Introduction

In politics, those who want to go to war are called “hawks” while those who pursue diplomacy are “doves”. (The terminology goes back to the War Of 1812 between the USA and Britain – JSTOR Daily – or to the Cuban missile crisis – New Republic.)

There are no actual hawks, with sharp beaks and talons, used in murals to represent the paramilitary activity of republican groups during the Troubles. Instead, volunteers and their weapons are portrayed and, in terms of metaphorical birds, the phoenix and the lark stand in for the hawk. The phoenix in (pre-Agreement) republican muraling symbolises the (Provisional) IRA and harkens back to the 1916 Rising, while the lark is an image used by Bobby Sands and represents political prisoners, and both can be used to symbolise resistance generally.

It is well known that at the time of the ceasefire and the peace process – 1994 to 1998 – paramilitary images disappear from republican murals. While there are still images of historical figures bearing weapons, both from the Troubles and before, there are no longer any “hooded gunmen” murals, that is, no images of active IRA volunteers on manoeuvres or images glorifying their weaponry. Here is Bill Rolston (“Re-imaging: Mural Painting and the state in Northern Ireland”, International Journal Of Cultural Studies 15.5, 2012, p. 451): “on their own initiative and without any state funding republicans removed the guns and masked men from their murals. From that point, the only guns to be found in republican murals were in memorials to dead comrades or in murals on historical themes.” This thesis was tested perhaps by only one mural, (included below,) painted in the Markets area of Belfast, and this might date to the break in the ceasefire.

It’s also worth noting that at the same time as the gunmen and their guns disappear, the lark and the phoenix disappear from republican murals. During peace talks one might expect the phoenix to disappear, on account of its close association with the IRA. But since there were republican prisoners until their release after the Good Friday Agreement (in batches from October 1998 to July 2000), one might expect the lark to continue to fly. Instead, however, the dove is used to symbolise the plight of current prisoners and the importance of their release to the peace process. The dove, whose basic meaning is peace, promises to set the prisoners free, often flying with a set of keys in its mouth. This freedom can only come about because the struggle of the prisoners has ended, and so the lark, in its original meaning of resistance, is no longer suitable.

After the peace process the dove disappears and the lark and the phoenix return to murals, but they symbolise historical volunteers and historical prisoners, those who lived and died before a negotiated peace was contemplated by republicans. Indeed, since republican prisoners are released as a result of the Good Friday Agreement, the lark can only bear a commemorative meaning.

So strong is this association between the lark and the non-conforming prisoners before the peace process that murals from relating to prisoners after the peace (from so-called “dissident” groups) do not use the lark to represent prisoners but only barbed wire.

This page documents, in historical order, the murals featuring the phoenix, lark, and dove, and attempts to make the case for the theses above. The decades can be divided up into three time-periods: pre-ceasefire, ceasefire, and post-Agreement. The nine sections below fall within these time-periods as follows:

pre-ceasefire

the Bloody Sunday dove

the “caged” lark, symbolising political prisoners

the “lark of war”, symbolising armed resistance

the phoenix, symbolising resistance, typically armed resistance

ceasefire/peace process

the dove, symbolising the demand for the release of prisoners

post-Agreement

the dove, post-Agreement

the “memorial” lark

non-use of the lark by anti-Agreement republicans

the phoenix as symbol of both historical and modern-day anti-Agreement republican

Images

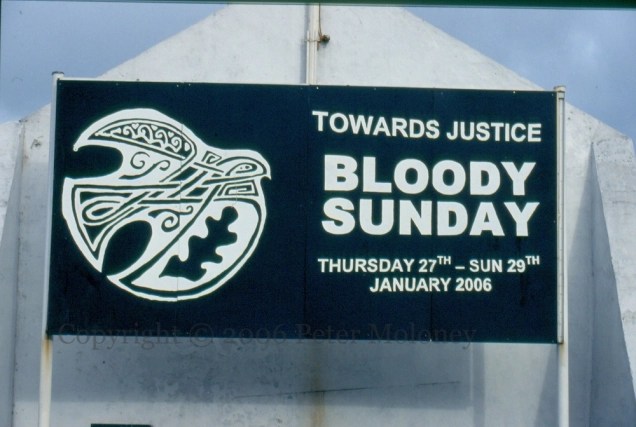

The Dove (Bloody Sunday)

The dove is an internationally recognised symbol of peace, an image borrowed by the early Christians from the Old Testament story of Noah’s Ark, in which it symbolises the relenting of God’s wrath, and from the New Testament’s likening of the holy spirit to a dove at the anointing of Jesus of Nazareth.

