Introduction (Click here or scroll down for Images)

With this eleventh page, we approach the present day and thus cannot be said to be presenting a visual history in what follows.

There are two main threads that we are keeping an eye on, one from the past – re-imaging of loyalist murals – and one that is novel – aerosol art. The emergence of aerosol art explains the selection of 2009 as a cut-off between Visual History 10 and 11

Aerosol art is a rapidly proliferating and rapidly developing phenomenon and treatment of it below is observational and theoretically unruly. We have tenatively divided it into sub-sections on graffiti and graffiti art, on street art, and on street art’s (limited) interaction with murals.

The sub-sections on (on the one hand) graffiti and graffiti art and (on the other) early (i.e. pre-2012) street art set up the historical claim that street art, as it came to develop from 2012 on in Belfast and the north, developed out of graffiti art rather than out of the international street-art movement; and, concomitantly, we note the anodyne nature of street art and its very limited interaction with (political) murals … so far.

(i) Re-Imaging & Re-Re-Imaging

The state-sponsored re-imaging programmes between (roughly) 2006 and 2009 attempted to replace murals depicting loyalist gunmen with artworks on historical and cultural themes from unionism/loyalism and subsequently with community-themed murals and even completely neutral murals. (See Visual History 10 for a list of various themes and the extent to which they might be considered sectional.)

But for the loyalist groups a single engagement with state agencies seems to have been enough and – whether for ideological or pecuniary reasons – hooded gunmen began reappearing on walls from which they had previously been erased, often in historical or commemorative form but a fair number showing volunteers in ‘active’ poses. Thus, this page documents the re-re-imaging of some cultural and community murals with loyalist gunmen.

(As a rule, even if the works do not directly replace a previous mural, we consider state- and civic-sponsored artworks in identifiably CNR or PUL areas to be re-imaging. They are, as one state programme (Communities In Transition) puts it, efforts to get rid of “residual paramilitarism and associated criminality”. We also take pieces produced by community groups who are funded by state agencies to fall into the category of re-imaging artworks. The funding does not have to come directly from a stage agency.)

(Also included in the Images section, below, are some republican murals – or more often stencils and tarps, given their limited resources and support – from “anti-Agreement” (or “dissident” or “militant” or “physical force”) groups.)

The other main thread that is followed in this Visual History page is the development and spread of aerosol art.

(ii) Graffiti Art

The main development in wall-painting generally, would seem to be the rise of graffiti art and especially street art, from 2009 onward. Before we get to street art, let us say something about graffiti (in all its forms: tagging, throw-ups, wild-style writing, graffiti art) though the history of these forms is intertwined with the history of street art.

Tags, throw-ups, wild-style writing, and graffiti art are typically sprayed in abandoned places. Graffitists use pseudonyms because their work is illegal, the illegality being that the walls, although neglected, are still someone’s property.

However, the more ornate forms have steadily gained in popularity and commercial interest, far from their New York home. Legal festivals across the world bring artists together: Drogheda’s ‘Bridge’ jam was started in 1994 (RASK | RASK); the precursor to Meeting Of Styles began in 1997 and moved around to different European cities; Walls On Fire took place in 1998 in Bristol, UK; NuArt began in 2001 in Stavanger, Norway; Asalto began in 2005 in Zaragoza, Spain; UpFest began in 2008 in Bristol. And so on, up to the present day … there were 16 “meetings” of Meeting Of Style in 2022. Festivals and commissioned work have enabled some writers to become professionals and have provided writers with legal walls to spray. Most graffiti artists, however, have remained anonymous and non-professional, and continue to spray in abandoned spaces and run-down urban areas.

In Belfast, there is an underground tagging tradition going back at least to the mid-1980s (DINO, NadX, and others) that went along with the hip-hop scene at the Newsboys Club in York Street (Craig Leckie | Irish Times article about Belfast City Breakers). In 1994, members of TDS (named in homage to the New York crew) went to Drogheda to participate in the Bridge Jam (RASK). In 2008, the Urban Arts Forum (sponsored by Coca-Cola) ran a course in Belfast in aerosol art for youngsters (BelTel). TDS appears to have been the first Belfast crew; other later crews included VN, TCP, RHS, TFE, FA, and TMN. The latter two are still (in the 2020s) operating, as are some unaffiliated writers. (On instagram, you can follow westbelfastgraffiti, belfastscribbles, and belfast_graffiti.)

In 2009, two wild-style writing festivals took place on the most famous wall in Belfast, the west Belfast “peace” line along Cupar Way. This is an abandoned space for locals but a point of interest for tourists. (The history of the art on the Cupar Way “peace” line is described in detail in a separate Visual History page, State Art vs Graffiti On The West Belfast “Peace” Line.)

Writers and graffiti artists have also had to compete for/share abandoned city-centre spaces with street artists. As the next section makes clear, street art in Belfast was first painted on abandoned but highly trafficked spaces in the city centre. Writers and graffiti artists sometimes sprayed on top of these pieces; in the mid- to late-2010s, when the street art festival Hit The North (“HTN”) had become well-established, it gave writers their own walls or hoardings to work on, and a détente was reached.

In the most recent years, Hit The North and the Belfast street art generally has also been painted in living spaces. Graffiti art has not gone with it into these more middle-class and business-oriented areas, and on the contrary there have been rumblings about trying to clean up tagging, as though street art’s increasing respectability were casting a negative light on its older sibling. In October, 2023, a Belfast City Council committee recommended designating legal graffiti spaces as a measure to discourage graffiti (Council Minutes | Belfast Media). A legal wall was launched in mid-2025.

(iii) Street Art

Street art in Belfast appears to come out of writing and graffiti art rather than the political or conceptual art being done by Keith Haring in the USA, Blek Le Rat in France, and Banksy in Bristol. This is evident in the styles of the early artists such as (by 2011) DMC, Verz, and the SPOOM collective (which included KVLR, Redmonk, Friz, and MarcaMix, among others).

In 2012, Culture Night Belfast (CNB) #4 included a public-art component. The 2012 event involved an eclectic mix of writers, graffiti artists, street artists, and art students, spraying on shuttered premises in North Street and the adjacent Garfield Street. Since then, street art has come to predominate greatly, though writers and and graffiti artists are also included, perhaps to keep them on-side in the competition for walls.

The festival has also expanded its locations over the years, and in particular has added locations in living areas, rather than just abandoned and dilapidated space.

In 2013, the event went by the name “Hit The North” (CAP interview) while still being part of CNB. In 2014, it spread to the part of North Street above Royal Avenue, which, like the lower part of the road, was at about 50% occupancy in terms of businesses and so provided plenty of permanently closed shutters. In 2015, a few pieces were painted in North Street but the majority were in Kent Street/Union Street. Like North Street, Kent Street/Union Street was a run-down area, marked for redevelopment as part of a student-housing boom that took a long time to materialise.

However, a few of 2015’s pieces were in other locations entirely. One was Exchange Place/Hill Street, which is a vibrant commercial area completely unlike North Street or Kent Street/Union Street. The effect of this location was to suggest that street art was not just for the empty or abandoned buildings in run-down areas, but had a role to play in a thriving economy. Despite this expansion in location, the name “Hit The North” was retained in this and subsequent years.

The festival took place on the same night as Culture Night – in mid-September – from 2012 to 2018. For 2019, HTN resolved to separate from Culture Night and a small event involving about 20 artists and writers took place in May. Once it was no longer tied to CNB, it could more easily expand into other parts of the city centre that were not central to CNB. The overseas artists generally got the better walls, in parts of the city that were not run-down, or high up in the usual Union Street/Kent Street area, while the locals generally got the construction-hoardings and low-to-the-ground walls.

We might call 2019 and the subsequent years the “Seedhead/Daisy Chain” era to mark the separation from CNB – Seedhead existed prior to 2019 (its first piece was in 2012, by Ed Hicks in east Belfast) but Daisy Chain was established in 2019; both organisations serve as intermediaries between bodies who want to sponsor public art and the street artists who are willing and able to paint it. Where CNB was affected by Covid in 2020 and 2021 and was eventually cancelled in 2022, HTN continued on as before, moving towards more large pieces by big names and overseas artists and continued expansion into other areas of the city centre.

The expansion of HTN and street art generally beyond empty, dilapidated, and abandoned spaces, into “living” spaces is only part of the story of street art’s increasing acceptance. Street art has also come to be employed by businesses and civic/state bodies. The artist of such a piece is to some extent beholden to their paymaster, but the style is distinctively ‘street art’ even when the theme is not. Some might be considered ‘community’ art, though in a different way from the typical community art of the re-imaging period, as described a few paragraphs below. With street art, state and civic bodies can get large-scale paintings that are neutral or weakly sectional in tone. (If the artists were a little more locally constrained in their themes, we would have something like the Mural Arts programme in Philadelphia, USA: large pieces, in local (CNR or PUL) communities, in street art style, depicting community history and people.)

Commercial commissions began in earnest in 2016 and ramped up in the 2020s. Commercial art is like advertising in that its primary function is to tout a business; if the artist achieves any personal expression in its painting, that is a bonus, and if the viewer gets anything else from the piece, that is a bonus.

(The walls or shutters of a business can of be painted with other themes and without any commercial reference; for example, the WWI mural on the shutters of The Peppercorn café did not make any reference to the café and the stoker on the Stokers’ Halt bar is a reference to the heavy industry of east Belfast as well as the name of the bar. We do not count these as commercial art but as sectional, social, or street art, that happens to be on a commercial property.)

Another source of income is the beautifying art commissioned by state and civic bodies for beautification projects, occasionally with a community connection.

Beautifying street art, we suggest, is much more akin to classic, painted, murals than to re-imaging works. Here are some specific similarities:

First, beautifying street art sees a return to paint, rather than the printed boards that have been common since the mid-2000s and were typical of the re-imaging projects.

Second, beautifying street art sees a return to large “gable-end” art that was familiar from classic murals; re-imaging pieces were placed on those same walls, but did not take up the whole wall.

Third, re-imaging pieces often involved images of the people, places, and clubs/associations of the area, and often took the form of collages of old photos; with beautifying street art on the other hand we tend to see graphical symbols representing the area. (And along the same lines, the street-art style is similar to classic murals, in that, although large, they typically have a single motif, and are easily understood.) Beautifying street art often makes some connection to the area but never in political or strongly sectional ways – often the theme is an item of local history or mythology, or a recognisable place or symbol.

Fourth, the pieces sponsored by civic bodies (like those sponsored by businesses) tend to have a longer life than other street art.

We should also note that – unlike the painters of murals – modern street artists are not anonymous or even pseudonymous and indeed need to be self-promoting in order to generate invites to festivals and commissioned works, and to sell merch on sites such as Big Cartel (and, if necessary, enforce copyright). The economic potential of street art was enhanced (in the 2000s) first by the rise of the internet and digital photography and then the rise of mobile technology (the iPhone had been released in 2007) and media-heavy social media (twitter had added the capacity for media in 2010, which is also the year that Instagram was launched). Around the same time, basic websites used for display purposes could be augmented by store-in-a-box add-ons or third-party sellers, and on-line payment systems. All of this means that it’s now possible for talented young artists in Northern Ireland and Ireland to think that with Belfast (or Dublin) as a home it might be possible to cobble together a living based on street art.

The similarities between these large pieces of street art and classic murals might help explain why state and civic bodies are adopting street art, alongside the main explanation of street art’s inoffensiveness.

One enabling condition for the uptake of street art/artists by both businesses and councils is that wall-paintings are considered a common and integral part of expression and communication because of the history of mural-painting and state-sponsored art in Belfast. They are part of the vernacular. They have been produced and/or sponsored by a wide range of bodies for a wide range of purposes: nationalist and republican groups, unionist and loyalist groups, state agencies, community groups, and graffiti artists and street artists themselves, and so it’s not surprising that they are produced by any body that can lay claim to a wall. Here’s writer RASK: “Belfast has always had a mural culture, mainly political, but I think this made it easier to get walls.”

