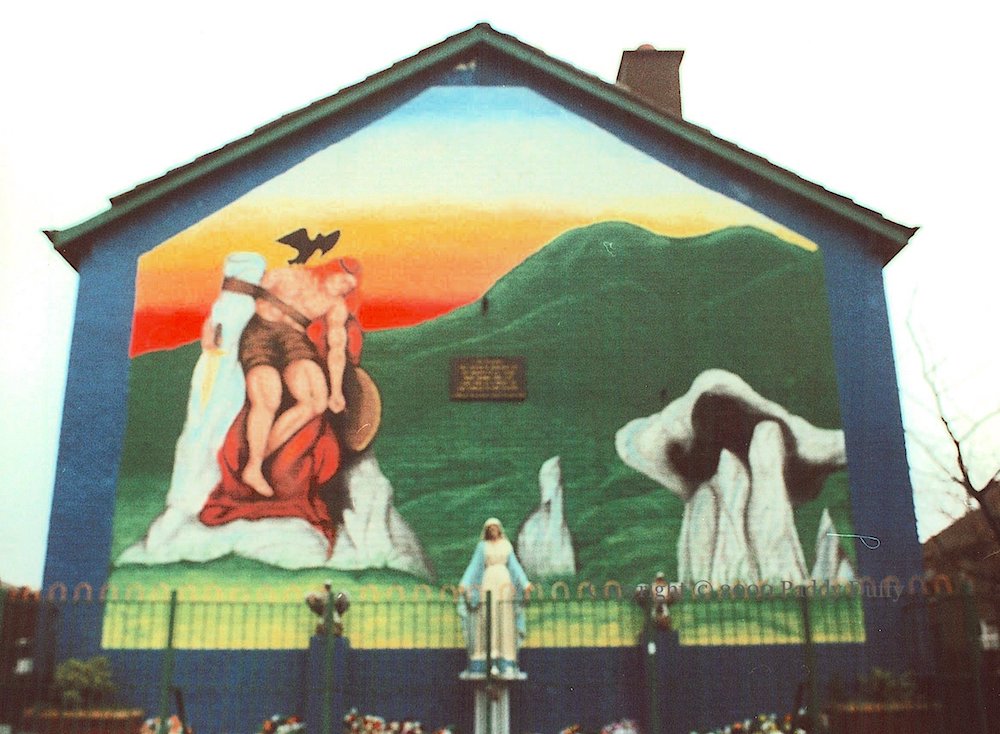

The ancient hero Cú Chulaınn – and more specifically, Oliver Sheppard’s depiction of the death of Cú Chulaınn – has appeared in both republican and loyalist murals.

Cú Chulaınn’s death is described in the Book Of Leinster. His renown as a warrior has made him a target. At the behest of Queen Medb of Connacht, Lugaıd sets out to find and kill him, and hits him with a spear. Mortally wounded, Cú Chulaınn ties himself to a standing stone so that he will die on his feet. Only when a raven lands on his shoulder do his attackers know that he has died.

This event is only the last in a long-running battle between Ulster and Connacht; Cú Chulaınn is most famous for single-handedly holding off the forces of Queen Medb by months of single-person combat. He holds his ground for long enough that the other heroes of Ulster can recover from the curse that made them sick and can now take up the fight.

The exploits of the warrior Cú Chulaınn might serve as suitable subjects for murals. He is also famous, as the young Setanta, for the story by which he gains his later name, by killing and taking the place of the hound (cú) of Culann. But Cú Chulaınn is never depicted in murals as a warrior and those which show him hurling promote Gaelic games and not militant republicanism. By far the most frequent portrayal of Cú Chulaınn has been the Cú Chulaınn from the story of his death, and of the death scene as made vivid by Oliver Sheppard in a bronze statue modelled in 1911.

The reason the statue appears in CNR murals is Cú Chulaınn’s association with the 1916 Easter Rising and armed Irish resistance thereafter. The tie to the Easter Rising was made in 1935 when, at the request of Irish prime minister Éamon De Valera, the statue was installed in the Dublin GPO (General Post Office) on the anniversary of the Rising. The GPO was a rebel stronghold during the 1916 Rising and had been destroyed by the fighting and shelling. It had been re-built in 1929 by what was by then the Free State government. (There is a separate Visual History page on the archetypal depiction of the Rising in the GPO – Walter Paget’s painting The Birth Of The Irish Republic.)

According to one scholar, the statue’s use to symbolise the Rising “reflect[s] the ideology of the Celtic Revival and the Irish political resurgence, as expressed by the narratives of Standish O’Grady and Patrick Pearse’s ideology of ‘blood sacrifice’; the image of the pietà with the body of the dead Christ underlies Sheppard’s sculpture” (Turpin 1997, p. 73). Another similarly writes, “By the time Oliver Sheppard’s pieta-like bronze of Cúchulainn was erected in the GPO in 1935, the identification of Pearse, Cúchulaınn and sacrificial martyrdom within the public imagination was complete” (Sisson n.d., p. 12; also available in spoken form).