The dove has been used as a symbol of Bloody Sunday, beginning with the memorial raised in Derry in 1974. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was a non-violent resistance organisation, advocating for equal rights for Catholics by means of marches and peaceful protests. On January 30th, 1972, British Army soldiers killed 13 people at a civil rights march in Derry (with another dying later). The dove and not some image of violent resistance such as a fist or gun is used because the civil rights protests were themselves non-violent, even though Bloody Sunday (and the riots of August 1969 in both Derry and Belfast) effectively transformed the struggle into a military one.

The dove was incorporated into the official symbol for Bloody Sunday, an abstract dove in Celtic knotwork, including the oak leaf as a symbol of Derry. Here are three images, one from before and two from after the peace process.

The “Caged” Lark (pre-Agreement)

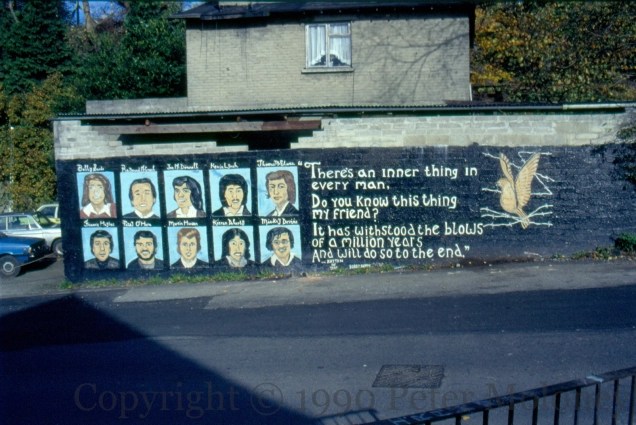

The lark is a widely associated with daybreak (“up with the lark”) but its meaning in Irish republican murals is different. The image comes from Bobby Sands’s 1979 An Phoblacht/Republican News article, The Lark And The Freedom Fighter, in which the lark refuses to sing when it has been caged, no matter how much this is demanded by its captors. In Sands’s analogy, Irish republicans, and captured volunteers in particular, are like the lark. They have lost their freedom to British domination and to the cages of Long Kesh, and their response to this imprisonment is resistance. Sands writes, “I refuse to change to suit the people who oppress, torture and imprison me, and who wish to dehumanize me. I have the spirit of freedom that cannot be quenched by even the most horrendous treatment. Of course I can be murdered, but while I remain alive, I remain what I am, a political prisoner of war, and no one can change that.” The lark is thus a symbol of republican political prisoners and especially the “non-conforming” prisoners, those on the blanket, the dirty protest, and the hunger strikes. (For this reason, the lark is predominantly shown in barbed wire.)

The mural below does not contain an image of a lark, just the title “The Lark And The Freedom Fighter” along with Sands’s portrait and the barbed wire of prison.

In this mural, both the lark and Ireland are wrapped up in barbed wire.

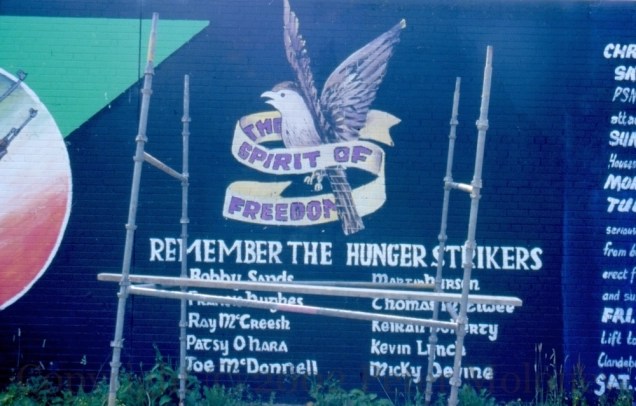

The lark with a list of the ten deceased 1981 hunger strikers.

The lark (and the phoenix – see next section) as symbols of resistance in Andersonstown.

(See also 1981 DS1r 061 in AMCOMRI Street, Belfast.)

“We have the spirit of freedom” in Bishop Street, Derry.

“Towards liberty” in Enniskillen – probably the only use of this phrase.

Strabane

The lark is placed in parallel with the eagle as a symbol of Native American aspirations. Whiterock Road, Belfast.

This unentangled lark – representing the resistance of the republican community generally – is appropriately accompanied by Sands’s remark that everyone has their part to play in the struggle.