However, the central condition that permits street art this variety of employments (Hit The North, commercially sponsored, civically sponsored) is that most street art is inoffensive, much more so than political murals (with their oppositionalism) or social art (with their entreaties to act better than normal and take care of others), and more broadly engaging than community art (with its localism). Most street art is personal rather than social or political, and so is open to the viewer to find value in the piece; those that do, do and those that don’t, don’t – there’s no question of what a viewer should feel or think, as there is with (political) murals and social artworks.

Similarly, works of street art pieces rarely make reference outside themselves or to larger themes, except to popular culture. A lot of street art is not difficult to interpret, and it does not provoke conceptual reflection. (It is instructive to look at the projects described in the Arts Council NI’s ‘Public Arts Handbook’ from 2005 (i.e. pre-re-imaging) and also at exceptions such as MTO’s Son Of Protagoras (2014 X02245) or Pandora’s Jar in Donegall Street by StarFighterA (2015 X03032) or Sabek’s speared snake (2015, shown below).)

In short, most street art is of a type with the pleasant or affirmative experiences of shared photos and memes on social media: it gets a ‘thumbs up’ … and then the viewer continues scrolling or swiping. If you are the kind of person who ignores or abhors murals (i.e. wall-paintings on the constitutional question), of course, this is not a problem – you take your pistachio of pleasure and move on. (Street art is very skilfully done and one might also appreciate it along those lines if you know something about painting, stencilling, etc.)

The combination of high quantity – our 2024 survey counted 300 pieces of street art, alongside roughly 700 pieces of other types – and short duration – some of it gets tagged, some of it is replaced annually – tends to increase the meaninglessness of street art and encourage an attitude that street art is just one step above graffiti. It might be better if fewer, larger, longer-lasting pieces were produced. Compare Belfast’s street art with Waterford’s or Larne’s or the art from any small-town initiative which does not have to deal with an existing mural or street-art scene.

This gifting of small pleasures upon the viewer has led to street art (as practised in Belfast) gaining acceptance and popularity. Graffiti artists/writers, on the other hand, have remained on the outside. Here’s Glen Molloy, who started out as a graffitist: “The mentality of graffiti art is completely different [from street art]; it’s a rebellious act, an act on society, on injustice, an act of revolt” (Belfast Beyond). Given that writing and graffiti art in Belfast are non-political in their themes, Glen here would seem to mean that the very act of writing (rather than anything about the content of the writing/art) is an act of rebellion, when compared with the fact that most street art in Belfast is painted legally.

Early international street artists, in the tradition of graffitists, had used posters and stencils in order to get their work up quickly and avoid detection and arrest; as time has gone on, street artists have increasingly come to operate legally, with the time to augment the stencilled part of any piece with free-hand spraying, and the use of ladders, scissor lifts, and cranes. (Here is This Means Nothing – later emic – in 2012: “I use paste-ups when working on the streets and use stencils when I have more time (permission) to paint” (Irish Street Art).

Finally, we note a lack of interaction between street art and murals. This is theoretically puzzling, as one can easily imagine street art alongside murals. But despite street art’s advance from abandoned areas into “living” areas, and despite its employment by businesses and civic agencies, in general the locations remain exclusively neutral, non-sectional spaces.

Street art pieces are not identifiable with either sect. As such, street art could perhaps function as an addition or even an alternative to sectional murals. The most direct form of contrast or competition would be to paint street art in the same areas as art identifiable with the CNR or PUL community. But it is (generally) not painted in sectional (CNR or PUL) areas – so far, at least. (The few exceptions are surveyed below.) To repeat a principle from Visual History 10, only sectional (ideological, single-sect) art is produced (by muralists or community artists) in sectional areas.

In theory there’s nothing to prevent street artists themselves from painting in sectional areas, especially if a lesser-trafficked wall were to be quickly stencilled. What a statement that would be, to criticise murals by painting over some republican heroes or some loyalist hooded gunmen!

In practice, however, some kind of local authority is required, and this requires some organising. What we find is when a local group, using its funding from state or civic bodies, commissions a piece, it is usually for a piece of cultural or community art, even when an artist who usually paints street art is hired. And when, on the other hand, street art is sponsored by a state or civic body, it is almost never in a sectional area – that is, instead of using street art for re-imaging, it is used only for what we call “beautification”. The intersection of ‘street art’ and ‘sectional art’ is – so far – largely empty. There has been some increase in the juxtaposing of street art and political art, and street art’s geographical range has been slowly expanding, occasionally into sectional areas – these cases are illustrated below.

We continue to monitor street art’s interaction with murals (i.e. in CNR/PUL communities).

Images

(i) Re-Imaging & Re-Re-Imaging

(i.i) More Re-Imaging

As part of the re-imaging effort of 2010, this cross-community and anti-Troubles piece was painted in PUL east Belfast. A smaller version appeared in CNR east Belfast (i.e. the Short Strand area) – see X01514.

This piece in Lendrick Street was organised by Charter NI and laments the death and destruction that war (WWII and the Troubles) brought to PUL east Belfast.

Re-imaging of the lower Shankill estate continued in 2010 (carrying on from the efforts described in Visual History 10) with another Leslie Cherry board.

The Tyndale Dragon, which replaced some UDA graffiti, was designed by Daniela Balmaverde.

After 18 months on the Shankill Road, Rita Duffy’s Banquet was moved to the Cupar Way “peace” line (where it was soon vandalised by tourists). It had originally been produced via the Shankill Women’s Council with support from the Arts Council for 2011’s International Women’s Day and replaced a QEII 50th jubilee mural. It made way for a Covenant centenary board (X00622).

To much fanfare, the Sandy Row UFF hooded gunman was replaced by a King Billy in 2012.

These flowers (below) look like they could go on any wall, but they are flax flowers and represent the linen industry. They are thus in a PUL area (of east Belfast) on the site of a former RHC mural. They were part of Belfast City Council’s ‘Renewing The Routes’ initiative. (Urban gardens in east Belfast have been painted with street art depicting nature: Connswater | Clandeboye St | Donegall Pass.) It was produced by Deirdre Robb, a long-standing figure in the Belfast visual-arts world; it was replaced in 2018 with a wall painting by a pair of Manchester street artists called Nomad Clan which showed a woman who (it was claimed) was gathering flax – this piece is shown in the final section of images.

A second Lendrick Street piece, below the first, and was part of the 2013 PUL east Belfast re-imaging (overseen by Charter NI, supported by Belfast City Council and the Housing Executive) that added and replaced murals in Templemore Ave (Ulster-Scots M02321 replaced by boxing X01387) and Kenbaan St (UFF M03376 replaced by Tim Collins X01440). Instead of a black-and-white past of UDA men on parade (on the left), the colourful future (on the right) promises peace and diversity.

Community groups often use funds to depict the people from their communities; these pieces are typically historical but omit any mention of the Troubles. This one shows a child “waiting for storytime”, at the Carnegie library on Donegall Road (PUL south Belfast); the building no longer functions as a library, so this is a yesteryear piece. This was one of ten panels depicting local life that replaced ten panels on WWI and WWII.

This is one of two boards together at the Rangers Supporters Club on the Shankill (but probably under the aegis of the Shankill Area Social History (SASH) group); the other is to Shankill women during the World Wars.

(Jumping ahead in time for a moment …) Here is a montage of east Belfast luminaries that goes beyond the familiar pair of George Best and CS Lewis. With funding from the NI Executive.

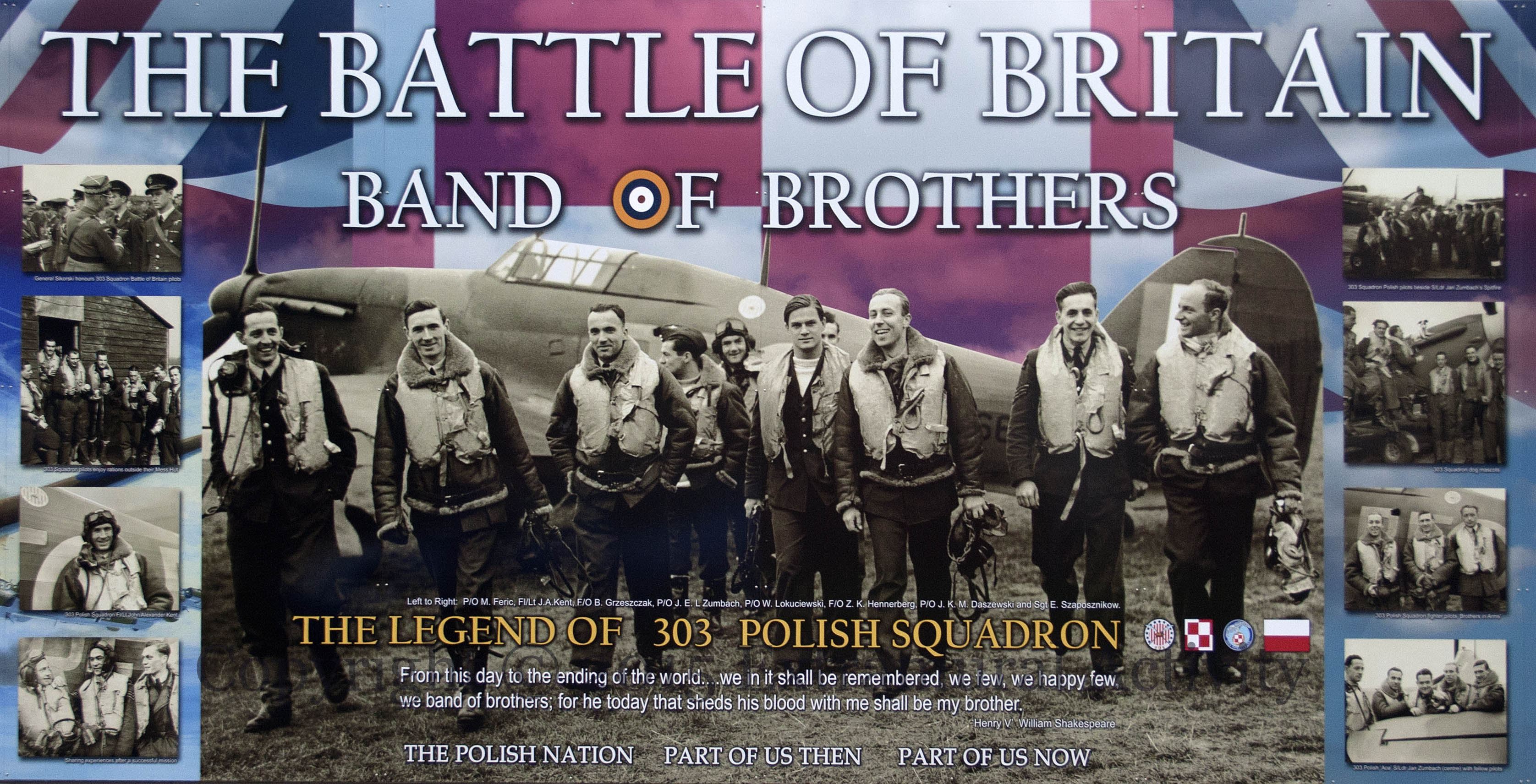

A number of pro-Polish boards were put up in PUL areas. The Legend Of 303 Polish Squadron is about WWII pilots, but its function is to increase the tolerance of Protestant loyalists for immigrant Catholic Poles. For the centenary of the Armistice this piece was decorated with a Polish flag and rosette (2018 X06325). See also Sosabowski (2016 X03418) in the (PUL) Village.