In each of these comments on Sheppard’s statue we find two points: that Cú Chulaınn’s death was used to represent the Irish nationalism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and, that Sheppard presents Cú Chulaınn’s death in a Christ-like fashion.

The first point puts the statue’s placement in the GPO in the wider context of the “Celtic Revival”, to include both the Gaelic Revival and Irish Literary Revival. Cú Chulaınn’s exploits and death were made widely known in a 1902 translation by Lady Gregory, whose interest in Irish folklore had been stimulated in part by the many literary renditions of the legends written by Standish James O’Grady, her cousin and “father of the Celtic Revival”. Sisson claims that “Much of Cúchulainn’s dominance as a nationalist icon within contemporary culture comes from his association with Patrick Pearse … In 1898, at only 19, [Pearse] published a series of three lectures on Cúchulainn and the Red Branch Cycle in which he extolled the figure of Cúchulainn as a role model for masculinity and the Gaelic ideal … combin[ing] the artistic sensibility of the Celtic … with the pagan physicality of the Gaelic” (pp. 6-7)

The Revivals of the Irish language and of Celtic folklore and culture generally went hand-in-hand with the fight for Irish independence (O’Grady, however, was a unionist). The fight would require sacrifice, a prospect that Pearse seemed to relish, or at least, think salutary. In 1913, in a speech entitled The Coming Revolution, Pearse concluded, “I am glad, then, that the North has begun. I am glad that the Orangemen have armed, for it is a goodly thing to see arms in Irish hands. I should like to see the A. O. H. armed. I should like to see the Transport Workers armed. I should like to see any and every body of Irish citizens armed. We must accustom ourselves to the thought of arms, to the sight of arms, to the use of arms. We may make mistakes in the beginning and shoot the wrong people; but bloodshed is a cleansing and a sanctifying thing, and the nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood. There are many things more horrible than bloodshed; and slavery is one of them.” (italics added)

Donal Fallon, writing in the Indo, puts Pearse’s call for blood sacrifice in the context of similar rhetoric surrounding the Great War, including by John Redmond, who thought that common sacrifice on the battlefields of Europe would unite Irishmen of both sects. There was a lot of it going around, it seems: for “blood sacrifice” in Connolly and the ICA, see Ferguson. Reeder traces the idea of “noble death” from the Rising to the hunger strikes and from the Somme to the UVF.

An article by Jenkins considers “how easily and naturally Christian rhetoric can be adapted to the cause of warfare and violence”. The absence of any political agenda in the Christ’s sacrifice meant that it could then be extended to any mundane ideology that currently required its adherents to risk their lives. Jenkins discusses both sides in the Great War and Pearse’s language of sacrifice in Ireland. Pearse himself had related the struggle for Irish independence to the divine sacrifice when he spoke of the “Christ-like sacrifice” of Robert Emmet (History Ireland).

The two scholars initially quoted detect in Sheppard’s statue aspects of Michelangelo’s pietà (“pity”) in which Mary holds the body of her dead son after he has been taken down from the cross. Sheppard’s statue is perhaps from a moment just before the pietà – Cú Chulaınn is still tied to the rock that holds him upright but is nonetheless akin to the Christ in that he is slumped over and at the point of death, and in that he is not wearing any armour but instead is nearly naked, wearing only a head-band and loin-cloth. (Compare Sheppard’s statue with Leyendecker’s painting of Cú Chulaınn in battle, also from 1911.) These features might seem to the fore in statue, relative to Cú Chulaınn’s career as a warrior, as his sword and shield are lowered by his sides. At the end, when death is near and the arms fall away, there remains only the impetus for war, self-defense and the desire for self-government, or even just sacrifice itself, and this sacrifice can be transferred to whatever particular political struggle is on-going, whether in the streets of Dublin or the trenches of Europe.

Hence we can see in Sheppard’s statue the pre-Christian Cú Chulaınn related to the sacrifice of the Christ, and these in turn are related to the Irish nationalism of the time, first culturally, as part of the Celtic Revival, and second militarily, by being placed in the GPO.

Without denying the Christ-like aspects of Sheppard’s statue, it’s clear from the visual record – some of which is presented below – that in murals of the modern era (1969 to the present) only the armed struggle is represented by Cú Chulaınn while the passive sacrifice of the hunger strikes is represented by appealing directly to the Christ. Whatever his Christ-like attributes, Cú Chulaınn is too strongly associated with fighting and the hunger strikes too-strongly associated with non-violent sacrifice for Cú Chulaınn to be used to represent the hunger strikes.