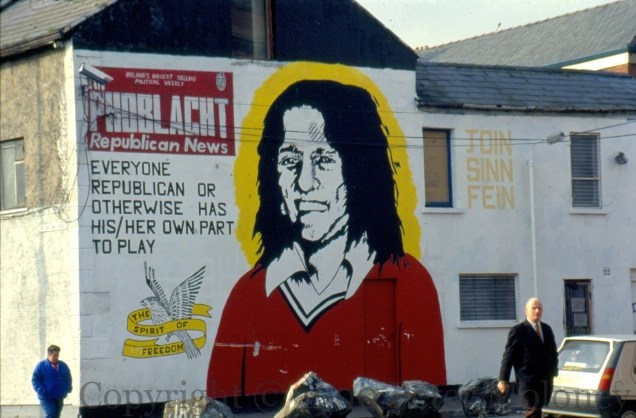

In this mural, the verbiage and the armed volunteer to the right, indicate that the support of the people – the “spirit of freedom” lark – includes support for the military campaign.

The Lark Of War

There are two types of pre-Agreement lark: the “caged lark” which is bound in barbed wire, and the “lark of war” as it sometimes appears with an assault rifle (and with or without barbed wire). This second lark might also be called the “lark of freedom” for it frequently appears alongside this word, but “freedom” here means “freedom from British rule”.

(During the peace talks, the dove also appears with with the word “freedom” and very often the Irish “saoırse” but in this later period it means “freedom for prisoners”. The post-peace lark we call the “memorial lark”. There is some overlap between this page and the page on Electoral Murals, which (among other things) charts the emergence of the word “peace” in electoral pieces.)

“We [IRA] Are Here To Stay” in Islandbawn Street, Belfast. The “1919” on the left was later changed to 1916.

A lark of war, with barbed wire, in Andersonstown, west Belfast.

The barbed wire is missing and the lark is in free flight (and looking pretty angry). Ballycolman, Strabane.

Also from Ballycolman, Strabane.

This Newry image of a lark of war is from 2001 – post-peace – but is clearly quite a bit older. Please get in touch if you have an earlier date.

The Phoenix (pre-Agreement)

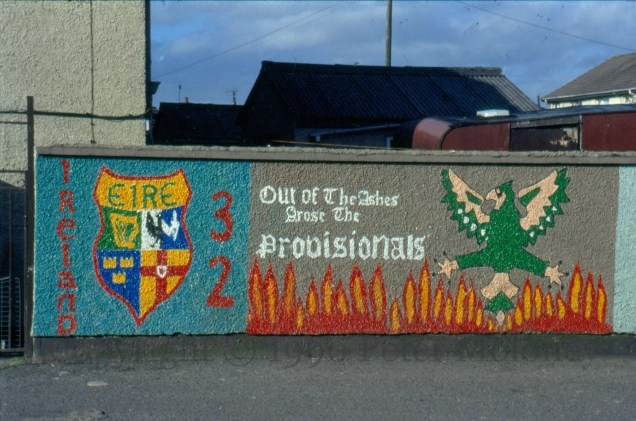

The phoenix is a symbol of rebirth after death. It is used in republican murals to symbolise the Provisional IRA rising out of the ashes of the (Official) IRA and the riots of 1969. But since muraling does not begin until the second hunger strike in 1981, it is also used to symbolise the resistance of the prisoners.

“Out of the ashes arose the Provisionals” in Derry.

The same in Strabane. (There was a mural in Andersonstown, Belfast with Phoenix and “Out of the ashes that was Belfast came the Provos” – see R91086.)

IRA volunteer with RPG. Andersonstown, Belfast.

Lenadoon, Belfast.

Strabane.

Phoenix with Tricolour and Sunburst flags (used as symbols of the IRA and Fianna (youth IRA). Creggan, Derry.

The phoenix in Anne Street, Derry (which has survived untouched since 1981) appears alongside the Tricolour, Starry Plough, and Sunburst flags.

The phoenix used not by the IRA but the INLA in Strabane.

The symbol of the phoenix is applicable to deceased volunteers. This IRA roll of honour was in Derry.

Dead volunteers (in this case, Willie Fleming and Danny Doherty) will persist in the form of their comrades: the funeral volley over their coffins confirms that thir struggle continues. Chamberlain Street, Derry.

A generic funeral volley on Rossville flats, Derry.

The military resistance has a precedent in the Easter Rising of 1916. This mural was in Beechmount Avenue, Belfast.

The Easter Rising phoenix on the Whiterock Road, Belfast.

The most famous act of resistance is the 1981 hunger strike. In this Shantallow, Derry, mural, a board to the hunger strikers has been added above a IRA phoenix.