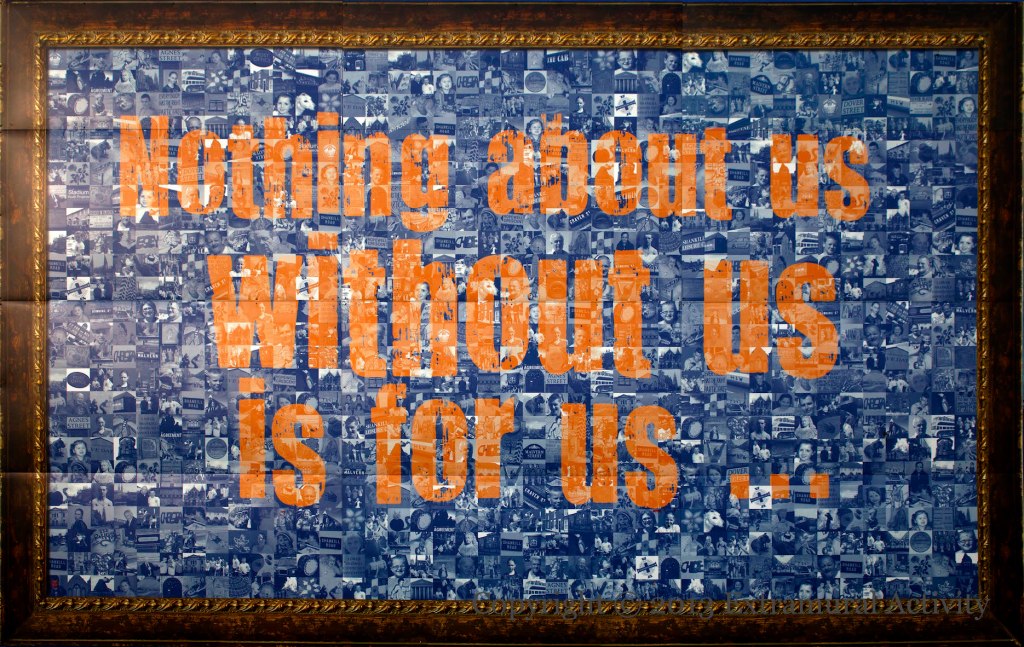

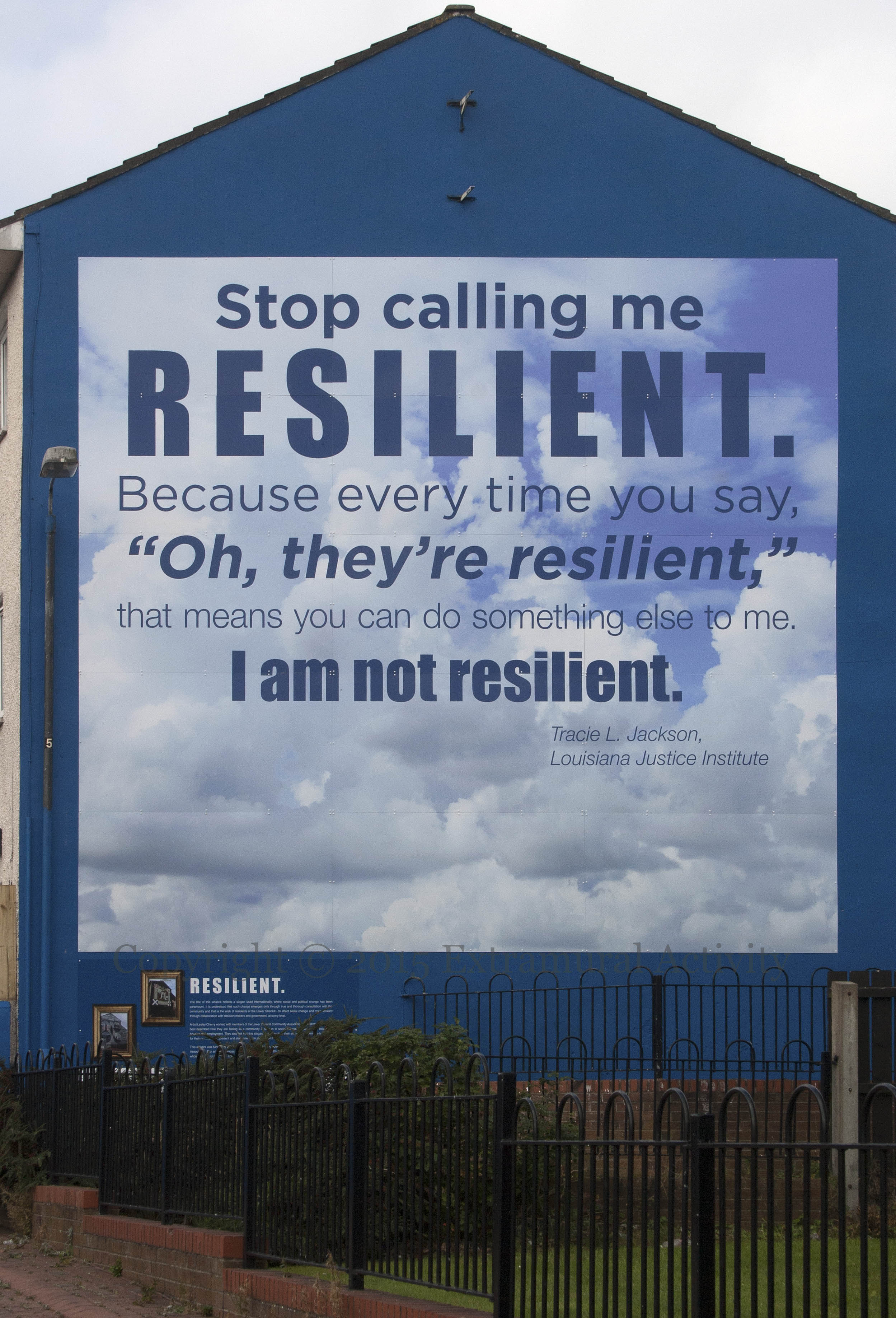

In 2015 three pieces were mounted in the lower Shankill estate. Women’s Voices Matter was added to a blank wall where previously Play had replaced more contentious murals (discussed in Visual History 10), Lower Shankill Angels replaced a loyalist prisoners-of-war mural, and the piece below replaced a Scots-Irish mural (X00285). It was produced by Lesley Cherry and members of the local Association, with support from the Housing Executive. Its intent was to call out the use of the word “resilient” as an excuse to neglect or maltreat neighbourhoods. These 2015 boards were similar in tone and style to Nothing About Us Without Us Is For Us which replaced a cultural mural in 2010.