The other main point of discussion below is the use made by loyalist paramilitaries of Cú Chulaınn.

The Spread Of The Dying Cú Chulaınn

An Irish Times retrospective called De Valera’s use of Sheppard’s statue “an inspired act of appropriation” because it was created prior to 1916 and concerned an inter-Irish dispute – Ulster versus Connacht. But since the statue was part of the Celtic Revival, which stood for the independence of Irish culture, it was easily applied to the Rising, which stood for the political independence of Ireland.

The appropriation was effective. WB Yeats’s poem The Statues, published in 1938, put Pearse and Cú Chulaınn together in the GPO, fighting to restore Ireland to the glory of Greek proportion and escape the “filthy modern tide”:

“When Pearse summoned Cuchulain to his side.

What stalked through the Post Office? What intellect,

What calculation, number, measurement, replied?

We Irish, born into that ancient sect

But thrown upon this filthy modern tide

And by its formless spawning fury wrecked,

Climb to our proper dark, that we may trace

The lineaments of a plummet-measured face.”

More officially, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Rising, Sheppard’s Cú Chulaınn made an appearance, along with Pearse, on the nation’s ten shilling coin (with “Éırí Amach Na Cásca 1916” on the edge (WP) (Image at IrishCoinage). (For the 75 anniversary, Cú Chulaınn appeared on a stamp.)

While the Irish state’s use of Cú Chulaınn was tied to the Rising, in the north Sheppard’s connection of Cú Chulaınn to the 1916 Rising was extended to those who were still fighting for Irish independence. As a result, the legend of Cú Chulaınn and the Sheppard statue are familiar in CNR muraling in the modern era (1981 to the present), representing both the Easter Rising and the IRA of the Troubles.

The first mural to show Cú Chulaınn is from St James’s in west Belfast. A clothed Cú Chulaınn is tied to a large letter “ı” at the start of “I ndíl [ndıl] ċuıṁne”: “in fond memory” of the eight local people listed on the plaque as having the “spirit of freedom”.

In the Turf Lodge mural by Mo Chara Kelly (shown below), Sheppard’s Cú Chulaınn is surrounded by portraits of the seven signatories of the Proclamation and Pearse’s Mıse Éıre (which is discussed below).

In the New Lodge, a 1916 rebel and Cú Chulaınn are placed on either side of a large Celtic Cross which sports a lily and gal gréıne (sunburst – symbol of Na Fıanna) and a line from the Proclamation.

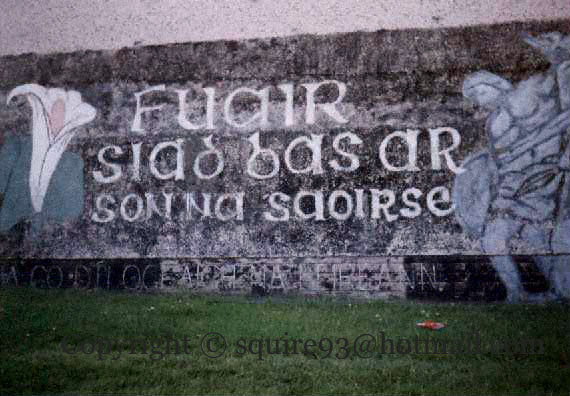

In Lurgan, Cú Chulaınn appeared next to an Easter lily, making this a reference to 1916 volunteers who died “ar son na saoırse”, despite the neat graffiti along the bottom reading “Bua go dtí Óglaıgh Na hÉıreann” [Victory to the IRA].

Without any reference to 1916, the mural just below lists dead IRA volunteers from the Derry Brigade alongside Sheppard’s dying Cú Chulaınn.

The example above is only one of the many murals (not to mention memorial plaques and stones) placing the dying Cú Chulaınn alongside deceased volunteers:

Belfast

– Ballymurphy IRA Roll Of Honour (M01641)

– Ballymurphy IRA trio (X00348)

– Lenadoon IRA (X05917)

– Lenadoon IRA (Roddy’s) (M05544)

– lower Falls OIRA (X08203)

– Ard An Lao ICA and “old” IRA (X08359) – this dying Cú Chulaınn appears in armour rather than a loin-cloth

Derry

– Bogside IRA (X10903)

– Brandywell IRA (X10943)

– Creggan IRA (X04340)

Strabane

– West Tyrone IRA (M04563)

Armagh

– Athletic Grounds (T03369)

Sheppard’s Cú Chulaınn is almost always recreated faithfully in CNR murals. One exception is the painting (by Marty Lyons and a Short Strand artist) in a pair of large paintings in the Ulster Museum. In various respects, this indoor painting is made to resemble the classic outdoor mural – the board has been given an apex to resemble the gable wall of a house and a border of Celtic knot-work serves as a frame. In a break with tradition, however, Francis Hughes of the IRA takes the place of Cú Chulaınn, a tourniquet on his right leg, an assault rifle dangling from his wrist, and instead of the raven that signified Cú Chulaınn’s death there is the symbol of republican political prisoner, the lark, which appears in the apex of many other republican murals. (Also unlike murals, the artists have signed and dated the painting, in the lower right corner: “Danny D, M Lyons, 2000”.)

