Introduction (Click here or scroll down for Images)

History

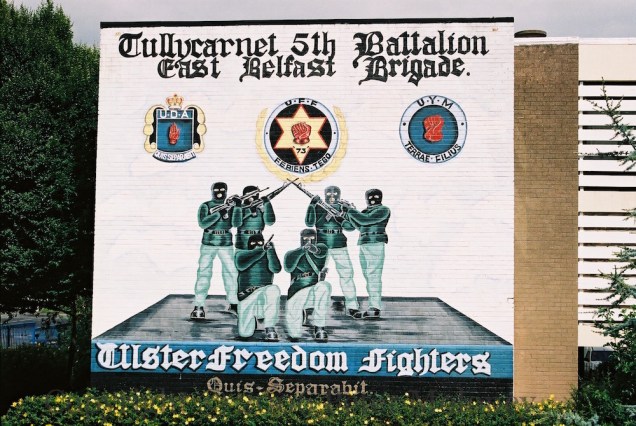

Even if the new, post-peace, Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive were non-functioning from 2002 onwards, it was clear that the peace would last. And as the peace wore on, the pressure grew on loyalist paramilitary groups to remove paramilitary murals and in particular those showing hooded gunmen.

Muraling

Visual History 08 described the introduction of two additional themes in PUL muraling – Ulster-Scots/Scots-Irish and the 36th Division — but it also mentioned various reasons why loyalist hooded gunmen did not go away in the years between 1994 and 2002: perception of the Agreement as a threat; uncertainty over the IRA’s resistance to decommissioning; use by paramilitary organisations to assert control over an area (including asserting control by one group over a fellow loyalist group); a lack of alternative themes. (Previous pages describe how hooded gunmen in active poses were no longer painted in republican murals after 1994 – Visual History 07 and Visual History 08 – and the direction that republican murals went in after the peace – Visual History 09).

These obstacles were overcome, beginning in 2003, by a handful of local initiatives, but a more substantial decrease in images of gunmen came as a result of intervention by state agencies. In 2004-2005’s “Art Of Regeneration” programme, the Arts Council NI and Belfast City Council allocated 2.4 million pounds to nine borough councils for a variety of projects, such as the installation of sculpture in public places, but also the removal or repainting of murals (Arts Council NI Press Release). The programme that the Shared Communities Consortium (led by the Arts Council and the Executive) launched in 2006 was explicitly called the “Re-Imaging Communities” programme, with an initial budget of 3.3 million pounds (Guardian); 500,000 pounds was added in October 2008 from the Department Of Culture, Arts, And Leisure.

The Guardian article just cited includes two quotes from Arts Council head Roısín McDonough expressing optimism about post-Agreement Northern Ireland the power of art: “[paramilitary murals] are about our troubled past. We are a society moving forward.” and “[re-imaging] is not just about replacing murals but also about getting people to think more broadly about how arts and artists can improve their quality of life in local neighbourhoods”. This page and Visual History 11 will illustrate the glacial speed of change.

Before the re-imaging period, most wall painting is sectional (that is, “sect-ional”, associated with either the CNR or PUL community) and oppositional (that is, it will be understood negatively by the other sect). State agencies want to support artworks that are not, or only weakly, sectional and oppositional, and to remove paramilitary and other strongly sectional and oppositional pieces.

In the effort to understand post-peace muraling and public paintings, it must be understood that constitutional politics saturates almost everything, to a greater or lesser extent, and that many sect identifiers are also oppositional – they will be understood to exclude or even offend the other side. While a few expressions of a sect’s identity might be perceived as harmless by the other side, there are very few themes to which both sects will say “Mine”. However, we want to leave conceptual space for imagery that is sectional (identifiably CNR or PUL) without being oppositional – see #4 Community murals in the taxonomy just below.)

Conceptual Interlude: A Taxonomy Of Themes

It is worth considering the extent to which different themes are sectional and oppositional. When we are thinking like the director of a re-imaging programme, we want to replace “hooded gunmen” images and symbols of physical-force organisations (as well as imagery concerning constitutional identity, such as flags) with a painting on a theme from as far down this list as possible. In (rough) order of decreasing impact:

1. Art that depicts historical events in the constitutional dispute – the [PUL] Williamite campaign in Ireland (1688, 1690), the [CNR] rebellions of the United Irishmen (1798, 1803), the [PUL] mobilisation against Home Rule (1893-1914), and the [CNR] Easter Rising (1916).

These are seen as an improvement over paramilitary murals, and as such the state agencies have funded works on these themes. Nonetheless, they are still sectional and oppositional, as every event that has been represented has been represented because it is significant enough to one of the sects.

2. Cultural murals — such as Celtic myths, Gaelic games, Gaelic music and dancing (all CNR), flute bands from both sects — can function as positive expressions of one sect’s culture, especially when viewed by people internal to the sect, but when viewed by outsiders, they often function oppositionally.

The Battle Of The Somme (1916) and the 36th Division (as distinct from the Ulster Volunteers of 1912) serves as an interesting case of cultural identity in the PUL community. The British Army and armed forces are strongly coded as PUL, but their deployment in the Great War is not related to the constitutional question and is not necessarily an expression of constitutional affiliation (because many Irish nationalists fought in the British Army).