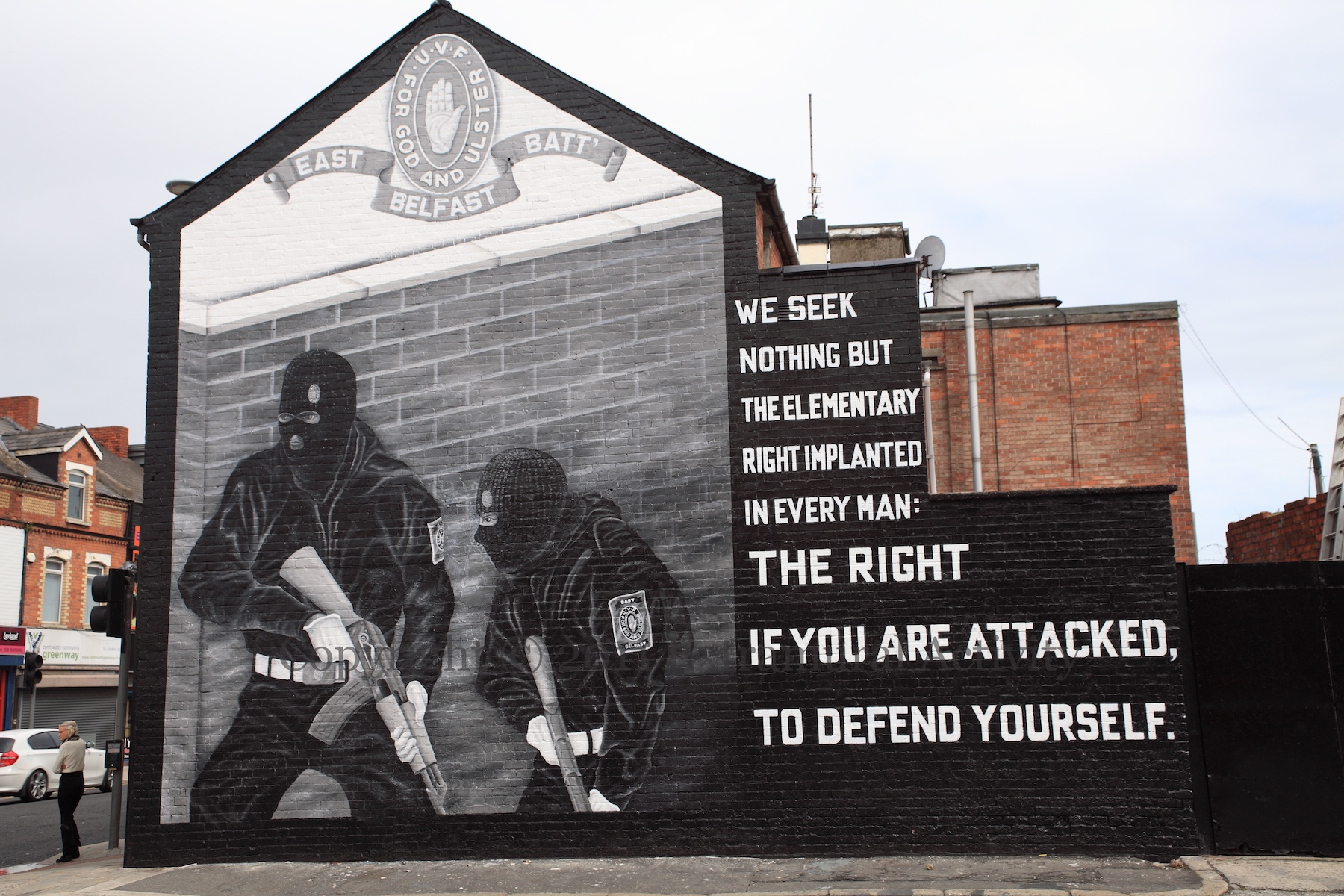

(i.ii) Re-Re-Imaging

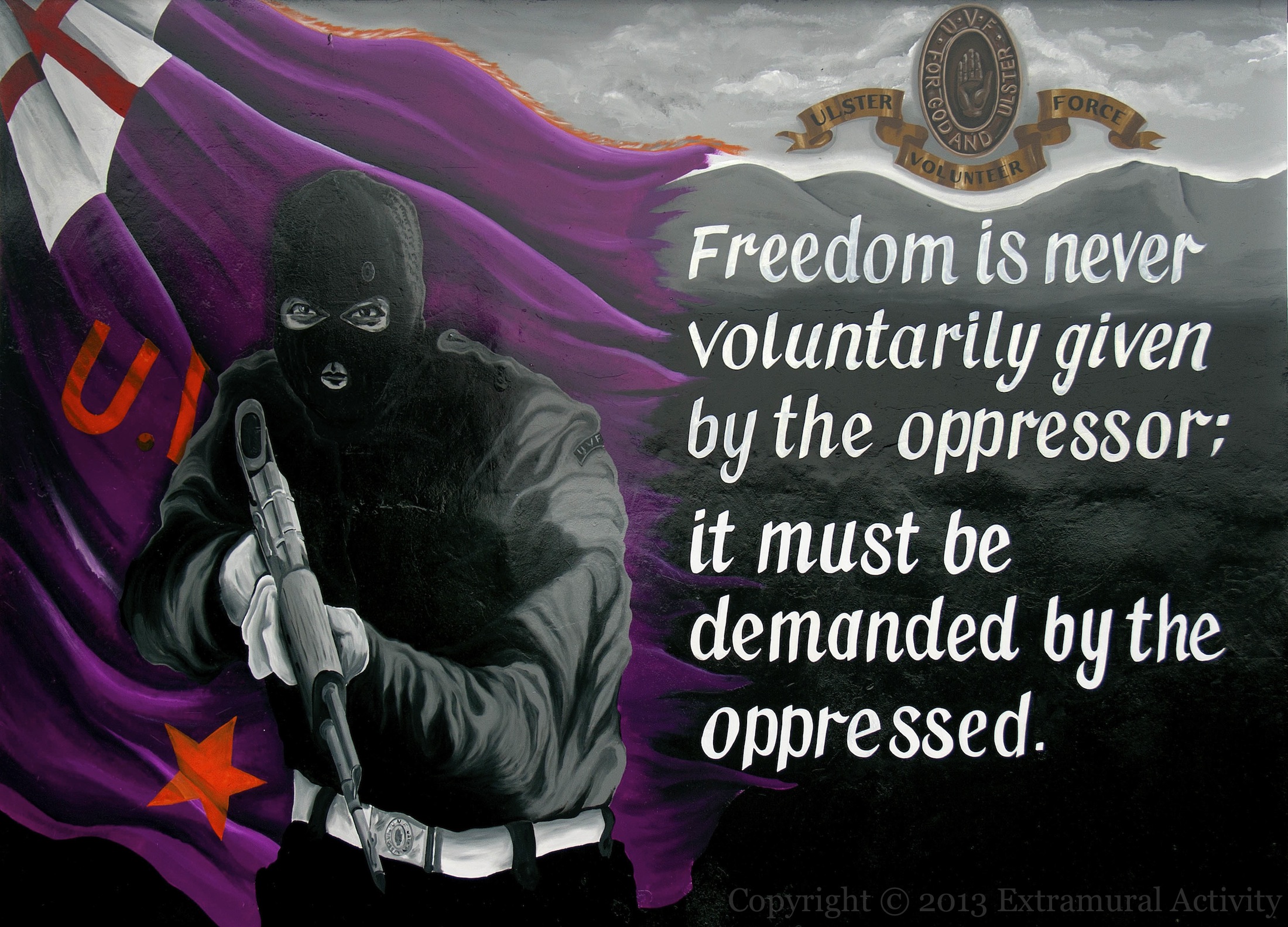

Despite the continued re-imaging of the first half of the 2010s, there were already signs that loyalist re-imaging was implemented only on select walls, while other walls could be painted with paramilitary imagery. A striking example was the hooded UVF gunmen that took the place of a Glentoran Community Trust artwork (that had replaced a Blair Mayne mural and before that a UVF mural). (See the BelTel article “Loyalist murals return to east Belfast“.)

In 2013, in Sydenham, east Belfast, a George Best mural that had replaced a large UVF emblem was painted over and a new mural begun, featuring a hooded gunman with an assault rifle. Work on the mural was halted due to the controversy (BBC | Guardian | U.tv video | Slugger) but ultimately went ahead as planned.

The return to hooded gunmen struck many people as ridiculous. Many parodies of the mural were produced using Photoshop.

Also contributing to the dismissive attitude towards the mural was the misappropriation of Martin Luther King. The quote – “Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed” – comes from the section of King’s Letter From A Birmingham Jail in which he considers the merits of civil disobedience or direct action. He was not, of course, thinking of paramilitarism.

The mural, however, remained in place, and was still in place a decade later as loyalist attitudes hardened in the wake of the Brexit/NI Protocol debacle.

A similar trajectory over the decade from 2013-2024 took place in Carlingford/Ardenvohr streets. In 2013 these Long Kesh gunmen in fatigues were drafted. Locals protested (News Letter) and the mural was changed. In the finished version, the figures on the right were in dress uniforms, and one of them was changed to a graveside mourner. (This was a new mural rather than a re-re-paint.)

But, in 2024, the re-re-imaging of this wall was completed and extended, when the ‘compromise’ mural was replaced by a hooded gunman with assault rifle:

A hooded gunman was also painted at “Freedom Corner” on the Newtownards Road. The gunman dates back to 1991 but it was hoped that he would be replaced when the entire wall was repainted. Those hopes were disappointed: the new, red, version of the mural retained the gunman. Objectors claimed that the gunman would discourage tourists (Tele); this was a dubious claim, given the continued popularity of ‘dark tourism’ (see Visual History 10 and (e.g.) the multi-lingual signage on the corner shop in the lower Shankill in 2015, which appeared even as the lower Shankill was losing so many of its paramilitary murals due to a combination of redevelopment (see Hopewell Razed) and re-imaging – including Stop Calling Me Resilient, above. The gunman was defended as “historical”, though he was not named as any particular historical loyalist or depicted in a way that would assign him to any particular period of the past.

However, the gunman was lampooned for mis-sized hands, his odd expression (had he left the immersion on?), and (especially) for his bendy gun. He became known as “the bendy gunman”. He seemed to have weathered the storm of mockery but once the hubbub died down, both flanks of the mural were repainted, replaced by a list of east Belfast units. Artistic quality is not the point of a mural (see What Is A Mural?) but it appears that in this case – fueled by social media and comparison with street art’s professionalism – its creators thought that the poor quality of the artwork interfered too much with the message.

Other re-re-imaging took symbolic or historical form, rather than hooded gunmen with assault rifles.

Blue Queen in Rockview (seen in Visual History 10) was re-re-imaged by a UDA mural. The image, however, is historical, and also less threatening than hooded gunmen – the volunteers here carry sticks rather than assault rifles and their faces are obscured by sunglasses and scarves rather than balaclavas.

Similarly, a ‘memorial’ UDA mural, using only emblems, re-re-imaged the King Billy (X04465) that had replaced Village Eddie (M02487).

A North Down Defenders mural re-re-imaged the Bingham mural (X01030) that had replaced a paramilitary mural. Its creation was perhaps due to the tension between factions of the UDA in north Down rather than a general resurgence of loyalist gangs.

(i.iii) Other Items Of Interest.

The repainted Kieran Doherty mural in Slemish Way, Andersonstown, drew criticism for its inclusion of hooded gunmen, even in a historical funeral scene. (See the next sub-section for physical-force CNR murals.)

In 2016, the RUA had an ‘art in the city’ project which put (reproductions of) twelve fine-art pieces in frames on downtown walls, including Big Daddy’s Funeral | The Strawman | Rubeys.

This mental health board was supported by the Education Authority; it is surrounded by local threats against drug dealers. CNR west Belfast.

A surprising piece of community-based re-imaging in west Belfast was the replacement of the (aged) Final Salute mural with the word “Believe” among flowers. (The work was funded by a grant from the Housing Executive to the Falls Community Council (Belfast Media) with support from the Resource Centre and USDT.) Up until this point, images of the 1981 hunger strike had been untouchable.

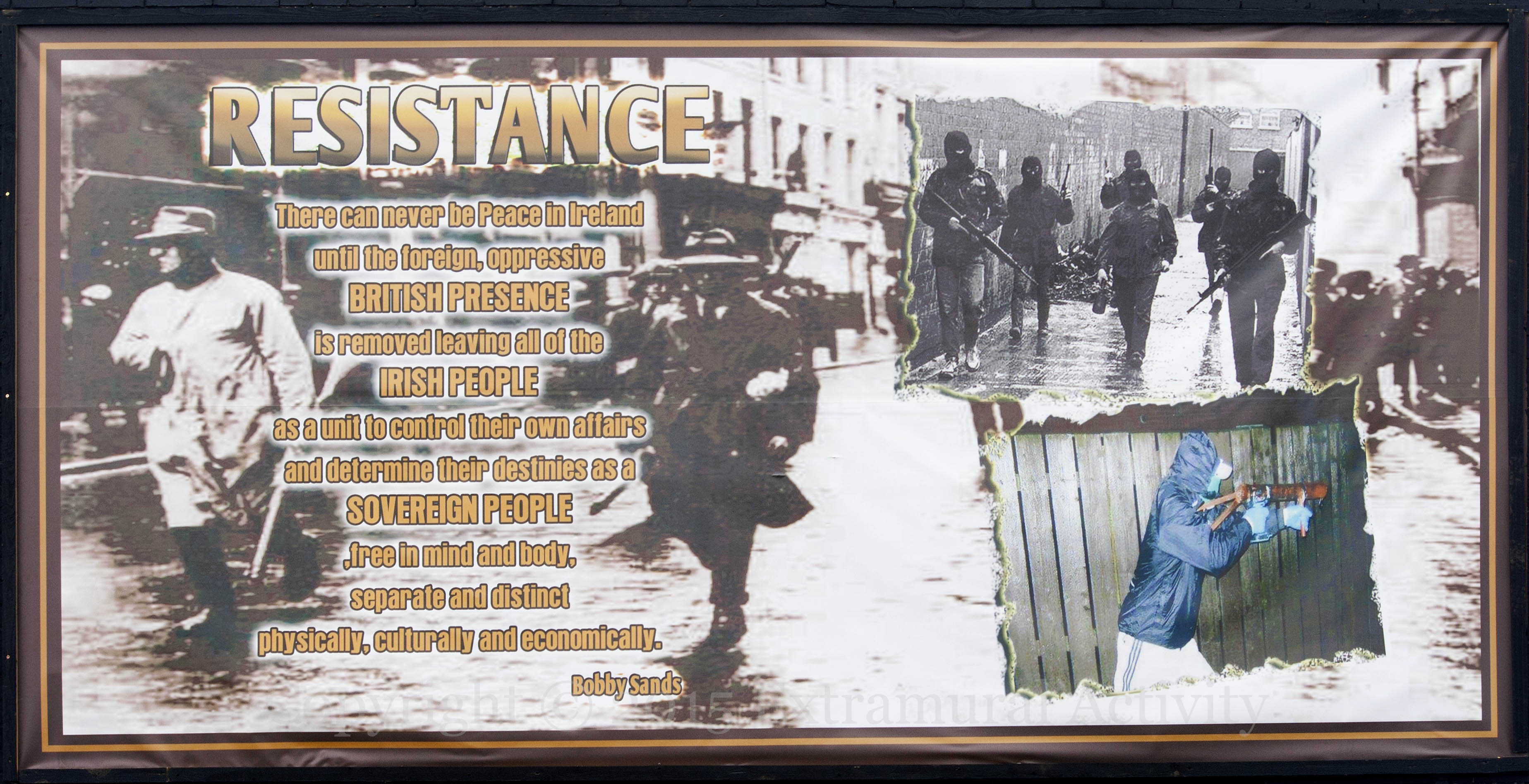

(i.iv) Anti-Agreement Republican Murals

Physical-force republicanism has limited support and its wall art had initially been limited to graffiti and stencils.

However, it was eventually been able to produce larger images on boards and tarps, and in Derry, painted murals. The tarp below was in north Belfast’s Ardoyne neighbourhood. The small image on the right, of a home-made rocket-launcher, was a photograph taken and distributed in November 2014. It caused a stir both because of the type of weapon and also because it was home-made. The photograph or paintings of it would appear in a number of republican murals in Belfast and Derry.

Ardoyne, Belfast:

Creggan, Derry:

This RPG-wielding volunteer is in Derry:

The resurgence of gunmen in murals is good for “dark tourism”, a concept introduced in Visual History 10. A notice like the following, on the tourist hot-spot the “international wall“, however, might not be encouraging.

(ii) Graffiti Art

There have been throw-ups and wild-style in Belfast since the 1980s and such pieces are still being produced. Most graffiti and graffiti art is produced by individuals working unofficially in abandoned and non-sectional spaces but occasionally it has been used for re-imaging or painted in sectional spaces, and it has also been included in the main street art festival in Belfast, “Hit The North”.

An early piece of writing that was both legal and in a sectional area (PUL west Belfast) was the ‘Hidden Treasure’ piece that was used to cover over a piece of UDA boundary-setting in 2004.