Despite its originality, it is easy to read the Hughes Cú Chulaınn, given the prior associations of Cú Chulaınn with the Easter Rising, the IRA, and the fight for Irish independence generally. And in case there were any doubt or difficulty in interpretation, to Hughes’s left are two old women, one of whom is carrying Pearse’s poem Mıse Éıre in which Ireland in the form of a woman laments that she gave birth to Cú Chulaınn but has now been abandoned (to the British) by her children. Francis Hughes is thus one of those rare people in the mould of Cú Chulaınn who is willing to defend Ireland and if necessary with his life.

Hughes did not die at the time of this “last stand” against soldiers of the Parachute Regiment near Lisnamuck – he was captured alive (see image below) – but he would die three years later in the 1981 hunger strike while serving 83 years for killing one soldier and wounding another in the shootout, and for six years’ worth of prior offences (WP). But his eventual death is confirmed in the painting by the beret and gloves at his feet; these are typically seen on the coffins of IRA volunteers. (Here is a mural placing them in the apex of an Easter Rising mural.)

Limits On The Connotation Of Cú Chulaınn (Dying Or Otherwise)

It seems that for republicans, the dying Cú Chulaınn serves as a symbol of military sacrifice only. It is not used to represent the activity of living volunteers, though for loyalists, as we will see below, it is used for military activity only. On the other hand, while Sheppard’s Cú Chulaınn might have similarities to the pietà, as the Turpin and Sisson quotes given at the top of this page suggest, Sheppard’s Cú Chulaınn is not employed as a symbol of the hunger strikers, even though the hunger-strike is presented as Christ-like in various murals.

There is one case that appears to use Cú Chulaınn for (IRA) active service, in Lenadoon (C01019). Cú Chulaınn is tied to a trunk but also sitting on a log; there is a ?phoenix? on his shoulder and he holds a knife. The year given for this board is 1996, which is after the cease-fire. So, this piece is something of a mystery. (Compare the hooded IRA gunmen in the Markets in 1997.)

In Ligoniel, Cú Chulaınn was used somewhat unusually to stand for the sacrifice of local people (who were not volunteers). The plaque in the centre asks Muıre, Banríon Na nGael, to pray for all those from the area who lost their lives and it was previously at the centre of a large (painted) Celtic Cross (T00312). This was repainted with the Cú Chulaınn mural and the Mary statue added in front (image below). (Both were later replaced by a (stone) Celtic Cross, a stone to the IRA’s Declan McCluskey, and an additional plaque immediately below the first which named the dead, only one of whom was a volunteer (M04797).)

Mo Chara (and others) painted the 1991 Cú Chulaınn Cróga in Armagh, below, which does not make any reference to either dead volunteers or dead locals from either end of the 20th century. Nor again did it refer to active volunteers. The title (behind the bin) and the title in the apex are from Pearse’s Mıse Éıre but the mural lacks any pictorial reference to subsequent resistance. Mo Chara’s 2005 Glenbawn Cú Chulaınn (X02580) is also purely cultural, as is the 1990 montage (perhaps depicting the Táın Bó Cúaılnge) in north Belfast (M00898).

(There was a Cú Chulaınn Cróga in Lurgan (D00510). This showed Fitzpatrick’s Nuada in armour but was re-titled as “Cú Chulaınn”. The date for this piece is unknown.)

Finally, here is the only case that we know of that shows Cú Chulaınn alongside the hunger strikers: a 1998 painting in Derry which begins a series of portraits of the 1981 dead with a crude Cú Chulaınn. When the piece was repainted in 2001, Cú Chulaınn was not included.

The sacrifice of the hunger strikers is represented directly by the Christ (and Mary). One mural showed hunger strikers on the cross (see T00048). Another invokes the pietà directly: a dead hunger striker lies in the arms of his parents having been removed from the suffering-place that is “Long Kesh 1981”

The same artist who painted Long Kesh 1981 – Con – also painted a mural showing a hunger striker being visited by Mary under the New Testament (Matthew 5:6) phrase “blessed are those who hunger [and thirst] for justice” (M00131), and another surrounding Dali’s Christ Of St John Of The Cross with portraits of the men on strike at that time (shown in the Visual History page on the 1981 murals). His aim was to reach those west-Belfast nationalists whose Catholicism would not permit sympathy for paramilitary activity but who might recognise the passive sacrifice of the hunger strike (source: in-person conversation).