The phoenix in Clowney Street (Belfast) was first painted in 1981 and persists to the present day. (See The Oldest Murals for its history.) Here is represents the struggle of both “the people” and the 1981 hunger strikers.

The desire for “saoırse” (“freedom”) rising from the death of Bobby Sands in Twinbrook, Belfast.

Repeated from the section on the lark, above, this time for the phoenix in the centre, symbolising the struggle (specifically by the first six deaths of the hunger strike) to break the H-Blocks – “a nation once again”.

An abstract phoenix holding a ribbon bearing the first names of the first six hunger strikers: Bobby, Francis, Patsy, Raymond, Joe, Martin – IRA (Tricolour) and INLA (Starry Plough) hunger strikers.

The ten deceased 1918 hunger strikers (left) and a list of the prisoners’ demands (right). Creggan, Derry.

Finally, the phoenix can be used for the struggle in general, more broadly than either paramilitary efforts or the hunger strike.

This small phoenix is combined with a pair of Tricolours and “Free Ireland” suggesting that the phoenix is the resurrection of Ireland from British rule. The Tricolours are on pikes, symbolising the 1798 Rebellion.

“Eire [Éıre] Nua” – New Ireland.

The phoenix and the Mexican eagle symbolising anti-colonial struggle in two nations.

The Dove (peace process)

Although its primary meaning is to represent political prisoners, the lark stands for resistance generally and, in the lark of war, the armed struggle. Even as a symbol for prisoners it has connotations of militarism, as many prisoners were incarcerated for their roles in IRA and INLA activity. These militaristic connotations bring it into tension with the dove as symbol of peace. It is not really possible to employ both at once: even if tied to two different dimensions of the republican struggle – the military and the political – the stated goal of militant republicanism is the singular one of a united Ireland, a goal that would not be understood as peaceful by Protestants, and which is different from the meaning of “peace” immediately available to all factions as the cessation of paramilitary violence.

Thus, when the dove first appears in Sınn Féın murals – that is, in murals encouraging people to vote for Sınn Féın – and sometimes alongside the word “peace”, it indicates the beginning of a move away from the violence of the IRA and towards a political settlement. Sınn Féın and the IRA are often spoken of in one breath and in murals the Sınn Féın name or logo did sometimes appear in the context of militaristic imagery. But beginning in the late 80s, Sınn Féın and the political arm of republicanism is associated with the word “peace” and the image of the dove and is thus in tension with the militaristic murals which were so familiar up to that point. In other words, where previously political power had been a means of demonstrating support for the military campaign, it now included the suggestion of an end to the armed struggle. (Had this been foreseen, one might indeed have objected when Danny Morrison said, “Who here really believes we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland?”) In short, the promise of peace gradually (from 1989 to 1994) put the armed struggle into second place.

Images of doves as standing generically for the peace process are presented first in this section, followed by the dove as freedom for prisoners specifically.

This dove – here looking more like a gull – carries a tricoloured ribbon and promises “Freedom, justice, peace” is repeated. Ballycolman, Strabane.

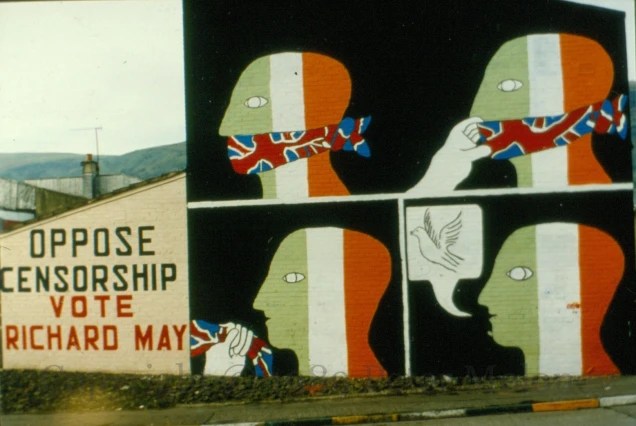

In this Springhill, west Belfast, mural, there’s no explicit reference to Sınn Féın, apart from the call to vote for their candidate, Richard May, in City Council elections. But the issue of “censorship” will immediately be understood as a reference to the Broadcasting Ban, put in place in 1988, disallowing Sınn Féın representatives from speaking in their own voice on television and radio. The dove emerging from the mouth of the tricoloured head speaks the language of peace – symbolised by the dove – suggesting that there is some for negotiation on the (violent) removal of British forces and administration.