We also include sports here. Team sports serve (all over the world) as a proxy for battle between communities. In Northern Ireland, soccer is the only team sport of note played by large numbers from both sects, and the teams that are best on each side have sectional as well as rivalrous roles. Thus, the pre-eminent Protestant team, south Belfast’s Linfield, is opposed to both Catholic-supported teams in general as well as to other Protestant teams, such as east Belfast’s Glentoran. There are different leagues in Northern Ireland and the Republic, and thus no chance that Catholic fans might back Linfield as the Belfast team in an all-Ireland cup final or in European competitions. Similarly, the two associations – the Irish Football Association and the Football Association Of Ireland (no, this is not a Monty Python joke) – are represented by two national teams: Northern Ireland and the Republic Of Ireland, respectively. Back at the club level, global media has allowed people to follow their favourite teams abroad. First to mind come the Glasgow teams Rangers and Celtic, which are supported along sectional lines, by Protestants and Catholics respectively. Teams from England and further afield might draw support from both Catholics and Protestants, but then … there are, with very few exceptions, no murals to these teams in both areas. There are very few shared cultural markers, and (to repeat), the rule seems to be: if it doesn’t identify us as distinct from them, it’s not worth putting on a wall.

Individual sports provide little relief. Heroes are mostly claimed by their local areas; boxer Carl Frampton is portrayed in both Tiger’s Bay (X01757) and the city centre (X02509), and golfer Rory McIlroy can be found in (non-sectional) south Belfast (X00559) and the city centre (again X02509).

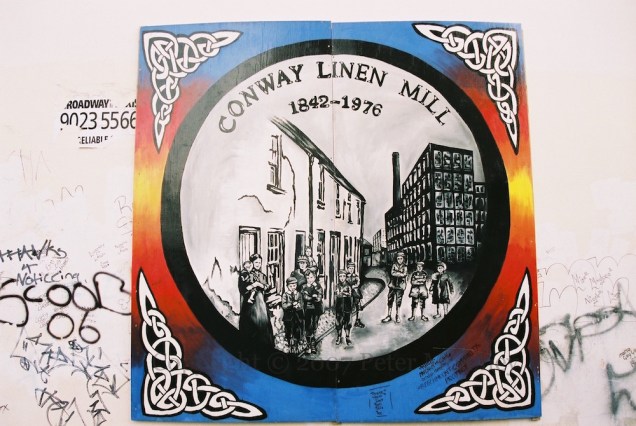

3. Murals on economic (specifically, industrial) life are generally identifiable with the PUL community and generally understood oppositionally by Catholics, on account of the predominance of Protestant workers and owners and discrimination against Catholics throughout the industrial era. The primary PUL symbol of Belfast industry is the cranes Samson and Goliath of the Harland & Wolff shipyards. The construction and sinking of Titanic generally belongs to the loyalist community but there was a H&W/Titanic sinking mural painted in a republican area, at the Giant’s Foot next to Coláıste Feırste (X00661). The only economic theme that appears in republican murals is mill work (M03527 | M04431) though this is not exclusive to republican murals (see M04049).

4. “Community” murals are artworks which depict life in a local community, often in days gone by (i.e. without mentioning the Troubles). We can also include in this category artworks about specific institutions, especially schools, in an area.

Are community murals sectional (i.e. identifiable with a sect)? And if they are sectional, are they oppositional? To repeat, if a piece presents the people or places or history of this neighbourhood, is it (also) a mural about a community belonging to one sect, and to one sect as opposed to the other sect, or is it just an artwork about our area without reference to any sect or any opposing sect? One might argue that a community mural is sectional if that community has a sectional make-up or history, and that anything identifiable with a sect is (at least weakly) oppositional.

In addition to naming communities with single-sect populations or sectional history, community murals often use symbols and emblems that while identifiable with the community are also identifiable with the conflict at large. For example, Linfield or Belfast Celtic are/were local clubs, which local people might celebrate with (local) pride, but they will also have a non-local connotation, which will fortify the community-member with respect to the broader conflict but which a person from the other side will interpret oppositionally. (If the wealthy Malone Road area got community murals, they would perhaps not be oppositional. But of course, the fact that there are no murals on the Malone Road tells you that this area is not in oppositional conflict.)

For the purposes of this page, we include community artworks as sectional, though there are tough cases, such as the Henshaw collages done for the Markets area (an example is included in the ‘Images’ section, below). The use of street artists and street-art styles to paint community murals perhaps pushes them into being non-oppositional; but this doesn’t start happening in significant numbers until roughly 2020 and so is taken up in Visual History 11.