Using Cú Chulaınn would not have sufficed to make this argument, even with the Christ-like aspects of Sheppard’s statue, as Cú Chulaınn is also a warrior and, by the time of the hunger strikes, firmly associated with the 1916 Rising. In other words, the Cú Chulaınn imagery used to represent the republicans who died from bullets and bombs needed to be cleanly separated from the religious imagery used to represent the republicans who would die on hunger strike.

In the years since 1981, the direct appeals to the Christ have disappeared and memorials to the dead hunger strikers have used Celtic crosses and religious invocations (in Irish) for the safety of their souls.

So, it seems that both terms in “dying Cú Chulaınn” map strictly onto the corresponding term in “deceased volunteers”, where “deceased” excludes active gunmen and “volunteers” excludes hunger striking (and perforce the blanket and dirty protests) as a mode of protest.

The Living Cú Chulaınn

If the dying Cú Chulaınn is used as a symbol of dead CNR volunteers, we might expect the few representations of the living Cú Chulaınn to be used for active resistance. There are a few appearances of Cú Chulaınn as a living warrior, but none of them is associated with militant nationalism. (PUL uses of Cú Chulaınn – always living – will be included in the next section.)

One showed a young Cú Chulaınn sitting under a tree, with spear and shield off to the side, next to a harp, with a dove flying between him and the strolling Queen Maeve, suggesting … peace between Ulster and Connacht? between north and South? (X00434 | J1907) The piece is one of two in the street produced as part of the “Positive Art – Millennium Awards” project, i.e. it had funding from the (UK) Lottery Fund and would have been restricted in what it could portray.

Also in Ardoyne, Cú Chulaınn was painted as a warrior for the Ard Eoın Fleadh Cheoıl, a cultural event.

Another is in the small (CNR) Dunclug area of Ballymena, aimed at children and playing up the divine and mythical elements of Cú Chulaınn’s biography (T02516).

Finally, there is a piece of stained glass in Belfast City Hall concerning the Táin Bó Cúaılnge – a purely cultural representation.

When other Celtic warriors, or generic Celtic warriors, are painted, the mural in question is not in support of militant republicanism but rather of a distinctly Irish identity. The Visual History page about The Influence Of Jim Fitzpatrick includes many murals depicting Nuada and other ancient warriors, but these are never directly tied to militant republicanism.

A few possible exceptions: one, by juxtaposition of a Celtic warrior next to a funeral volley (M00263); Pearse’s Mıse Éıre is also included. Another might be a Derry Brigade roll of honour in which an ancient warrior and modern paramilitary stand together, the paramilitary in funeral gear and the mythological figure is armed and active (see M01157, which was later repainted in colour M00319). In this mural, the hooded modern figure symbolises the death of the volunteers listed in the roll of honour, perhaps leaving the ancient warrior free to represent their militant activity.

Another exception might be the use of an ancient shield as a synedoche for Celtic warriors, as part of a history of armed resistance. Out Of The Ashes Of 1969 (X00857) requires the use of arms only (rather than figures) because of the extent of history covered: it combines an assault rifle symbolising the Troubles-era IRA (specifically the Belfast Brigade), a Thompson gun symbolising the Civil War IRA, the emblems of Cumann Na mBan and Na Fıanna from the Easter Rising, pikes symbolising the 1798 and 1803 rebellions, and a Celtic shield and sword symbolising the ancient … struggle against British occupation?

Another version of the living Cú Chulaınn is as Setanta, the pre-heroic Cú Chulaınn, who is used as a symbol of Gaelic games. In two west Belfast murals this Setanta/Cú Chulaınn is a young child (Ross Road X01667 | Gaelscoıl An Lonnáın X12566) while Jim Fitzpatrick’s image of Cú Chulaınn hurling as a young adult has been used in several murals (for these, see the Visual History page on the influence of Jim Fitzpatrick). One mural in Derry showed a warrior Cú Chulaınn (actually Fitzpatrick’s Nuada) but replaced his sword with a camán (X03632).

In general, then, the living Cú Chulaınn/Setanta (or any kind of Celtic warrior) is absent from murals about militant activity and stands instead as a symbol of Irish history and culture.