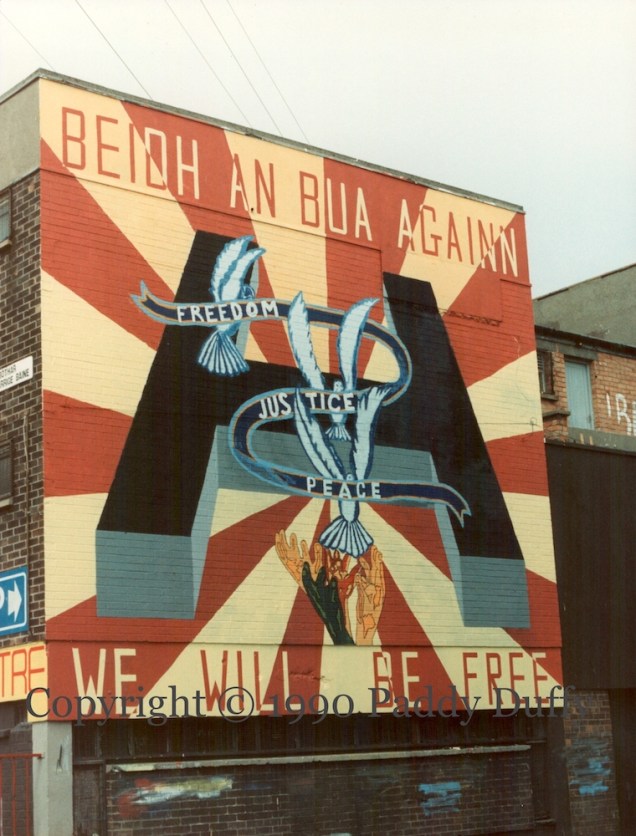

Doves are released by hands in the colours of humankind over the H Blocks – all the world wants peace, it seems. In contrast, the words say “Victory will be ours” (Beıdh an bua agaınn) and “We will be free”.

Cormac cartoon rendered as a mural on the Whiterock Road, Belfast.

This board is in Letterkenny, in the Republic Of Ireland. On the left is a dove with a tricoloured ribbon; on the right is Cormac’s cartoon.

“Who Really Wants Peace?” A dove with olive branch is shackled by a British ball-and-chain. New Lodge, Belfast.

This is a Great Hunger mural (An Gorta Mór) but its ancillary symbols are a reflection of its time: at the top, a dove; at the bottom, a green ribbon, symbol of the campaign to release political prisoners. (For more on the green ribbon campaign, see Visual History 07.)

This New Lodge mural is otherwise unknown, which is very unfortunate, as it (and the tree mural in the background?) appears to represent be an early (1988?) example of a non-sectarian mural expressing the desire for peace in a republican area.

This is the sole paramilitary mural from the years of the peace process, with hooded gunmen, Tricolour and Sunburst, and phoenix. It perhaps was produced during the break in the ceasefire. Once painted, it was allowed to persist beyond the Agreement into (at least) 2001. In Stanfield Place in the Markets, Belfast.

The dove stands for the peace process generally, but its most interesting use is in connection with political prisoners. The campaign to release prisoners got under way immediately in the process, i.e. 1994.

This dove is a fist that smashes the chains holding “700 Irish political hostages”.

Another mural associating broken chains with doves, in Chamberlain Street, Derry.

This dove, on the railings outside the IRSP/INLA offices on the Falls Road, takes the place that a lark traditionally would against a background of barbed wire. Where “saoırse” would previously have meant freedom from colonial oppression by means of violence (and the elevation of the Irish language), it now means that peace is the key to the freedom of prisoners – the dove holds the keys.

The image of a dove carrying keys was a popular one. Here it is on the New Lodge Road:

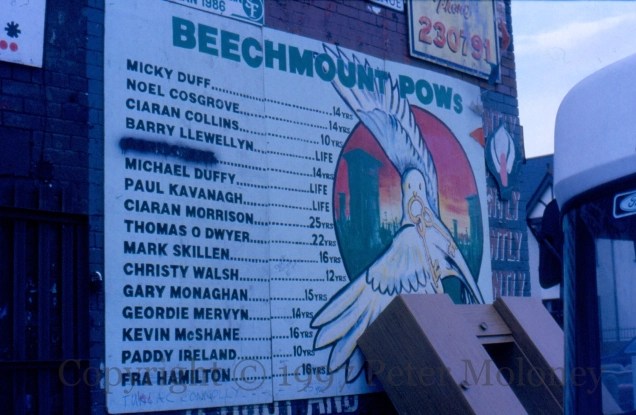

And in Beechmount:

And in Letterkenny, Republic Of Ireland:

This mural in St James’s is unusual in that in the lark is included in the apex of the mural when the dove is already present in the central panel of the piece:

This bird is somewhat ambiguous in nature. It is next to a saoırse/green ribbon mural (1995 M01241) which suggests a dove, and it is white which suggests a dove, but its plumage suggests a lark.