The themes that are non-sectional and non-oppositional, to which each community is just as likely to say “mine”, are …

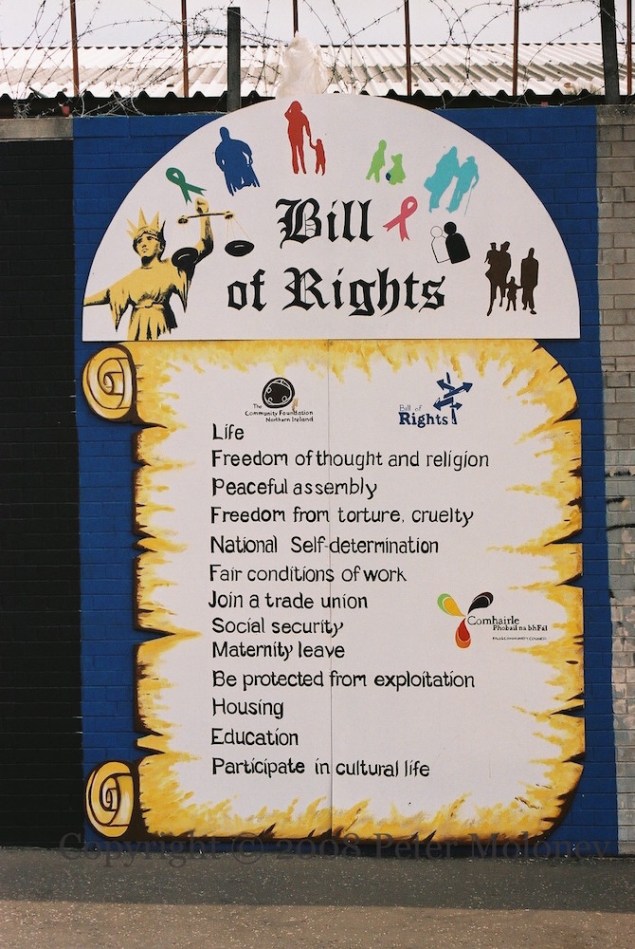

5. Human rights (but be careful that they are not tied to any particular group that we support and they might not)

6. Social issues (such as suicide prevention, anti-drugs; environmental issues; public safety)

7. Women

8. Children (including children’s rights, cartoon and superhero characters)

And finally, there are

9. intentionally cross-community artworks.

(Alongside all of these these we can also include …

Fine Art (there’s nothing preventing fine art from being sectional or from commenting upon constitutional politics or from being on any of the themes listed just above, but in general, fine art tends to be above the fray).

And similarly …

Street art and wild-style writing. As with fine art, nothing prevents street art from being sectional or commenting on politics (constitutional or otherwise) but in general its themes are personal. Street art and tagging/throw-ups/wild-style writing/graffiti art are included in Visual History 11.) )

Interlude over … Back To ‘Re-Imaging‘

Ideally, the state-sponsored re-imaging campaigns would like the art to be completely devoid of sectionality. The loyalist gunmen were initially replaced with sectional cultural, historical, and community murals, and only later was it sometimes possible to deploy only community murals and non-sectional artworks. 2009 appears to be the apogee of re-imaging. (Guns still controversially appeared in memorial murals on both sides.)

A challenge for state programmes is that non-sectional and non-oppositional themes are not as engaging for many people as paramilitary murals, or as cultural, sporting, etc. murals. Indeed, we might (over-)state a general principle: if it’s not sectional (and so, oppositional if viewed by members of the other sect, either in person or on social media), a community won’t bother painting it, only the state (and state-sponsored community groups) will.

Similarly, sectional and oppositional murals are what tourists want to see. At the same time as Troubles-era murals were being passed through the filter of peace, that same peace made it safe for tourists to visit the murals. And – in exactly the same way as just described – the tourists were primarily interested in oppositional murals, and the more threatening (to the locals) the better. This is called “dark tourism” – the visitor achieves the thrill of danger without being in fact endangered – or “conflict tourism” or “Troubles tourism”, in reference to Northern Ireland specifically.

It’s likely that public art in peace-time cannot hope to match the intensity of Troubles art (either for locals or for tourists), and this might be a good thing – the art of peaceful societies should be pleasant and perhaps intellectually provocative or personally enriching, but not aimed at social change and certainly not at change involving distinct communities. The proper comparison-class for state-sponsored art is perhaps art produced by other societies that are not in conflict rather than the murals/artworks currently being produced by communities themselves, much of which is of a piece with Troubles-era art, and it is certainly not the most striking pieces from the 1980s which are heightened by the drama of their time.

Another factor that state and state-sponsored arts programmes have to wrestle with is that they are – in various ways and to various extents — “top-down”; that is, they are spearheaded by outsiders and these outsiders remain in charge or have a controlling interest in the project, no matter the extent to the local community becomes involved.

A related difficulty is that the process often involves outreach to and through community groups and public meetings which can only be of limited reach.

Scholars have not been kind to the state initiatives, the central criticism being that through the re-imaging programmes state organisations attempt to assert control over the visual environment in a top-down manner, such as by bringing in an outside artist to “enrich the community”; in contrast, public art in communities is most meaningful when it is the expression of a community to the outside world or a message from one part of the community directed internally.

Rolston summarizes the re-imaged pieces as being “sanitised, de-politicised” (2012 p. 460); Romens says that the new artworks “fail to depict scenes that resonate with local history and community identity” (2007 p. 12) (the emphasis here is perhaps on “resonate”, as the subject of such pieces is often precisely local history and community); and both Romens and Hill & White (2012) fear that re-imaged artworks will go the way of the Northern Ireland Office/Art College street art from 1977-1981 (discussed in Visual History 11), meaning that while in some cases they are appreciated and in some cases not, in no case do they inspire long-term devotion.