(Filth was a member of RHS and TFE and FA – web gallery from 2008 | youtube)

There was graffiti art on the side of Vogue hairdressers in Glen Parade going back to 2008 (usually by TMN’s AKEN, with others from the crew). Although this is a CNR area, the wall is in a somewhat peripheral location (on the edge of Andersonstown) and possibly with the permission, support, and protection of the business. Below is an eagle painted in 2010. The post office staging box has a “political status now” poster on it. In 2018 the graffiti art was painted over in favour of a Saoradh mural.

Wild-style writing festivals took place in April and August 2009 on the Cupar Way “peace” line. These festivals brought writers from around Ireland and the UK to Belfast. In April 2009, Belfast writers and the Shankill ex-prisoners group EPIC organised a festival of 18 wild-style writers and graffiti artists on the Cupar Way “peace” line. This was the most significant recognition of graffiti art in Belfast to that point in time and it came from a sectional community rather than any state agency. (The later festival was included in Bombin’, Beats, And B-Boys. See the separate page on State Art vs Graffiti On The West Belfast “Peace” Line. We have also collected the images from these festivals in a Google Drive folder.)

The graffitists occasionally have something to say. The Sun Will Make You Blind in the city centre was a rare piece of political art from TMN – railing against The Sun newspaper, owned by Rupert Murdoch. In addition to its support of Margaret Thatcher, the paper was also notorious for its coverage of the Hillsborough football disaster – see Total Eclipse Of The Sun and Hold Your Head Up High.

There was some conflict between writers and street artists. The unfortunate record for quickest destruction of a piece of street art by graffitists goes to Dublin street-artist ADW’s contribution to HTN 2015, which was destroyed by NOTA only hours after completion. Where the original piece had said “born to create”, NOTA wrote “born 2 destroy”. By contrast, ADW’s contribution to HTN 2016 has remained completely untouched.

Novice’s HTN15 contribution was also graffitied (X03057) and Glen Molloy’s Two Ronnies in 2017 was also quickly dispatched by members of TMN – see The One Ronnie. (The latter wall, however, was used for a large-scale piece by Colombian street artist Sancho in Hit The North 2018 and remained unscathed.) The alley that had been used by the Vault for a street art festival was taken over for a wild-style jam by the FA crew in 2018-04 (youtube).

Recognising the importance of graffiti art, and perhaps as a gesture of solidarity, quite a few writers – both local and overseas – took part in HTN in 2018. Here is London writer Real1’s piece in Kent Street. On the same street were sprayed pieces by locals ANCO, DOC, VENTS, and StayLo.

In the reduced 2019 HTN (see the next section for a history of HTN), local writer NOTA – referenced above destroying ADW’s art – took part:

And here is long-time Dublin writer PHATS from 2020’s HTN:

(iii) Street Art

We first (iii.i) survey some early street art, which does not appear in sufficient quantities to declare a “movement”, before advancing the claim (in iii.ii) that street art as it came to be practised in Belfast instead emerges from graffiti art. In other words, street art, as it develops in Belfast from c. 2012 onward, looks more like graffiti and graffiti art than the early street art considered in the sub-section immediately below.

(iii.i) Early Street Art

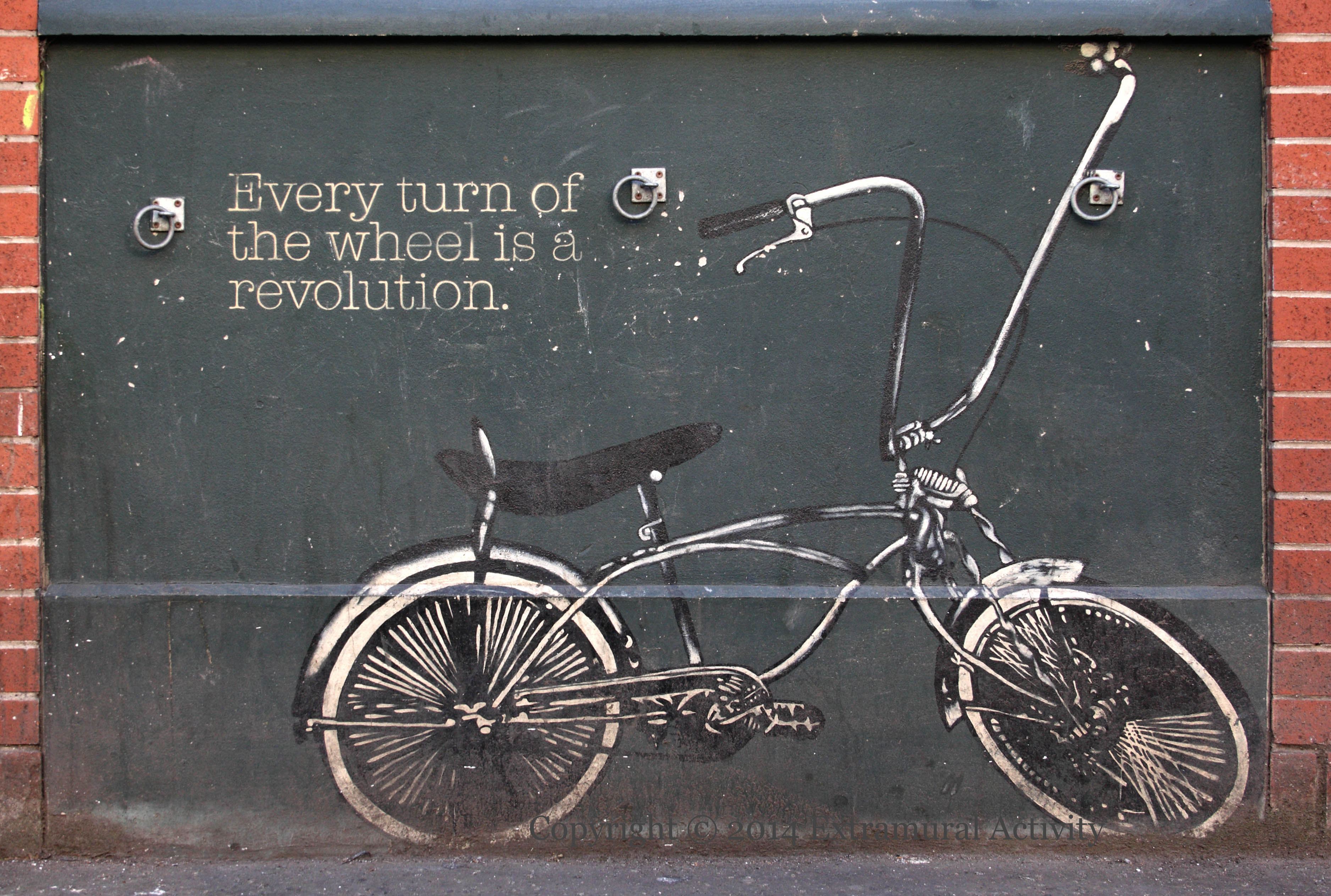

KVLR’s piece on the outside of the John Hewitt bar might be the oldest piece of street art in Belfast. The John Hewitt was set up in 1999 by Belfast Unemployed Resource Centre (BURC | Belfast Media) and named for Hewitt as a “man of the left” who had opened the original BURC on Mayday 1985 (Making Good Money In Belfast | Hewitt Society). The artwork was painted in 2000 (Turkington). Its message is a “global” political one, in support of bicycles and smart urban planning.

In 2004 (or 2003) Liam Gillick’s Quantum Gravity piece was installed in (CNR) lower Ormeau (M04979). According to Gillick’s web site, “His work exposes the dysfunctional aspects of a modernist legacy in terms of abstraction and architecture when framed within a globalized, neo-liberal consensus, and extends into structural rethinking of the exhibition as a form.” But if the Ormeau work does any of that, it’s hard to tell.

In 2005, “Blaze FX – Nozzel” [= Blaze FX and ?Nozzle & Brush?] presented their work as part of the Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival.

In 2006, Banksy’s Sweep It Under The Carpet was used as the basis for a mental-health board on Northumberland St (M05628) and in 2008, two mural artists painted a version of Banksy’s 2005 Bethlehem paste-up, also on Northumberland Street, breaking down a wall to reveal Cave Hill in north Belfast.

These three pieces were painted on an abandoned building where the MAC now is, by Pablo Caamina, writer Filth (web), and Dr Lakra.

In 2009, Verz was one of four artists involved in the re-imaging of the lower Shankill estate, painting two pieces: a community piece about the ’69 Gold Rush (X00298) and a cultural piece about Martin Luther (X00301).

In 2009 or 2010, French stencil-artist Jef Aérosol created three pieces in CNR west Belfast. The one below was on Northumberland Street; the other two can be seen in The Accordion Player.

In Belfast city centre, North St and Garfield Street had for a long time been run down. One reason for this was that North Street Arcade was burnt out in 2004 and sealed up. (See the graffiti from 2004 in Who Burnt Us Out?) To get a sense of the dilapidation in the street, here is the empty building that looms over the North Street car-park:

Writers and artists had already (prior to 2012) been taking advantage of this abandonment. In Garfield Street, on the empty and dilapidated Garfield Bar, Friz painted this “finger choir” in ?2010? (Next to some wild-style.)

At the North Street end of the Arcade, “Condensed Community Confidence” is “out of stock”.

At the other end of the (burnt-out) Arcade, in Donegall Street, Friz and KVLR (of SPOOM) jointly painted a piece for the Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival. This is the version repainted in 2012, again for the Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival:

In comparison both with the pieces presented just above and the street art to come in the history of Hit The North (HTN), here is another piece from the Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival in early 2012, Conor Harrington’s Duel Of Belfast, replacing Maser’s Urban Lover (unurth) on the side of the Black Box theatre. It’s a large piece, in a living area (Hill Street), making a meta-comment on the constitutional question.

(iii.ii) Culture Night x Hit The North

Hit The North began as a public-art component of Culture Night Belfast (CNB) #4 (in 2012), which in that first year was called “Shutter Scape” (youtube) because many of the surfaces painted that evening were on (permanently) shuttered shops along North Street. (The name “Hit The North” (HTN) was adopted in 2013.)

A wide variety of artists took part in Shutter Scape.

Wild-style writers painted over some RECK/JEST/ANCO throw-ups on the long hoarding in the North Street car-park (Andrew Stewart), and on the boarded up entrance to the North Street arcade; TMN’s NOTA painted a shutter.

Here is a Google Street View image of the corner of North Street and Lower Garfield Street, showing, from left to right, the work above by NOTA, Visual Waste’s stencil of an anarchic Zorro with an aerosol can, jokface, DanLeo, ZERT, the remains of a massive ANCO throw-up, RECK, Friz + KVLR, This Means Nothing (later known as “emic”). (For more images, see Andrew Stewart‘s gallery.)

The idea to paint the shutters on North Street was emic’s – then still going by ‘This Means Nothing’ – and he duly painted some shutters. The buildings on the left of his piece (below) resemble (and might be taken from) earlier paste-up work that “represents his views on urban living ranging from the complex and disorderly nature of cities to the social and economic divisions within the metropolis”, augmented here by the figure on the right; the outstretched hand in the bottom left is a trademark symbol – he also painted a stand-alone hand in Garfield Street; the signature is in the bottom right.

On the other side of North Street, an art student going by the moniker ‘Praise’ produced a fine-art (constructivist? suprematist?) piece. We liked it a lot, but perhaps it was too high-falutin’ for the writers: it was soon obliterated by a NIKO throw-up and nothing like it has been attempted since.

Here is a Google Street View image of KVLR’s piece at the junction of North Street and Church Street:

Below the car-park, Friz’s painted the shutters of a working collectibles store. And finally, Verz’s piece declared “North Street Will Rise Again“, even though a recovery would probably mean fewer shutters to paint on.