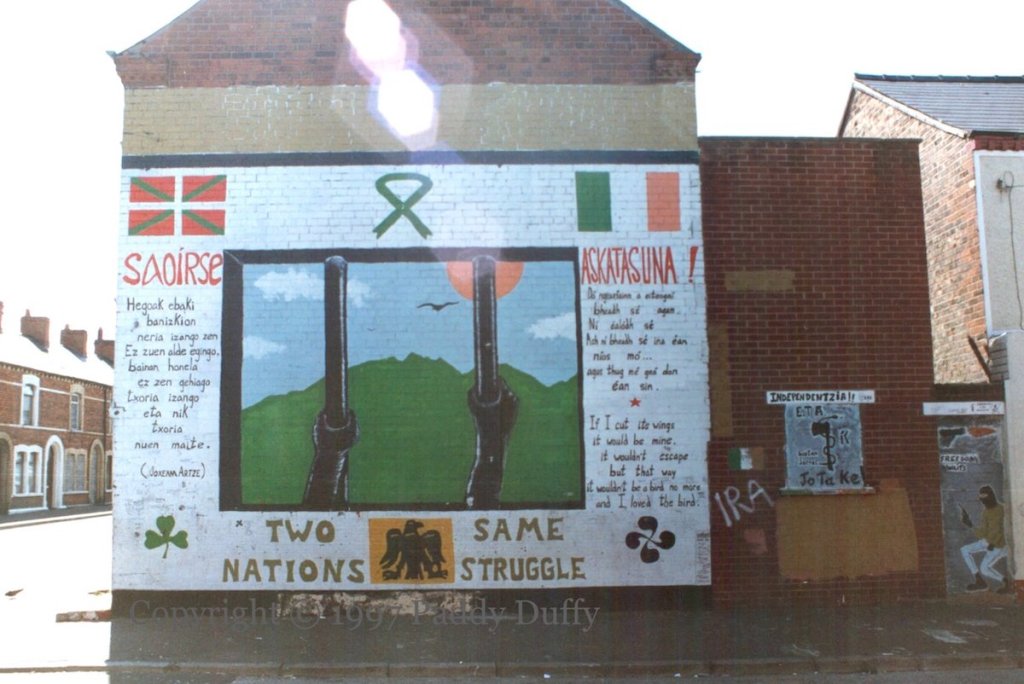

This mural in Clonard contains a green ribbon but concerns both ETA (Basque) and IRA political prisoners. Although the bird is too small to be identified, it represents the prisoner’s longing for freedom. A bird also features in the words: on the left is a poem [without repeating each line, as in the original] by the Basque poet Joxean Artze called “Txoria Txori” (‘The Bird Bird Is’ or ‘The Bird Is A Bird’ in English) which on the right has been translated into Irish and English. The words are not explicitly political, but it’s about not clipping a bird’s wings and it’s written in Basque/Euskara – which are enough to make it political.

“Hegoak ebaki banizkion / neria izango zen, / ez zuen alde egingo.

Bainan, honela / ez zen gehiago txoria izango

Eta nik txoria nuen maite – Joxeam Artze”

“Dá ngearfainn a eiteogaí / bheadh sé agam/ Ní éalódh sé /

Ach / ní bheadh sé ina éan níos mó … /

Agus thug mé grá don éan sin”

“If I cut its wings / it would be mine / it wouldn’t escape /

But that way / it wouldn’t be a bird no more [later changed to “but that ways / be a bird no more”]

And I loved the bird”

A dove above the Sınn Féın offices on the Falls Road, similar to the 1989 Strabane dove.

Here is the sole known exception to the rule: the lark on the right hand side of the Bishop Street, Derry, hunger striker panels. It’s possible that this is post-Agreement rather than mid-90s, but not likely.

The Dove (post-Agreement)

After the Good Friday Agreement (1998) the dove largely disappears. Since the talks did bring peace in the sense of an end to (most) violence and eventually (in 2005) the decommissioning of IRA weapons, the dove had served its purpose and largely disappeared from republican muraling.