Thus, a more definitive judgement on the state initiatives might be that when the pieces reached the end of their lives they were in many cases replaced by loyalist gunmen – that is, they were re-re-imaged (see Visual History 11) – and additional paramilitary murals were painted.

This page covers initiatives of state agencies. We draw the closing line at 2009 because this is when the first wave of the Re-Imaging Communities programme ended and when two graffiti-art festivals took place on the west Belfast “peace” line — the emergence of aerosol art (graffiti art and street art) is taken up in Visual History 11.

Images

Early (Non-State) Re-Imaging

Some efforts to remove loyalist gunmen were being made locally from 2003 onward. In east Belfast, Rev. Gary Mason worked with local paramilitaries to remove six hooded-gunmen murals, (BBC clarifies that there are six rather than the nine of the CSMonitor | Rolston 2012 p. 453), including

‘UVF Still Undefeated’ (T00147) with footballer George Best (J1969) on the Woodstock Road, and

‘RHC Red Branch Knights’ (J1932 X05517) with local author CS Lewis (J1919) in Ballymacarrett.

Other local initiatives took place in Craigyhill (Larne) (though there was a setback in The Factory (Larne) & Ballycarry) and in Bangor. (Lisle 2006, p. 51 n. 41.)

McCormick & Jarman 2005 note the following early changes:

In New Mossley, Newtownabbey, a YCV gunman was replaced by an environmental artwork (BelTel article);

in Monkstown, Newtownabbey, a UVF mural with four hooded gunmen aiming at the viewer (J1042) was replaced by one of Edward Carson’s statue outside Stormont, though the names from the previous mural (John Webber/Webster and Lee Irwin, son of John Irwin) were retained (and, as shown below, Steven Cook’s name was then added):

in Linfield Road (south Belfast) a UFF mural …

… was replaced by an Orange Order parade against the backdrop of Sandy Row …

… which itself was later replaced by a children’s artwork:

In 2004, the East Belfast Historical & Cultural Society sponsored a series of fourteen panels in Thorndyke Street, chronicling Protestant history from Cromwell to Cluan Place; the centrepiece is below. (Previously (2003) from EB Historical & Cultural Society McCurrie & Neill memorial garden M02366 | later work: M03498 | M04069 | M04840.)

State Re-Imaging

A 2.4 million pounds, lottery-funded, “Art Of Regeneration” programme was announced (in February 2004) by the Arts Council in conjunction with the NI Department of Culture, Arts & Leisure, distributing money to Borough Councils (Craigavon, Derry, Moyle, Ballymoney, Antrim, North Down, Strabane, Fermanagh, Newtownabbey – 85% of funds allocated outside Belfast).

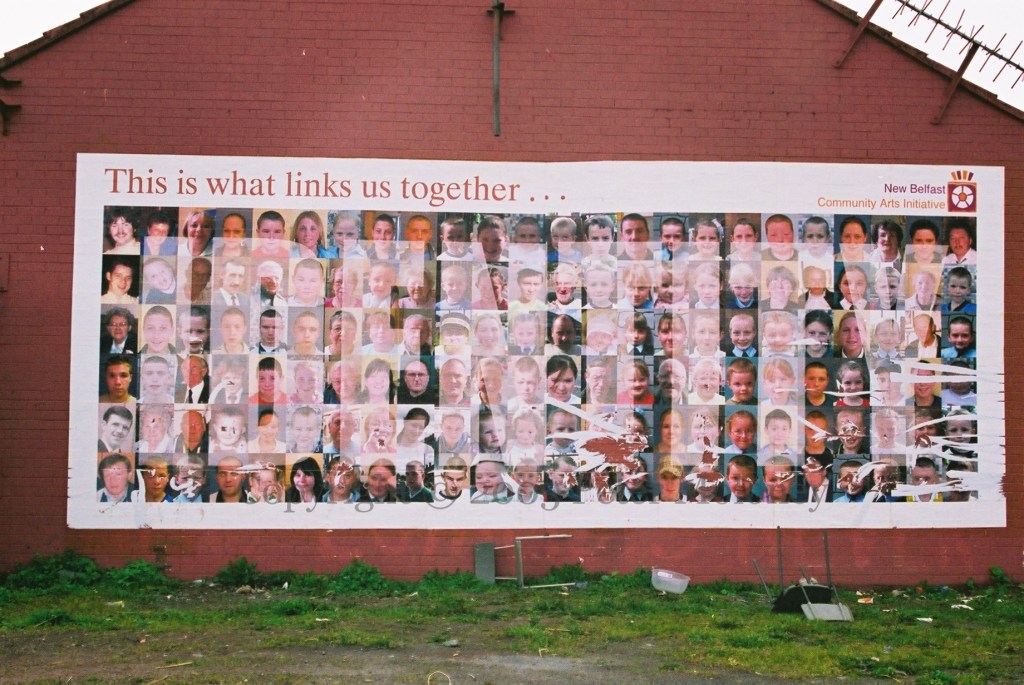

Many of the sponsored projects concerned other forms of art — here is an account of a sculpture supported by Ballymoney Borough Council [link is dead] — but there was funding for new artworks via the New Belfast Community Arts Initiative — an organisation formed in December 1999 to promote community arts activities (A Coming Of Age). In the (CNR) Short Strand, an Éıre mural with local activists was replaced in 2005 by a board celebrating “identity”; it in turn would be quickly replaced, in 2006.