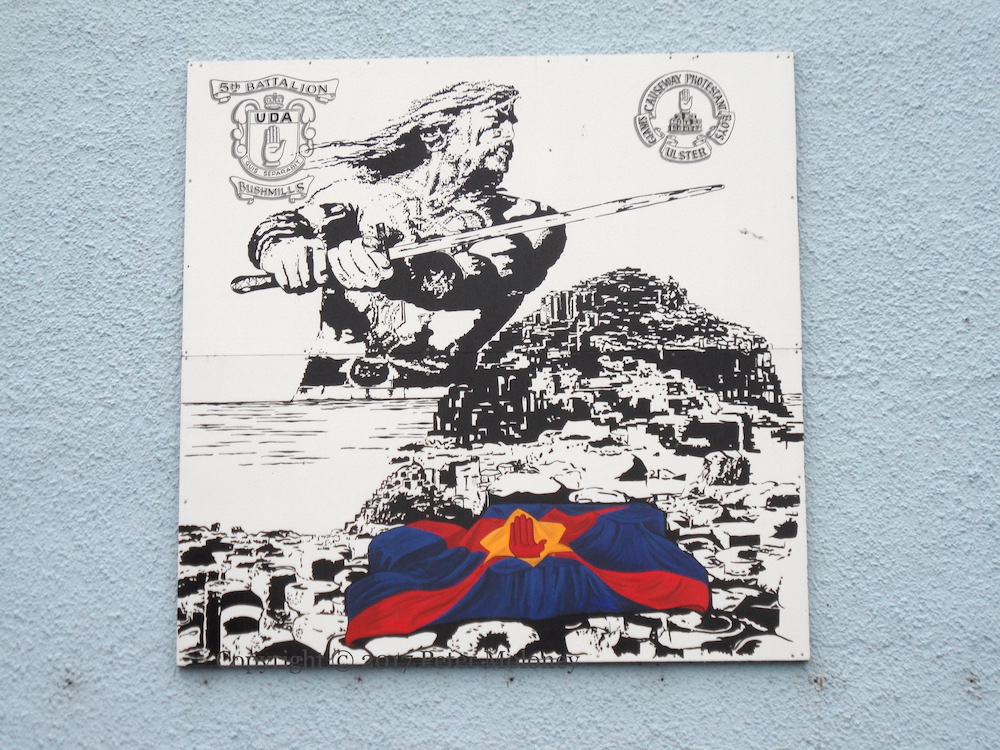

Cú Chulaınn In PUL Murals

Girel-Pietka’s statement on the appearance of Cú Chulaınn in the GPO says that “Irish Republicanism … appropriated the famous “Champion of Ulster,” paradoxically emphasizing the fact that national culture cannot be confined within the 1922 borders” (Girel-Pietka 2016, p. 82). In other words, Cú Chulaınn as hero of Ireland (rather than Ulster) meant the 32 counties, rather than the 26 that now formed the political unit of Ireland. A reverse form of this point, re-asserting the original incongruity of representing a unified Ireland using a character from a disagreement between Ulster and Connacht, allowed loyalists to appropriate Cú Chulaınn for themselves.

In the second of the pieces in the Ulster Museum – the PUL piece, painted by Dee Craig (Fb) – the raven sits on the shoulder of a Cú Chulaınn who has a red cloak and carries a Northern Ireland (Ulster Banner) shield. “Down through the years, his shadow has cast a new breed of Ulster defender”: a (loyalist) hooded gunman. Thus, while Cú Chulaınn is the “Ancient defender of Ulster!”, loyalist paramilitaries are its modern defenders. (The B Specials (and UDR) can also be slotted in as “Ulster’s past defenders” – the UDR is concurrent with the UDA but ceased to exist in 1990.)

The dripping red hand in the top left is the ‘red hand of Ulster’; one version of the origin-story for the red hand is that the man who avenged Cú Chulaınn’s death made a bloody hand-print to indicate his completion of the deed. Most people, however, will think of the legend that in a race to be first to touch the land of Ulster one contestant (perhaps Érımón Uí Néıll) cut off his hand and threw it ahead of the others. (This legend was depicted in a lower Shankill mural and narrated in an east Belfast mural: The Strangest Victory In All History.)

The use of Cú Chulaınn in PUL muraling goes back (at least – there was a PUL Cú Chulaınn in Long Kesh) to a 1992 UDA mural in east Belfast (shown below), in which Sheppard’s statue of the dying Cú Chulaınn is cartoonishly reproduced, especially when it comes to the “raven” on top. The shield bears the flag of Northern Ireland (the Ulster Banner) and is moved to the front alongside an armed – but unmasked – volunteer who is described as one of “Ulster’s present day defenders”.

Both defenders, ancient and present-day, stand on a Union Flag. Cú Chulaınn might plausibly be the “hero of Ulster” against invasion from Connacht, but can he be a defender of the United Kingdom, too?

The link between Ulster/Northern Ireland and the Union is made in the hypothesis that Cú Chulaınn was a member of the Pretani (or in old Irish, the Cruthın) and that the Cruthın were a pre-Celtic British race that had settled in Ulster and engaged in wars with the Irish Gaels before fleeing in the 600s, only for their ancestors to return a thousand years later during the plantation of Ulster. Thus, the claim “Northern Ireland is British” goes back not just to the plantation or William Of Orange but to ancient Ireland, and has the same standing as the claim “Northern Ireland is Irish”.