One use that it served was in summing up the legacy of the republican struggle and the hunger strikes in particular. Robert Ballagh was commissioned by Sınn Féın to produce a piece for the 20th anniversary of the 1981 hunger strike and came up with the work on which the mural shown below was based, with ten doves escaping an H Block. The work was entitled “legacy” or “The Legacy Of The Hunger Strikes”. It was controversial: “Sands’s family and friends, including Bernadette Sands McKevitt, linked to the Real IRA, said the painting did not reflect the period or represent what he died for. They object to the use of 10 white doves to symbolise the hunger strikers, an image they believe fits in more with current Sinn Fein peace strategy. ‘Bobby was many things but he was not a dove’.” (Guardian)

In 2004, the Bogside Artists thematically concluded their “People’s Gallery” series of murals with one entitled simply “Peace Mural”, featuring a dove and an oak leaf. It is reminiscent of the Bloody Sunday emblem (see above) but is (also?) intended to indicate the end and the goal of the struggle celebrated in the other murals, which portray the Battle of the Bogside, civil rights marches, Bloody Sunday, the suffering of youngsters, and the hunger strikes.

This Bone (north Belfast) mural is interesting in that the use of doves to commemorate the lives of 38 local residents might be influenced by the Catholic influence in the street. The 1798 pike-men are well off to the side, behind the protective cordon of a Celtic cross.

The dove also appeared in murals to plastic-bullet-victim Brian Stewart (2001 X06212) and (carrying a ribbon) in Building An Ireland Of Equals (X05330).

So-called “dissidents” could also use the dove to stand for the peace process that they rejected. Here are “No peace” and “Shove ur dove” graffiti at the junction of Cavehill Rd and North Circular Road.

The dove can also be used in relation to other conflicts, such as the Israel-Palestine dispute:

One strange use of the doves is an Ardoyne Fleadh mural which shows a dove emerging from the hands of Érıu (2002 M01791). The mural might simply mean that peace has come to Ireland, but the combination of mythological Ireland with the dove is unusual.

In this (CNR) Short Strand mural commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Battle Of St Matthew’s, the central image is one familiar from other illustrations of the idea that ‘everyone has their part to play’ but here the dove joins the pencil and the spanner rather than the rifle.

The Memorial Lark (post-Agreement)

Since the Agreement also brought the release of political prisoners, the lark, when it re-emerged, could only represent historical prisoners.

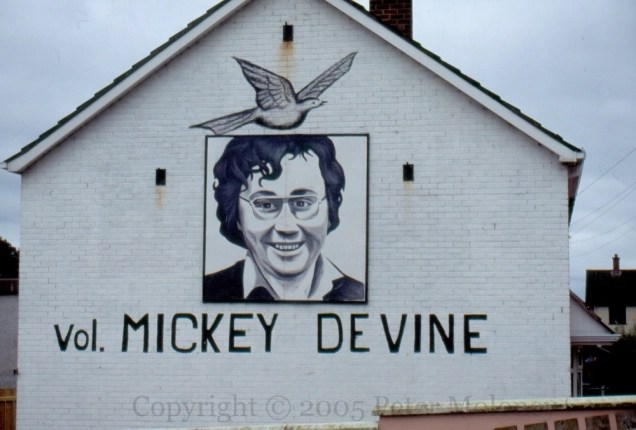

As a pointed example of the switch away from the dove when associated with the hunger strikers (see the Ballagh piece, above), we note that the original Mickey Devine mural (circa 2002) near his sister’s in Rathkeele, Derry, involved a dove …

… but the more recent (2016) mural has no dove and instead a lark and phoenix (2016 X03625). See also the Bobby Sands mural, below.

In this Beechmount mural it is used to commemorate those who died on hunger strike in the 20th century.

This is the bird – presumably a lark – on the hunger strike memorial in the Bogside, Derry.

Short Strand, east Befast.

Stewartstown Road, west Belfast.

Bone, north Belfast

Bogside, Derry

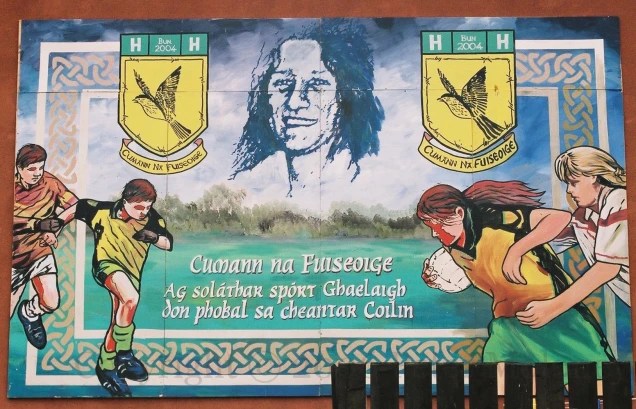

The GAA club in Twinbrook, west Belfast, is named Cumann Na Fuıseoıge (The Larks).