Another New Belfast artwork, which did not replace a previous mural, in the (CNR) Markets area: “Women of substance – Plúr Na mBan”.

In Tullycarnet in 2005, an Eddie The Trooper mural (see Eddie’s Visual History page) was replaced with a mural to (Catholic) WWII Victoria Cross recipient, James Magennis. According to McCormack (J2592) the mural was organised by the Tullycarnet Action Group Initiative Trust with funding from the Community Relations Council which was later (2006 onward) involved with the Re-Imaging Communities programme. It is not known if the Magennis mural was part of the Art Of Regenation programme or a pre-cursor to the Re-Imaging Communities programme.

2006’s ‘Re-Imaging Communities’ programme brought together the Arts Council (which oversaw the project), Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister, the Department for Social Development, the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure, the International Fund for Ireland, the Northern Ireland Housing Executive, the Community Relations Council, and Solace (the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives and Senior Managers), but not Belfast City Council (Rolston 2012 p. 454). The SDLP’s Alban McGuinness suggested the programme amounted to “a polite form of extortion” on the part of loyalist paramilitaries (NewsLetter). Despite its name, Re-Imaging Communities was, like other initiatives, a mix of new art and replacement art.

The Housing Executive formed (in 2004) a ‘Community Cohesion Unit’ which later joined together with Belfast City Council’s ‘Greater Belfast Mural Project’. Rolston states that the Housing Executive is the “biggest influence” on the transformation of murals (Rolston 2012 p. 453). In 2007 and 2008, the efforts of the joint group collaboration oversaw the re-imaging of UDA murals in the Village, south Belfast. In 2007, these hooded gunmen were replaced by an image of Queen Elizabeth:

And in 2008 the Eddie The Trooper mural was replaced with a large painting of King Billy:

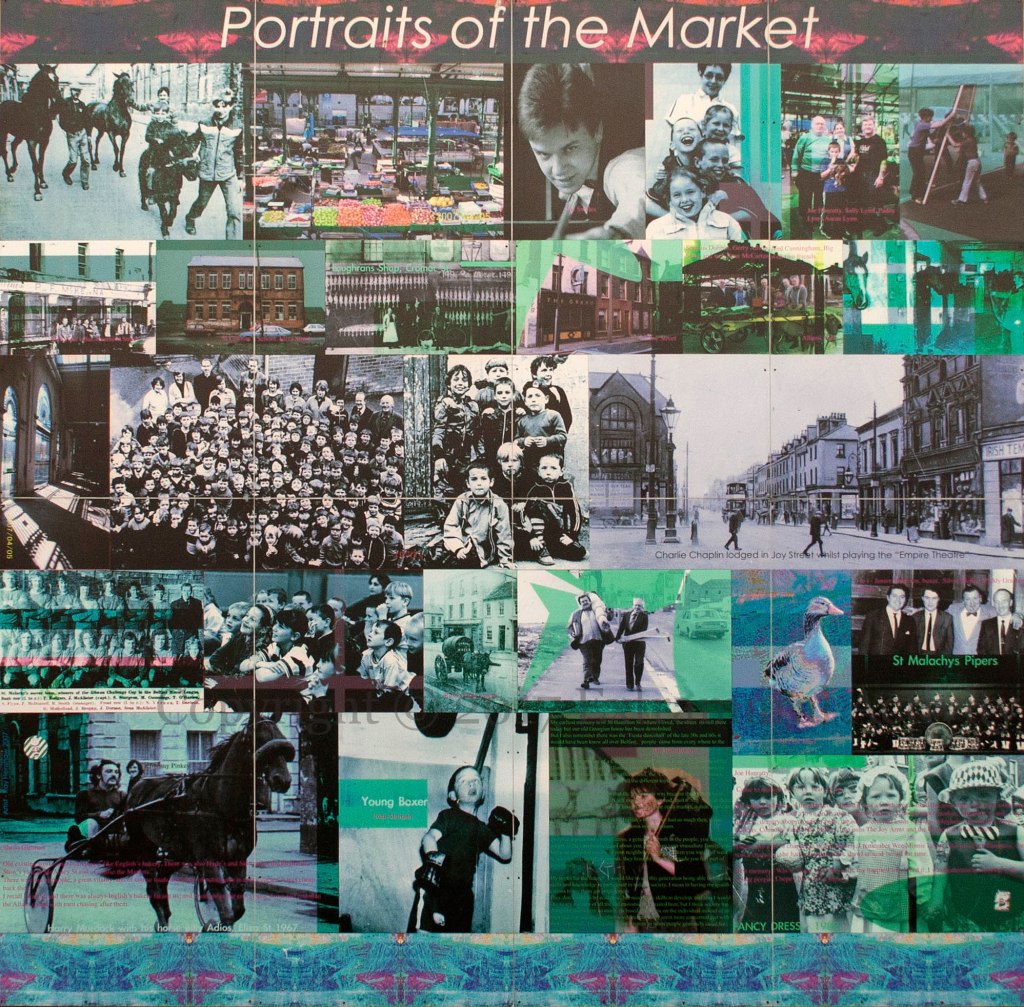

The series of five boards in 2008 about the (CNR) Markets area done by artist Raymond Henshaw is a good example of an especially anodyne type of community mural/artwork, where the community is shown in “the good old pre-Troubles days”. These large boards collated photographs from yesteryear on the themes of Portraits (shown below), Industry, Social History, Sport & Culture, Bars (and a sixth wall showing people). The project was funded by the Arts Council and locally involved the Markets Development Association. (In 2009, Henshaw produced a series of tarps for the fencing around a vacant lot on the Shankill as part of the City Council’s Arterial Routes programme.)

In Glenbryn (north Belfast), a mural putting the Confederate forces of the American Civil War (which it calls the “War Of Northern Aggression”) in parallel with the resistance to Home Rule was replaced in 2009 (under the (second) Re-Imaging Communities scheme) with an artwork of famous faces from the past, designed in collaboration with older residents.

In Kilcooley (Bangor) a UDA mural with a gunman aiming straight at the viewer was painted out and later (2009) replaced by a mural to local Victoria Cross recipient Edward Bingham.

A similar project occurred in Loughview/Redburn in Holywood. These two were locally organised by North Down council’s 2004-2009 programme called “Art Of Regeneration” (Hill & White 2012) – we guess that North Down did not want to cause confusion by changing the name of its existing programme to “Re-Imaging Communities”.

The Re-Imaging Communities projects (both the initial 3.3m from 2006-2008 and the .5m in 2009) was the most intense period of re-imaging. According to this Scotsman article, the first wave of re-imaging involved 105 murals; the 2009 Evaluation Report of the second Re-Imaging Communities project claimed that by the summer of 2009, 39 projects involving murals had been completed, including further work in lower Shankill, where six murals were replaced …

Drumcree by Shankill A-Z – both shown below

UDA Scottish Brigade (C01463) by ’69 Gold Rush (X00298)

Siege of Derry (M03808) by Shankill Road Boxing (M05059)

Can It Change (M03801) by Play (X00308)

C Coy (M02480) by Shankill 455 AD (X03426)

Ethnic Cleansing by Everybody Has The Right To Participate (both shown below) –

… and four new murals added:

Martin Luther (X00301; see also M02382) and

three in Dover Place: Enlisting in WWI (X00504) – WWII Blitz (X00502) – WWII VE Day (shown below).

Also in the lower Shankill by this time were murals about Cuchulainn (shown below), the Red Hand Of Ulster (X00309) which replaced the C company mural shown above (X00075), and the Battle Of Talavera (X00325). (2009-06 BelTel article on the changes.)

One of the 2008 murals: Cuchulainn, defender of Northern Ireland, who replaced the Stevie ‘Top Gun’ McKeag (X00068).

One of three new murals in Dover Place: VE Day.

It is (again) worth noting that while some of the murals being replaced were paramilitary murals (e.g. UDA Scottish Brigade replaced by ’69 Gold Rush), some of them were “cultural” rather than paramilitary, but that they were replaced anyway, by murals/artworks that are “community” or entirely neutral in theme. For example, the Siege Of Derry mural was replaced by one about Shankill boxing; Drumcree was replaced by the Shankill A-Z; the Shankill Eddie had already been re-imaged into Can It Change? (about the house-burnings in Bombay St) and this in turn was replaced by a kids’ piece. In east Belfast, a H&W shipbuilders mural (J1913) was replaced by a cross-community poem No More in 2010 (X03411).

It can be seen from these changes that the funding agencies prefer images that are, as much as possible, not identifiable with one community or the other, on themes such as the local community (in the good old pre-Troubles days) and global issues such as children’s and human rights. For example, in Ardoyne, a Sean McCaughey mural was replaced by a mosaic of children’s faces and a hunger strike mural was replaced by one for the Fleadh.

Agencies were not always successful in getting a non-sectional image put in place. Rolston (2012 p. 455) reports that the Arts Council thought King Billy was too divisive an image to replace the Village Eddie (both shown above), but lost this particular battle. Rolston (2012 p. 459) describes how the Arts Council demanded the removal of a sword in the hand of the chieftain on the right of the Flight Of The Earls mural in Ardoyne; instead, he was painted clutching the collar of his cloak.

At the same time (Rolston continues), funds were allocated to murals with WWI soldiers carrying weapons at the Somme. His explanation is a double-standard on the part of the Arts Council: “The demarcation line between militant republicanism and the state is rigid and cannot be transgressed, even artistically. But that between militant loyalism and the state is more porous, allowing official and illegal iconography to coexist, even if not acceptable to all.” Why the Arts Council should decide in this way is unknown; it was perhaps willing to go make greater compromises in the case of loyalist murals in order to get rid of hooded gunmen.