CNB4/Shutter Scape shows the varied state of aerosol art at the time, as well as the abandoned stare of (most of) the surfaces being painted. It presented a wide variety of non-mural art (i.e. wall-paintings taking a side on the constitutional question): a mix of graffiti forms and street art (and even a piece of conceptual art).

Many of the artists who participated in 2012’s CNB/Shutter Scape continued painting in the years to come. A few of the writers dropped from view, but NOTA, KVLR, Friz, This Means Nothing/emic, Visual Waste, Verz, and DanLeo all persisted. In years to come, a small number of graffiti artists were included but many more street artists were added as the festival expanded.

In what follows, we present a few pieces from each year of Hit The North, particularly from the headline artists who were brought in from abroad. All the while, street art has been experiencing a boom world-wide, including an increase in the number of local artists based in and around Belfast. The claim that street art comes to predominate can be better verified using the map showsing the art produced for the Hit The North festival in Belfast, from 2012 to the present.

In North Street, local artist KVLR painted a skull in an abandoned doorway. This piece is marked “SPOOM” but this is possibly the last reference made to the collective.

A few metres from this doorway, Bristol graffiti legend Inkie was brought in to paint the shutters of a (functioning) tattoo parlour – Lost Soul.

Street artists added to 2013’s festival, now called “Hit The North”, included Hicks from London, who painted a lurid wood (below) in William Street, just off Royal Avenue and away from North Street.

Artists from the island painting for the first time included: Malarky, Redmonk, MELS, Filth, KinMx, DMC, Faigy, David McClelland.

2014 saw MTO come to town, as well as Psychonautes (shown below) who painted on the abandoned Garfield Bar.

The other end of North Street (above Royal Avenue) was used – again, because the buildings were all shuttered. Here is one of two Inkie graffs on those shutters:

Artists from the island painting for the first time included: Marc Mix, JMK.

2015 was irony’s first appearance, along with StarFighterA from Los Angeles. The wall of the old Kent Street car-park was used, prior to demolition. James Earley, from Dublin, painted a giant horse in High Street – by far the most prominent spot for a work of street art so far. Spanish artist Sabek got the following spot, high up on a wall in Union Street and protected by a fence:

Artists from the island painting for the first time included: Le Bas, ADW, Novice.

2016 was almost entirely in Kent St/Union St, but there were a few notable expansions, including SMUG in High Street Court (shown below), and DanK and Sabek in Talbot St.

Artists from the island painting for the first time included: ESTR, Conor McClure.

2017 was the most diffuse HTN, as the main parts of Kent Street and Union Street were not used. Dublin’s Aches (who started life as a writer – see this youtube gallery | instagram) made his first appearance, painting on a wall in the previously unused upper part of Kent Street. Other streets adjacent to the Kent Street/Union Street epicentre were also used.

Artists from the island painting for the first time included: EO’K, FGB, Rob Hilken, Lisa Murphy, Glen Molloy, Caoilfhionn Hanton.

In most years, however, the epicentre of HTN was Kent Street/Union Street. The Sunflower pub – the sole remaining business in the street – served as a watering hole. On the day/weekend of painting, Kent Street would be closed off and tables set up under bunting, allowing spectators to drink as they watched the artists at work on the hoarding erected around the waste-ground. In this picture, from 2019, Leo Boyd’s ice-cream land-rover is in the foreground and the hoarding is receding towards Union Street; the Sunflower can be seen on the right.

(iii.iii) Hit The North Alone

At this point (2018-2019) HTN decided to separate from CNB and put on a jam in May (2019) rather than in the customary September. 2019’s Culture Night (in September) drew between 90,000 (Belfast Live) and 100,000 (BBC) people but – after on-line and scaled-back events in 2020 and 2021 because of Covid – it was cancelled because it had become too “unwieldy” (BBC) – widely understood to include that there was too much drinking!

HTN fared better during Covid and continued on the same trajectories as before, bringing in more overseas artists and expanding into different areas of the city (while still giving space to some writers), with about 30 street artists and 10 writers in 2020.

2021’s event included artists from Japan (Fanakapan) and the USA (Mr Cenz). The Mr Cenz piece was painted at the top of Kent Street next to McKibben’s Court, an abandoned space that is a home for wild-style and throw-ups, and it was eventually swallowed up by wild-style and tagging, like the ACHES piece before it. (See also the Malarko piece covered by RAZER in 2015.)

There were two pieces in the commercial centre of Belfast. There were also three pieces outside the city centre. One was in the university area by English pair Lucas Antics and another was in Ballyhackamore in east Belfast by Decoy. The most penetrating one (that is, into a sectional area) was by emic on the (CNR) lower Ormeau Road in south Belfast (shown below).

2022’s event included a piece by a Belgian artist in Queen Street and another by an English artist in Linenhall Street, and three extra-large pieces, by Asbestos from Dublin, iota from Belgium and KMG from Scotland, high up in North Street/Union Street. The view from North Street (below) shows two of these, by Asbestos (left) and iota (right). (See Belfast Deco for others.) In the foreground, another hoarding (on North Street) can be seen. The TMN tags are on top of TMN graffiti art (Clash Street Kids) that was sprayed on top of tags that had been sprayed on top of street art from HTN 2018.

Among the 2023 artists were Elléna Lourens from South Africa (whose piece was in the university area), Belgian KMG on the (commercial) Dublin Road, another by Dutch pair Studio Giftig behind city hall (shown below), and a large piece in Castle Lane (a shopping district of Belfast city centre) by local artist emic.

The history of Hit The North is still being written. One point worth noting is that when Culture Night returned in 2025, it included a paint-jam, on a hoarding in Garfield Street, on junction boxes in Royal Avenue, and – in a throw-back to the original Shutter Scape festival of 2012 – on shutters in North Street. It appears that street art is now an integral part of Belfast culture, despite the separate existence of Hit The North.

(iii.iv) Early Beautification Initiatives

‘Beautification’ or ‘regeneration’ or ‘revitalisation’ or ‘place-making’ efforts in the urban/commercial centres of various towns have sometimes engaged studio artists to produce pieces, usually on boards, for public display, but they have lately turned to street artists for full-size painted/sprayed pieces. The theme of the piece is often restricted by the sponsoring body, usually by insisting it represents some aspect of the local area.

The potential of art to beautify urban spaces has a precedent in the “Art Student” Initiative of 1977-1981. The programme produced paintings in many sectional areas and so might be considered re-imaging, but since there were no CNR murals until 1981, only the PUL pieces can be considered re-imaging. It’s not clear whether the intent was to beautify run-down areas or reduce militant attitudes or both. The programme was perhaps inspired by similar programmes in Britain, which had plenty of the poverty but lacked the sectarian violence (see Cooper & Sargent’s Painting The Town and – though it mostly covers the 1980s – the For Walls With Tongues project).

Rolston begins his treatment of the programme (1991 chapter 2) by distinguishing it from the ‘community art’ movement of 1960s USA and rightly notes that while the murals in Northern Ireland appeared in local communities, the programme is more properly described as a state initiative (p. 51). (The US community art movement is perhaps more akin to the republican mural movement of 1981. The murals in Belfast and Derry were not undertaken by professional artists and had their impetus in concerns of the community.) He places the programme in the context of the fine art community in Northern Ireland, which was more or less “above” the Troubles. The young artists who went into the communities to paint the pieces were students from the art college on their summer holidays, and they are their superiors might have thought that they were “painting down” by producing art for the masses. The programme began life in 1976 as a pilot project called “Operation Spruce-Up” (Rolston p. 55), the first word suggesting a military/invasion-ary mind-set and the second that the civilian ghettos just needed a little dusting off; two abstract paintings on boards were produced and the following year the students were sent in, though they were required to engage with the community and so were diverted away from abstracts and other incomprehensible forms. The title of Rolston’s chapter on the Art Student paintings is entitled ” “Cooling Out The Community”? “, suggesting that certain areas were perceived as being at a boiling point, perhaps based on sectarian strife as well as material living-conditions. The two were probably combined in the mind of the NI Office: street art would assist these unfortunates in escaping their dire material situation and they would then desist from rioting and taking up arms against the police and army. (See also Watson 1983.)

The programme ran from 1977 to 1981, during which time 43 pieces were painted. Local people and places were painted (“community” themes), but also entirely non-sectional and non-oppositional themes, including scenes from nature, people from pop culture, and nursery rhymes. Only one could be considered political, making an oblique reference to England’s colonisation of Ireland. All (with the one abstract as an exception) were in what we would now recognise as a street-art style. There was another, smaller, initiative in 1987-1988 when a dozen or so pieces were painted, some of which were in a graffiti-art style.

The following artwork – painted in 1979 by Cathal Caldwell & Christine McCormack in the Short Strand, east Belfast – shows the Cave Hill but at such a distance that it is not tied to any particular neighbourhood or even region of the city; being set in the time of bow-and-arrow might suggest Ireland in pre-colonial times, but it probably more strongly conjures ideas of medieval life as portrayed in films and fantasy. The “Smash H Block” and “Bua do na fır pluıd” graffiti to the left indicate that this is a CNR area.

Here is Spiderman in PUL east Belfast, by Leslie Nicholl & Rhonda Brown, painted in 1979, from the collection of Albert McAlpine/Philip McAlpine.

Finally, here is a yester-year street scene (artist unknown) incongruously placed in Divis flats and adjacent to an INLA mural.

Another complicated precedent was the Murals Make Ballynahich Beautiful initiative. In 1997, a group of citizens connected to the studio-art community formed a committee (so, a civically-minded body but not an official government agency or a community group) and over the next handful of years placed at least nine boards depicting local history on the walls of the town. The pieces were loosely connected to the 1798 rebellion, including the figures of Betsy Gray and William Steel Dickson. As such, this collection of pieces might be considered a community-art (or even a re-imaging initiative, given the complexities of the United Irishmen) but the name of the project and the make-up of the group suggests that the fundamental impulse is beautification (BelTel 2000). (See also BelTel 2001.) Shown below is Hilary Bryson’s painting of the Town Council.

A final early attempt at beautification was the six pieces mounted on the “peace” line in Cupar Way in 2009. Many of the pieces were community-themed, as though the wall were being treated as a sectional space; a few were studio art, as though the aim of the project was beautification. The project did not succeed on either score, and over time the true nature of the space became evident, as the concrete canvas proved more suitable for wild-style writers/graffiti artists and for the signatures of tourist who have come to experience Belfast’s top “dark tourism” attraction. (See the separate page on State Art vs Graffiti On The West Belfast “Peace” Line.)

The following image shows a wild-style tag by Derry writer NOYS next to studio artist Kevin Killen‘s red face; between them is a sign reading “Please respect artwork” – the tag is covered in signatures and the metalwork was later stolen for scrap but dumped by the side of the road. In 2025 it was placed in a new coffee shop at the top (Lanark Way end) of Cupar Way – see I’ve Been All Around This World.

We will return to beautification programmes after a brief consideration of commercially-sponsored street art, which takes off in earnest c. 2013.

(iii.v) Businesses & Street Art

It took a while for businesses to embrace wall-paintings and to find street artists.

A early and self-referential form of commercial art was art for “dark” tourism (see Visual History 10) that featured art from or about the pre-Agreement period. Below is a mural pitching tours in a (CNR) black taxi. Another, more controversial, mural is the Coıste tours mural in X00432.)

Art has been used to cover over abandoned shop-fronts. These are on the Newtownards Road, but the tactic was used in various towns across Northern Ireland: more Newtownards Road | more Newtownards Rd | Gresham St | Glengormley (Newtownabbey) | Bawnmore (Newtownabbey) | Ballyclare | Portaferry | Dungiven | Armoy | Springfield Road, Belfast (houses rather than shops).

A south Belfast property-manager commissioned a wall-painting of golfer Rory McIlroy in 2012 (so, commercially-sponsored but not commercial in theme), but he hired CNR muralists to do the painting. The same artists also painted Madden’s and McMahon’s pubs. CNR artists also painted the Whiterock branch of Sean Graham’s (bookies), six shutters for O’Connor’s Bakery, the entryway into the Dark Horse (bar), Benny’s (café), Manny’s city centre & Manny’s north Belfast (fish-and-chip shops).