The motif here is reminiscent of Robert Ballagh’s Legacy Of The Hunger Strikes, but the colour probably makes this a lark.

This mural was replaced, in 2011, with a 30th anniversary hunger strike mural that included a lark carrying a ribbon but also what are clearly doves, in the style of Ballagh:

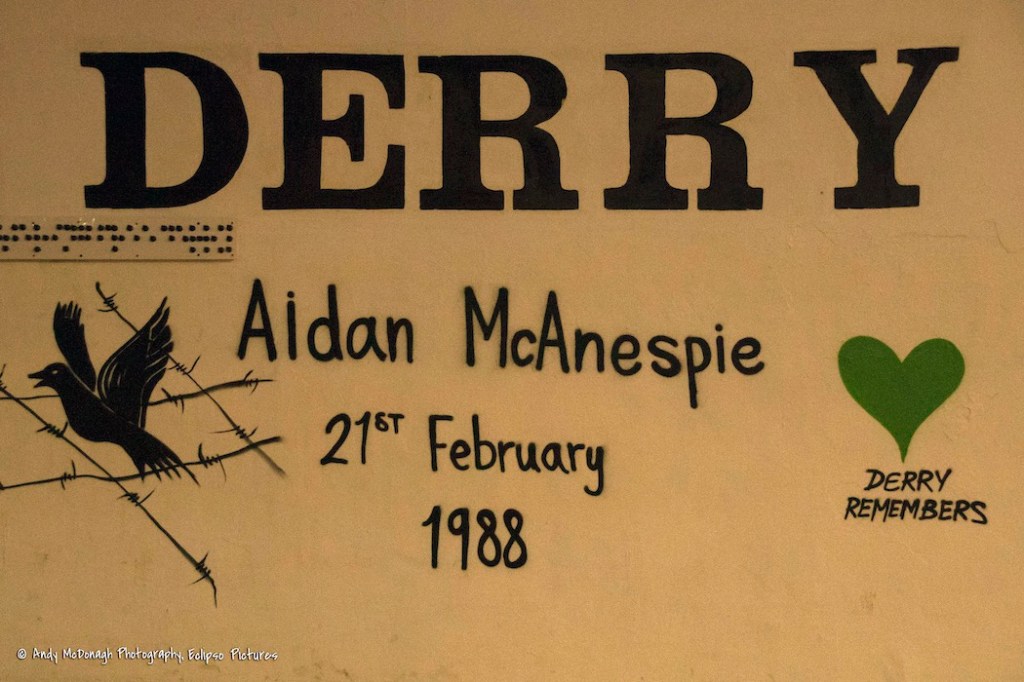

In a 2023 version of Free Derry Corner, a lark in barbed wire was painted in memoriam of Aidan McAnespie and in support of his family at the time of the sentencing of David Holden, the soldier who shot him in 1988. It is used here not as a symbol of the struggle of republicans against the prison system but of the struggle for justice in the UK system.

Non-Use Of The Lark By Anti-Agreement Republicans (post-peace)

The following image is an exception that tests the rule – a lark (a lark of war, no less) in the context of Maghaberry prisoners. But the lark and the Long Kesh tower are included because of a connection between “81” and “02” – the current prisoners are the descendants of those earlier prisoners. The lark and tower are faded in the background while the barbed wire is in solid black.

The Phoenix (post-Agreement)

The phoenix likewise returns to murals after the peace, again to symbolise the historical struggle and in particular deceased IRA volunteers.

See also 2012 X00857 | 2012 X00671 | 2013 repaint of the Clowney Street phoenix X01226 |

2014 X02304 | 2016 X03345 | 2016 X03741

Some post-peace memorial murals have both lark and phoenix, such as the Bobby Sands mural in Sevastopol Street

The phoenix is used by those who wish to continue the armed struggle after the Belfast Agreement (commonly called “dissidents”). The following mural looks much like vintage solidarity murals of previous years, but it is from 2002, on the back of the Bogside Inn (where there is much CIRA and particularly RIRA graffiti).

The phoenix is the symbol of the Republican Network For Unity (RNU):

2017 X04288

2016 X03782

2016 X03603

2016 X03393

2016 X03374

2014 X02029

2013 X01154

Back to the index of Visual History pages.

References in parentheses to mural collections:

M = Peter Moloney Collection – Murals

T = Paddy Duffy Collection

X = Seosamh Mac Coılle Collection

Written material copyright © 2018-2025 Extramural Activity. Images are copyright of their respective photographers.

Back to the index of Visual History pages.