Also worth noting are the range of artists involved: the lower Shankill re-imaging of 2009 involved a street artist — VERZ/Tim McCarthy (’69 Gold Rush, Luther), along with studio artists Ed Reynolds (Play, Right To Participate) and Lesley Cherry (A-Z, Boxing), and graphic designer Steven Tunley from New Belfast/Community Arts Partnership (Original Belfast and the three Dover Place pieces).

Before: Shankill Rd Supports Drumcree

After: Shankill A-Z by Lesley Cherry

Before: Can It Change?

After: Play by Ed Reynolds

The info board for Play described the history of the wall (including the Adair-era Eddie mural) and also shows the involvement of the Lower Shankill Community Association.

Before: “Ethnic Cleansing”

After: “Everybody Has The Right To Participate” by Ed Reynolds, shown here with pallets in rows for inclusion in the 11th night bonfire.

Memorial Murals & Stones

Like their republican counterparts, memorials to loyalist paramilitaries continue to appear and in the case of the UVF – due to the shared name – sometimes appear alongside the Ulster Volunteers who fought in the 36th Division in WWI. (The UDA would eventually also adopt WWI as a precursor.)

This Rathcoole mural (from 2004) includes both portraits of six modern-day UVF volunteers (in the apex) and four columns of WWI dead (along both sides).

In the memorial garden in Kilcooley, Bangor, which cost 74,000 pounds, the recessed panels beside the gate and in the back wall are of WWI, while the three standing stones – added after completion – are to UDA, RHC, and UVF volunteers.

Similarly, plaques to contemporary volunteers were added below a Thiepval Tower board in Pine Street.

The Platoon 5, A Coy, 1st Batt UVF mural in Northland Street was re-imaged with a Thiepval Wood mural, but a stone was added to the UVF volunteers who died “not in the mud of foreign lands/Nor buried in the desert sands”:

This RHC mural and plaques was in the old Hunt Street, east Belfast. It was later joined by a memorial garden mixing WWI and modern RHC (M04845).

Stepping back from re-imaging and considering PUL muraling generally, within the broader categories listed in the Introduction, the most popular new themes for loyalist murals in this time-period were …

… the mobilisation against Home Rule in 1912: Edward Carson, the Covenant, and also the Clyde Valley gunrunning (M02446 | Rex Bar M02452 M02453 M02454 | Londonderry M03584 | Portadown M04155 | M04205 Village | M04282 Shankill | M04854 | M04961 | M05397 | M05688 | 2010 M05773)

… WWI: the 36th (Ulster) Division, the Battle Of The Somme

… WWI VC recipients (2001 M01520 M01515 | 2003 M01930 M01925 | M02336 etc | M02445 | M03061 | M03076 | M03505 | M03903 | M04186 Donegall Rd bridge | M04281 | M04913 | M04930 | M05342

… WWII VC recipients: Magennis VC (see above) | Bingham VC (see above) | also Seymour Hill In WWII

… soccer: George Best was a favourite of funding agencies because his time at Manchester United and world-wide prominence made him a candidate for a non-oppositional figure, even though he played for Northern Ireland at the international level (and, he had just died in 2005, which meant he could be eulogised and much of his controversial past put in perspective). Thus, he generally appeared in loyalist areas – e.g. Blythe St (shown below) | Portadown (shown below) – the only exception being that his name was included in a ‘welcome’ artwork in the New Lodge (WP).

NI Football (M03499 | M03638 | M04203 | M05824 Sandy Row | M07752 Broadway | Times Bar (shown below)).

Local and Scottish teams. Local soccer is semi-professional, so fans also follow Scottish and English teams. Of Scottish teams, the favourites are the two Glasgow teams, Rangers (supported by loyalists) and Celtic (supported by republicans).

The George Best mural in Blythe Street replaced the UVF/Deuteronomy mural (M01515).

The George Best mural in Brownstown Road, Portadown, replaced a Billy Wright mural (J0320).

Linfield won seven trophies in 1961-1962. It is perennially the strongest local team. This board is on the Shankill in west Belfast but the pitch is east of the Motorway.

Glentoran is the east Belfast rival of (south Belfast’s) Linfield.

Rangers ‘Ready’ mural in Portadown.

“The Ulster Connection” – this east Belfast mural lists local players who have played for Glasgow Rangers.

Scottish League and Scottish Cup champions, 2009, riding to victory like King William at the Boyne. King Billy, or at least his horse, serves as a vehicle for the hero of the day – see also King Michael Stone.

Smaller and not-particularly-successful teams serve only the functions of local rivalries or even just local pride, such as Albion Star in the (Belfast) Markets (X09064) or the local (Derry) Brandywell clubs (X02831). A mural to the former Belfast Celtic would appear in 2009 (M05784 | X00386) and one to the current Donegal Celtic in 2010 (M07959 | X02888).

… UK royalty.