This hypothesis was first suggested by Thomas O’Rahilly in Early Irish History and Mythology (1946) and further developed by Ian Adamson in The Cruthin: A History of the Ulster Land and People (1974 – the cover of the book can be seen on the Visual History page on Jim Fitzpatrick).

Adamson’s hypothesis was taken up by the UDA, who lacked the UVF’s origin-story of the 1912 Ulster Volunteers. Cú Chulaınn as the “ancient defender of Ulster” allows the UDA to think of themselves as “modern defenders” of Northern Ireland’s place within the Union.

In most UDA murals that feature Cú Chulaınn, however, the connection to the United Kingdom is taken as read and not portrayed (with a Union Flag or other device), though doing so might have been a good idea in order to supplant the obvious connection between Cú Chulaınn and Ireland.

For example, here is an early (c. 1996) mural in the Lincoln Court area of Londonderry, which presents a living Cú Chulaınn as an analogue to loyalist paramilitaries and prisoners of war (“LPOW” on the right):

Cú Chulaınn was also briefly adopted by the UVF. He is called “champion of Ulster” in this Rathcoole mural, and the Red Hand Commandos (a UVF group) are described as the descendants of the Red Branch Knights, the troop to which Cú Chulaınn belonged: “Red Branch Knights in the beginning, Red Hand Commando until the end – defenders of Ulster”.

There has been one other PUL mural mentioning the Red Branch Knights, in (UVF) east Belfast. Presumably, that is Cú Chulaınn on the left, though here in active pose with sword and spear, as he represents the Red Branch as “ancient warriors of Ulster”, while the hooded RHC gunman on the right represents the “present-day defenders of Ulster”.

These are (to our knowledge) the only recorded uses of Cú Chulaınn by the UVF around the time of his adoption by the UDA (see below for a much later possible UVF use).

It is worth noting that, contrary to what was asserted above about the dying Cú Chulaınn never representing active republicans, in PUL muraling – whether UDA or UVF – Cú Chulaınn is always tied to active paramilitaries. There is no mural using Cú Chulaınn as a symbol of dead loyalists, perhaps because their history as “defenders” of Northern Ireland only begins with the Troubles. (We will see below Cú Chulaınn in the context of the 36th Division.) The purpose of Cú Chulaınn in PUL murals is to modern-day (Troubles and post-ceasefire) physical-force loyalism as an on-going extension of a long-standing tradition of violence.

(Note also that in the images above from Freedom Corner and Rathcoole the name “Cú Chulaınn” is rendered as “Cúchulaınn” – all one word and with a fada (long mark) over the “u”. In the second version of the “Freedom Corner” mural in east Belfast (just below), the name is given as “Cuchulainn” (without a fada) and this is how it has typically been rendered in PUL contexts from this point on.)

(This version (and the third) replaces the Ulster Banner on the shield with the proposed flag of an independent Northern Ireland. Despite the idea that Cú Chulaınn was a Cruthın who defended his tribe from southern attack, UDA thinking acknowledged that Northern Ireland was also home to many people with a different heritage, and so proposed an independent Northern Ireland.)

Cú Chulaınn also appeared in the (UDA) lower Shankill and in (UDA) Highfield. The Cú Chulaınn in the Shankill is not at all Sheppard’s Dying Cú Chulaınn but the most active representation of all, yelling and reaching for the sky with his sword as he prepares to take on the Connacht horde.

The Highfield rendition shows a sacrificial version of the Dying Cú Chulaınn, without shield or sword (and tied not to a rock but to an upright log or broken-off tree-trunk (or cross??)). Despite the lack of weapons, the context is still present-day paramilitarism: this is a UDA mural – with two images to the right of volunteers with sunglasses (above) and balaclavas (below), though no weapons are depicted.

The wrinkle here is that memorials to the 36th Division of WWI are included in the lower left – an indication that Cú Chulaınn’s moniker as “(ancient) defender of Ulster” can equally be transferred to the UVF, though here by the circuitous route of the Ulster Volunteers who joined Kitchener’s army and fought in Europe.

(In the upper left is the emblem of the UDU, the Ulster Defence Union (X00283), an additional origin-story found in 2007 which gave the UDA a history going back to the turn of the twentieth century.)

The Highfield mural was later joined by a series of marble panels. The date (c. 2015) and extent (five panels) demonstrate the commitment of the UDA to Cú Chulaınn. As in the mural, Cú Chulaınn is presented alongside the 36th Division, with bookending panels, two on each side, showing (on the left) Messines tower and a few lines from a Ronald Lewis Carton poem Réveillé (though given a more ‘victorious’ ending) and (on the right) a few lines from Duncan Campbell Scott’s To A Canadian Lad Killed In The War and Thiepval tower.