The following is an incomplete list of commercial art painted by street artists:

Inked (2013) | Atomic Collectables (2013) | Lost Soul tattoo (2013) | Blackjack Tattoo (2015) | Belfast Underground (records) | Glass Slipper (ballet and dancing shoes) | Thompson Crooks Solicitors | McLean’s Bookies | Heverlee | Dirty Onion | White’s Tavern | Kelly’s Cellars | Harp Bar | Cigar World | Kids Store | Urban Ink | Muddlers Club (bar) | Short Bark & Sides | The Art Department (club) | Dance Addiction | Patisserie Valerie | Hickson’s Point (bar) | Old Time Favourites (sweets) | Lower Ormeau Café (see below) | Joker Tattoo | Harp Bar (youtube) | Guilt Trip (coffee) | ProKick | Tribal Burger interior | Ciggy Vapes | Bradbury Art Store | The Juice Bar | White Dragon (bar) | E Kou Xian (Seafood) | Praxis Care | Deerah (restaurant) | Jeggy Nettle (bar) | Fish City | Bellevue Zoo | Vineyard (off license) | La Taqueria | Bunelos (donuts) | The Gym – wild-style | Common Market | Eatwell Health Foods.

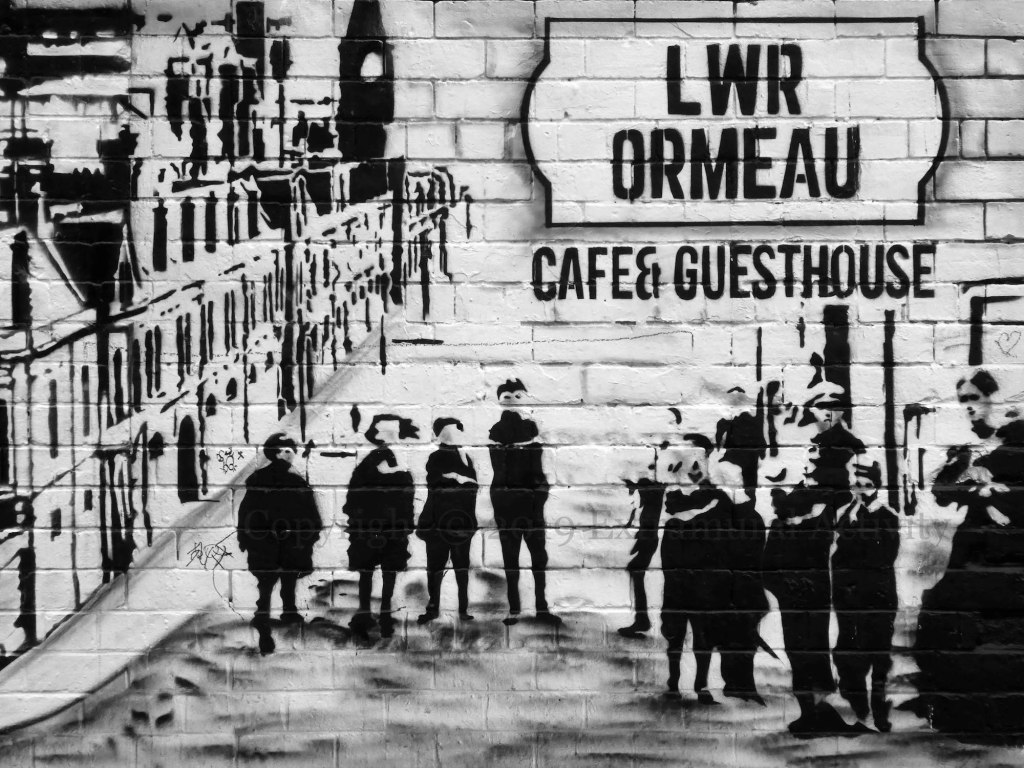

This Lower Ormeau Cafe & Guesthouse artwork is clearly branded but shows the nearby Belfast Gasworks in Victorian times, giving it a community-art feel. Artist unknown.

(iii.vi) Later Beautification Initiatives

Street art increasingly became the choice of government agencies and community groups in the late 2010s. We present here some of the larger programmes.

2018 In March, Nomad Clan (shown in the final section, far below) and Friz painted pieces as part of Belfast Weekender. The Nomad Clan piece was on the main Newtownards Road, opposite Freedom Corner, and so counts as a street art intervention; as mentioned above, it was on wall that long ago bore a RHC mural. Friz’s piece was related to C.S. Lewis’s Narnia fables, and was painted at the new C.S. Lewis square, which is also where Wardrobe Jam took place in June; the assembled street artists painted mostly wardrobes and electrical boxes (see Andrew Stewart’s gallery) but Danni Simpson painted these Aslan heads on a wall.

The ‘Belfast Canvas’ project aimed to decorate electricity and other utility boxes. For the first few years (2019-2022), these were in the city centre. In 2023, a few were painted along the Antrim Road, including in the CNR New Lodge and middle-class stretch of the arterial route. Here are street artist Rob Hilken’s take on north Antrim foods dulse (the seaweed in the foreground) and yellowman (the yellow honeycomb in the background) in the city centre, and a tiger/cat-with-attitude by graffiti artist PENS on the Antrim Road. (The Belfast Canvas Project has its own Visual History page, which also includes the boxes painted by a mural artist in CNR west Belfast.)

Ballynahinch’s choice of the 1798 rebellion and the United Irishmen found an echo in the Belfast Entries project of 2020 onward. This initiative employed street artists to produce pieces related to Belfast in the 18th and 19th centuries in the entries of the old centre of Belfast city. For many, this meant artworks on the United Irishmen, a political group from the 1790s pledged to Irish independence, but less threatening to modern viewers because “cross-community” in its membership and aims. The Irishmen were generally associated with “progressive” causes of the day, such as the amelioration of poverty, maternal care for women (see X11550), and the abolition of slavery, as in this piece (by London artist Dreph in Joy’s Entry) of Olaudah Equiano, who visited Belfast in the winter of 1791-1792 and stayed with United Irishman Samuel Neilson.

(The Belfast Entries Project has its own Visual History page.)

In Dundela, east Belfast, at the Belmont Road shops, Glen Molloy painted three pieces in the summer of 2021, the first of local kickboxing gym ProKick, the second of Maya Angelou, and the third of Samuel Beckett. (Emic also painted a piece on the side of The Strand cinema.) The Angelou painting was vandalised with racist slogans and the Beckett piece was vandalised with whitewash when it was painted a few weeks later. It’s not clear from which direction the vandals had come. The artwork was (mostly) repaired and the following year a tribute to Ukraine was added on the far left. The whole thing was replaced by a Joe Strummer painting, also with an uplifting message, in 2023.

The beautification of the Holylands area of south Belfast began in 2015 when a run-down alleyway was turned in a ‘wildflower alley’ by the College Park Avenue Residents Association. Additional regeneration projects involved Forward South and the Belfast Holyland Regeneration Association. A number of artworks were painted in the area: Funny Things Are Everywhere by Lucas Antics in 2021 as part of HTN2021 | Wildflowers by emic in 2022 | A Mother’s Love by Elléna Lourens as part of HTN2023 | Mount Charles flowers in 2023. Take These Seeds was painted by emic in 2022 and its theme did double duty: it shows a sunflower, which fit the local efforts to revitalise alleys with flowers, but also made a connection to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Finally (in the Holylands), a large piece of street art, called Horsey Hill (shown below) was painted in 2023 by community artist Daniela Balmaverde with street artist DMC. Compare this with earlier pieces of community art by Daniela, such as her 2009 re-imaging piece in Glenbryn (PUL north Belfast).

Cavehill Road runs through a middle-class area of in north Belfast. A consortium of businesses along the road, rather than a governmental body, sponsored three pieces, but the theme was local wildlife and not the businesses themselves. Three pieces – Swan | Fox (shown below) | Squirrel – were painted in late 2023 by street artists Danni Simpson and Mr Fenz, with a fourth one added in 2024 – Under Ben Madigan.

Here is a list of beautification initiatives. Unless otherwise noted, the artists involved are street artists.

- Belfast: all areas (1977-1981) ‘Student Art’ initiative – see above

- Ballynahinch (1997-2000) studio artists – see above

- Belfast: Cupar Way “peace” line (2009) studio artists – see above

- Belfast: City Centre (2019-2022) “Belfast Canvas” – see above

- Downpatrick (2019) – Friz | five others by DMC | JMK | KVLR | emic | DanLeo | Friz

- Larne (2019) – ‘Game Of Thrones’-inspired art on boards by studio artists Geraldine Connon | Dawn Aston | Audrey Kyle | Kim Montgomery (Mid & East Antrim Borough Council with Larne Renovation Generation and the Traders Forum)

- Bangor (2020) – studio artist Sharon Regan | studio artist Terry Bradley

2021

- Ballycastle – aches | Friz | JMK | Shane O’Driscoll | Laura Nelson | emic | Rob Hilken | irony

- Bangor – Carla Hodgson | Friz | irony | DanLeo | KVLR (?) | also a commercial piece by Holly Pereira

- Belfast: Ballyhackamore – DECOY | Alana McDowell | emic | Hicks (Eastside Partnership and Ballyhackamore Business Association)

- Belfast: Dundela – Steven Hackett & Glen Molloy | Glen Molloy | Glen Molloy (which later became an emic) | emic + Rob Hilken (2024)

- Belfast: City Centre “Belfast Entries“

- Newtownards – street art jam in Meeting House Lane involving Annatomix | Friz | NRMN, RAZER & NOYS | Rob Hilken | FGB | KVLR | Irony | ?kairos? | Carla Hodgson | Danni Simpson | Not Pop | Zippy | Mr Fenz | Kerri Hanna | emic | Laura Nelson | Alana McDowell

- Belfast: Holylands (2021-2023) – Lucas Antics | emic | emic | Daniela Balmaverde (see above)

- Enniskillen – Mr Fenz & Danni Simpson | Mr Fenz & Jordan Shaw | Friz

- Ballymoney – Irony | Shane O’Driscoll (Causeway Coast & Glens Council)

- Coleraine – emic | Rob Hilken (Causeway Coast & Glens Council)

- Limavady – Rob Hilken | Claire Prouvost | irony | Not Pop | Alana McDowell | FGB | KVLR (Causeway Coast & Glens Council)

- Portstewart – DanLeo, KVLR (Causeway Coast & Glens Council)

- Portrush – aches, FGB, KVLR x 2 (Causeway Coast & Glens Council)

- Larne (2021-2022) – emic | Visual Waste | emic | iota | two pieces painted by PUL artist Dee Craig | Alana McDowell | also a commercial piece painted by Mr Fenz

2022

- Banbridge – Rob Hilken | FGB | Friz | Decoy | Holly Pereira (Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council)

- Bangor – emic

- Coleraine – Michelle McGarvey & Amy O’Brien & Sarah Carrington

- Enniskillen – Kevin McHugh | Kevin McHugh | Kevin McHugh | Kevin McHugh | Friz | unknown | Danni Simpson & Mr Fenz (2023) (Enniskillen BID and Experience Enniskillen)

- Downpatrick – Friz & NRMN | ?RAZER? | emic | NOYS | ?RAZER? | Wee Nuls | unknown | Verz | Zippy | Friz | Kieron Black | unknown

2023

- Lisburn – Visual Waste painted six panels from/based on the children’s book Guess How Much I Love You.