Here is another image of the youthful Queen Elizabeth II in the Village (south Belfast):

… industry: Harland & Wolff shipyard, where Titanic was built: M03125 shown below | M02332 shown below | Downing St replacing a UFF 2nd Batt C Coy mural (M05371) | shipyard workers in the style of William Conor 2013 dating to at least 2008 X01159 | Ship Of Dreams replaced the Democratic Rights mural in Kenilworth Place/east Belfast 2010 M06834. H&W/Titanic would continue to be a frequent theme of murals in the 2010s, and even appeared in republican west Belfast (2012 X00661).)

The only economic theme that appears in CNR murals is mill work (M03527 shown below | M04431) though this is not exclusive to CNR murals (see e.g. M04049).

Additional Ulster-Scots murals were painted. See Visual History 08 for the introduction of Scots-Irish/Ulster-Scots murals in 1999 and the separate page on Ulster-Scots Murals for the later murals.

Hooded Gunmen Persist

Despite these attempts at re-imaging and the emergence of additional themes, many murals of loyalist hooded gunmen continued to exist and to appear anew.

Near the Carson mural shown above, for example, one could find several UFF murals, such as this one:

And within a year of the Magennis mural (shown above) replacing the Eddie The Trooper mural in Tullycarnet, this UFF mural was added adjacent to it:

This “UFF Dee St Coy” hooded gunmen mural was in east Belfast. It survived until 2019, when it was replaced with another UDA mural.

See also:

combined Somme and UVF/RHC (M02367) – compare with (republican) Twinbrook mural combining 1798, 1916, and PIRA (M01635) | Freedom Corner (M02371) | Templemore Ave (M02385) | Young Newton (M02386) | Tullycarnet UFF (M02937 )| M03011 | M03022 | M03027 | M03038 | M03059 Cloughfern Eddie | M03060 Cloughfern UDA | M03071 | M03075 would be blanked but then M03701! | M03087 | M03097 | M03378 | M03710 Kilcooley (reimaged?) | M04128 | M04953 | M04982 | M05007 | M06591 Spike & Tom

See Visual History 11 for the resurgence of loyalist gunmen – a phenomenon we call “re-re-imaging”.

See also ‘Dark Tourism’ below.

Non-Sectional & Non-Oppositional Artworks In Republican Areas

UN Day For The Eradication Of Poverty (Dunlewey St). The artwork makes reference to child poverty in “W. Belfast” which would include the (loyalist) Shankill and Woodvale areas. However, the Celtic imagery will serve to limit the domain of care to CNR west Belfast.

“Death drivers are killing the community” (Ascaıll Ard Na bhFeá/Beechmount Avenue)

Bill Of Rights (Northumberland St)

Dark Tourism

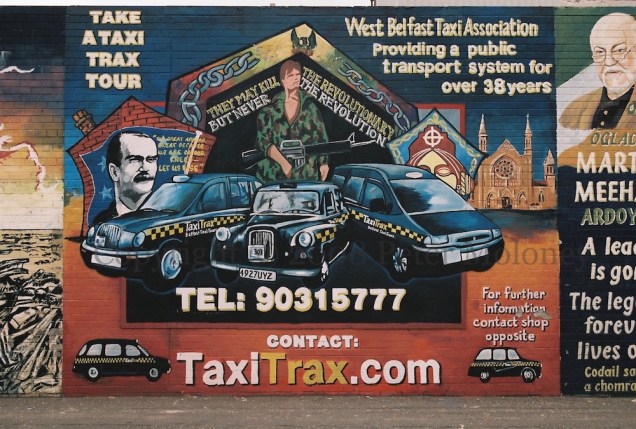

The ceasefire (1994) and the Good Friday Agreement (1998) meant that tourists could feel safer in Belfast and London-/Derry. As early as 1999, Fáılte Feırste Thıar was taking advantage of the peace to promote nationalist west Belfast as a tourist destination (BBC). Murals and other reminders of the Troubles such as the “peace” lines have proven a popular attraction and are included as a part of every tour, whether offered by Taxi Trax, Belfast Black Cab Tours, Coıste (whose tours guided by former prisoners) or even the broader City Sightseeing Belfast tour, which includes the Falls and Shankill and a stop at the so-called International Wall. Also on the tour is the Cupar Way part of the (so-called) “peace” line that divides CNR and PUL west Belfast. Tourists are now encouraged to leave a signature and a message in permanent marker on the wall. They leave messages of hope and love but it’s also likely that they get a thrill from the loyalist gunmen and, perhaps to a lesser extent, from the historical images of violent struggle elsewhere on tour.

West Belfast Taxi Tours. Only one of the murals depicted was in fact still visible in 2003.

Derry Sightseeing Bus featuring Free Derry Corner and The Petrol Bomber mural.

Murals are included in Fáılte Feırste Thıar’s advertising to tourists.

(Compare the images above to a 1985 nationalist mural (M00311) ironically using the Tourist Board slogan ‘Discover Ireland’ and to a loyalist one (A009) using the slogan from the post-peace campaign “Wouldn’t it be great?”)

On to Visual History 11.

References in parentheses to mural collections:

M = Peter Moloney Collection – Murals

T = Paddy Duffy Collection

X = Seosamh Mac Coılle Collection

Back to the index of Visual History pages.

Copyright © 2018-2025 Extramural Activity. Images are copyright of their respective photographers.