The five biographical panels in the middle focus on Cú Chulaınn’s age – the seventh panel emphasises that Cú Chulaınn was only 17 when he held off Maeve’s forces – which is perhaps a similarity with those who joined the 36th Division, but as with the Messines and Thiepval memorials included in the mural, how the “defender of Ulster” is connected to the defense of Europe is obscure, unless it is by the generic theme of blood-sacrifice discussed previously.

The map included in that same panel divides Ulster into four territories: the Cenél Conaıll in the north-west, the Cruıthní in the north-east, the Uí Nıall [Uí Néıll] in the south-east, and Cú Chulaınn in the south-west.

Adamson’s hypothesis has not been widely adopted – there is no evidence of a separate race in either a DNA survey or an archaeological survey (p. 177) and so it cannot be judged where the Cruthın might have originated – but it does seem to have been (again) taken up by the UVF, or at least, by the Ulster Scots association now promoting the hypothesis, dalaradia.co.uk (cf. pretani.co.uk), that is permitted to post in UVF areas. A number of boards similar in design and colour-scheme to the one below have appeared – see also the nearby Kingdom Of Dalaradia and in UVF/RHC Rathcoole Kingdom Of The Pretani and On The Occasion Of Her Platinum Jubilee. This one – which is outside Crusaders’ soccer ground in a UVF area of north Belfast – is the only one to feature Cú Chulaınn (and a warrior from Game Of Thrones), along with a battle between the tribes of Antrim and Down in a period much later than Cú Chulaınn; the battle is illustrated by a Jim Fitzpatrick picture, but, ironically, this is Fitzpatrick’s take on the Battle Of Moira, after which (according to the Adamson hypothesis) the Cruthın retreated to Britain.

Although the Cruthın-as-Britons hypothesis has been found wanting by scholars, it too is a remarkable piece of appropriation, in that it brought out one of the incongruities of the original appropriation of the Cú Chulaınn myth to represent the fight for Irish freedom, namely that an inter-Irish conflict (between Ulster and Connacht) was supposed to represent the conflict between Ireland and Britain. Cú Chulaınn’s defence of Ulster more naturally matches the loyalist fight to prevent the absorption of Northern Ireland into the Republic, though it is not clear that the hypothesis has spread widely among enough among the PUL community to prevent most loyalists from intuitively identifying Cú Chulaınn as Irish.

(A footnote: Finn McCool was also given the descriptor “defender of Ulster” in a Bushmills board. A second, later, board placed Finn next to the UDA’s proposed flag for an independent Northern Ireland.)

Conclusion

In both sects, there is a desire to provide ancient roots and a continuous lineage that reaches the present day.

On the CNR side, Cú Chulaınn is tied to the 1916 Easter Rising and the Troubles-era IRA but not to the hunger strikers, despite the extent to which Sheppard’s statue of the death of Cú Chulaınn reminds one of the pietà.

On the PUL side, Cú Chulaınn is tied to modern (i.e. Troubles and post-ceasefire) paramilitaries (and, by association, but not explicitly, to the B-Specials and UDR) as “past defenders of Ulster/Northern Ireland”; Cú Chulaınn has primarily been used by the UDA but to a certain degree by the UVF; Cú Chulaınn is primarily a symbol of a loyalist militancy and secondarily of a distinct PUL heritage.

Post Script – Other Appearances

Cú Chulaınn is used in the anti-war mural in Lendrick Street. The “fallen from war” are those from east Belfast who died in WWI, the WWII blitz, and the Troubles; perhaps Sheppard’s Cú Chulaınn is added to give a sympathetic portrayal of paramilitaries – given the succession of “ancient defender” murals on the Newtownards Road, east Belfast loyalists will know to associate Cú Chulaınn with the UDA; whether they will also associate the statue with republican militants or with the dead from the Short Strand (the small Catholic enclave in east Belfast), is an open question.

Cú Chulaınn painted on a bare brick wall appears in the Salvador Dali mural in the Commercial Court entryway to the Duke Of York and Dark Horse bars. There is no such “bare” mural of Cú Chulaınn – this portrayal is meant to stand for all of the Cú Chulaınn murals, or perhaps all of the CNR ones. The mural combines various Belfast landmarks as floating fragments of memory in the disconcerting Dali style – perhaps brought on by the massive pint of Guinness from above which Dali shoots laser beams from his eyes. Jim Larkin also appears (T00769), on the other side of the central pint, perhaps specifically the statue in Donegall Street Place.

Key to reference numbers. Thanks to all of the following for the use of their images:

D = squire93@hotmail.com collection

M = Peter Moloney Collection – Murals

S = anonymous collection

T = Paddy Duffy Collection

X = Seosamh Mac Coılle Collection

Written material copyright © 2022-2025 Extramural Activity. Images are copyright of their respective photographers.

Back to the index of Visual History pages.