- Bangor – Friz | Carla Hodgson | street art jam in early 2023 Codo, Jimbo Slice, FGB, HM Constance | street art jam in mid 2023 Aoife Laverty, Chop Suey, Ana Fish, HM Constance | also a commercial piece by Visual Waste (it is not clear that later jams are sponsored by civic organisations)

- Carrickfergus – DanK | emic | Glen Molloy (Northern Ireland Alternatives, International Fund for Ireland’s Peace Impact Programme)

- Antrim & Newtownabbey borough council’s Botanical Borough initiative, seven small flowers and four larger pieces:

- Randalstown – flax by Hixxy

- Antrim – bluebells by Hixxy; Andy Council

- Crumlin – wild rose by Hixxy; Woskerski

- Ballyclare – flax by Hixxy; Holly Pereira

- Whiteabbey – cherry blossom by Hixxy

- Monkstown – flax by Hixxy; Rob Hilken

- Glengormley – forget-me-not by Hixxy; Kitsune

- Belfast: Lisburn Rd – emic | Zippy

- Coleraine – ‘ReVITALise’ project: Friz | Shane Sutton | emic | Rob Hilken | Karl Porter | Friz | Meadow Toye | small pieces/electrical boxes by Coleraine Youth Collective | Sarah MacKay | Claire McDowell | Sara Carrington | Marc Holmes | Lisa Anderson | Maria McLarnon

- Belfast: Linen Quarter – Linenopolis by Visual Waste | tribute to Terri Hooley by RAZER & NOYS, Rob Hilken, Alana McDowell, Not Pop, Zippy | Birds by Annatomix (Belfast City Council and Linen Quarter’s ‘Great Expectations’ initiative)

- Belfast: Cavehill Road – Fowl Play (Swan) | Outfoxed (see above) | Squirrelled Away by Danni Simpson and Mr Fenz

2024 …

- Belfast: Garfield St (May)

- Bangor: one | two (July)

- Larne: “Hit The Coast” (August)

- Derry: “Get Up, Derry” (August)

- Belfast: York Street Station “Tunnel Vision” (August)

- Newcastle: Cha Cha | FGB | HMC | Katriona | Kerrie Hanna | KVLR | Leo Boyd | Lost Lines | MWAK | SzuSzu (September)

(iii.vii) Political & Social Works By Street Artists

As the list of recent state-sponsored pieces shows (especially when cross-referenced with locations on the Map), street art and the street-art style in state- and civic- art has (so far?) been confined to town centres. And emerging from all of the foregoing is the idea that – as a general rule – street artists paint aesthetically pleasing or community or nostalgic art in neutral spaces (both empty and living). Neither has commercially-sponsored art appreciably expanded street art into sectional areas.

In addition to the street art and commercial art, (street) artists do occasionally tackle political and social issues. We present a number of such images below, but it should be remembered that the overwhelming majority of street art is not political or social. What follows are socially- and politically-themed art in the city centre and neutral spaces; social/political art in sectional areas is presented in the next section.

The RHI (Renewable Heat Incentive) scandal drew some comment from aerosol artists. This piece showed Arlene Foster as a dragon-formed dealer; another gave the a recipe for Foster & Bell’s Flaming Hot Tottie.

Ciaran Gallagher (web) is a studio artist who has also produced dozens of pieces for the courtyard of the Dark Horse in Belfast’s city centre, many of which provide satirical commentary on the follies of political life in Northern Ireland and Britain. Here (below) is his comment on “Namagate” in 2015. The message here is perhaps a general “anti-politician” or “anti-corruption” one, rather than being aimed at any specific political party. See also his chronicling of the Conservative leadership turmoil (Boris Johnson – Liz Truss – Rishi Sunak) in 2022: And In The Blue Corner … (Truss vs. Sunak) | It’s A Knockout! (Truss wins) | Broken Promises (Truss crisis) | Ship Of Fools (additional election). Originally these were in Hill Street, but they are now in the Dark Horse courtyard.

Republican graffiti in west Belfast (in support of the people of Donetsk) was obliterated (perhaps after even earlier damage) by a giant MASH tag. The throw-up itself is not political, but we take the act to be political.

There were also several pieces in support of the Ukrainian people, one in the city centre by FGB (Ukraine Has Suffered Enough) and another by emic in (non-sectional) south Belfast (Take These Seeds). In east Belfast, a Ukrainian flag was added to the Maya Angelou piece that had been vandalised in July 2021 (X10737 2022).

Leo Boyd produced a ‘No war’ poster, showing a Russian bomb turning the planet into a graveyard.

The only commentary on the sectional divide in Northern Ireland has come from TLO (Three Letter Organisation) who has directly criticised loyalism. These were bold and sometimes shocking pieces and were confined to the city centre (rather than placed in PUL areas). After receiving criticism from within his own (PUL) community, TLO stopped producing posters in 2019 (source: personal conversation).

Here is TLO’s take on the use of tyres in pyres, which is not allowed for bonfires receiving funds from the Bonfire Management Programme. Eighteen other TLO pieces are discussed in the Seosamh Mac Coılle collection but for the unfiltered experience, see Ornamental Hermit.

A piece was painted to Lyra McKee, a young journalist shot and killed by a member of the New IRA while observing a riot in Derry. The artwork was painted in (Belfast) city centre but note that it taps into the ‘It gets better’ campaign and gay rights rather than/as well as the violent dimension to her killing – the quotation is from a letter McKee wrote in later life to her 14 year-old self.

Wee Nuls’s piece advocating for free period items was originally painted in March 2021 beside Transport House but painted out almost immediately. This new version, with redacted chest and crotch, was at Artcetera in Rosemary Street.

In Derry, two pieces were painted by street artists in late 2019 to coincide with an “Art And The Great Hunger” exhibition. This one was by Shane O’Malley; the other was by OMIN (X08448).

The Covid lockdown of 2020-2021 brought out a satirical graffitist in east Belfast who went by the name of Hallion and wrote on walls suspiciously close to the Vault. In Tower Street: Wash Your Hawnds and Wash Yer Hands. To the east of Westbourne St: In This Together | Except For Cummings | Wear A Mask. On the corner of Westbourne St: Wear A Mask Or The Easter Bunny Gets It | Thran Rights Nai (shown below) | Where’s Our 600 Quid?

Unlock Your Lockdown by street artists Laura Nelson and Leo Boyd for Women’s Aid NI.

(iii.viii) Outside Entities

Even outsiders (typically NGOs and charitable groups) also know that the thing to do in Belfast is to sponsor a wall-painting. Here are a two examples from non-local charities:

This “Manchester United Big Lily” was painted by CNR muralists on CNR Northumberland Street:

This large wall painting was produced by Visual Waste for International Women’s Day 2022, with sponsorship from Children In Crossfire.

(iii.ix) Street Art In Sectional Areas

In the images that follow, we (finally?!) turn to instances of street art or graffiti art in sectional (identifiably CNR or PUL) areas. We begin with examples of street artists hired to paint sectional (CNR or PUL) pieces, and then to street artists painting social messages, and then turn to cases that – it might be argued – are works of street art (without any qualification) that might be a direct competitor to murals.

Sectional (CNR/PUL) Art Painted By Street Artists

(In other words: sometimes street artists are hired to paint pieces with sectional themes and in styles that pass for mural style.)

In June, 2011, Glasgow street artist SMUG reproduced a photograph of the funeral cortège of Richard Mussen on the Shankill (X00490).

In 2013 and 2014, street artist JMK painted two murals in Tiger’s Bay, on the WWII blitz (2013) and on different auxiliary roles taken during WWI (2014). (In 1995, JMK was a member of Farset Artists, which painted a Great Hunger mural in the New Lodge.)

In 2020, street artist Glen Molloy painted The Relief Of Derry in Tullyally, Londonderry (X07156).

This next image is a UDA mural from the repainted “Freedom Corner” in east Belfast, painted by Blaze FX, a pair of artists who specialise in ‘schools and community’ artworks.

Other Blaze FX pieces for the UDA include the Stormont mural in Kilburn Street (2012 X00850), the Tommy Herron mural in Bangor (2019 X06858), and the ‘sunglasses’ mural in Avoniel Road (2021 X09779). See also the ‘Proud, Defiant Welcoming’ version of Welcome To The Shankill Road (X06703 dating to 2009).

In 2023, Glen Molloy painted ‘cultural’ pieces on the Shankill and in Carrickfergus.

All of the works listed above are in PUL areas.

In Derry, all-purpose graff-writer/street-artist RAZER has painted some CNR murals, most notably a pro-Palestinian image on Free Derry Corner in 2023.

In 2024, in the (CNR) New Lodge, Belfast, emic painted a female figure in dark clothing holding a rose. This might have been interpreted neutrally, along with the other (brighter) flower imagery painted on the low walls – see Communities In Transition and New Lodge Gardens. However, the figure will be easily understood by nationalists to represent Róısín Dubh/Dark Rosaleen, who stands for Ireland and its mistreatment. This very skilful piece walks a very fine line very precisely: the lack of explicitly nationalist or republican signifiers is perhaps necessary if the piece is to be funded by Communities In Transition, while the cultural reference is perhaps necessary if the art is to survive on what had for the past dozen years been an anti-Agreement wall – see Damn Your Concessions, England and Unbowed, Unbroken. Compare this piece to another emic piece, in Creggan, Derry, which did not have any ready CNR interpretation and was marked with republican graffiti within a year of painting – see Stand Up And Speak Out.

Socially-Themed Art Painted By Street Artists

(In other words, street artists are sometimes hired to paint pieces with social messages.)

emic painted a suicide-prevention piece in CNR west Belfast (2016 X03671)

Visual Waste painted this mental-health piece in CNR west Belfast in 2023

Street Art In Sectional Areas

Okay, now for the few cases of non-murals (street art and graffiti art) painted in sectional areas; that is, possible cases of street art as a direct addition or alternative to murals.

These are all interesting cases in one way or another. Some, we think, can be explained away, and some didn’t last very long, which demonstrates the competition between the purposes. But a few more clearly falsify our blanket claim that street art does not (yet) compete with murals.

In 1987, Bob Marley was painted in Springhill (CNR west Belfast). It was painted by a mural artist, Mo Chara Kelly, who painted it on the wall of his own house because, although the ‘Uprising’ theme might resonate with the locals, he was not sure that it was in keeping with the (political) murals in the street: “The Bob Marley mural, however, was painted on the side gable of my own house. I could get away with it there. I didn’t want to go up to somebody else’s house and say, “We’re painting a mural” and then stick Bob Marley up! And then have the neighbour come out shouting, “Mo Chara, I thought you were stickin’ something up about the struggle!” This was my personal thing.” (Painting My Community p. 86; free pdf available on-line). As such, this is a counterexample to our general claim, though it comes from a muralist and not a street artist and Mo Chara is here using a very narrow definition of “mural” – with a little lattitude, a mural entitled “Uprising” could quite easily qualify as a mural.

Street artists Friz and Hicks were hired to paint in PUL east Belfast in 2012. The support was from the East Belfast Arts Festival “in conjunction with the Lower Castlereagh Community Group, East Belfast Partnership, and kindly funded by the Lloyds TSB Foundation”. Friz’s piece was in Lord Street, site of many murals but had an explicit “community” message and was in the style of a kids’ cartoon.

However, the most we can say to bring the Hicks piece (shown below) into line with our thesis is that the immediate space for it is one that for a long time had been free from prior murals and indeed was being turned into C.S. Lewis plaza. So, there’s a sense in which this is not a sectional area. But this is a rather weak rejoinder, and despite the “Newtownards Road” in the top left, it’s not a community piece; the scene depicted is a countryside and the woman is carefree nature-lover (in fact, a California muse of Hicks’s – personal conversation). So, the primary effect of the piece on viewers will be “Whoa! What’s that doing here?”

In 2015, the IRSP/INLA’s tribute to Miriam Daly in Beechmount was replaced by an artwork – by visual artist and illustrator, Oliver Jeffers – to be used in a music video. Is it street art? Commercial art? Anti-social (i.e. inwardly-directing) inspirational slogan radically challenging the history and character of CNR west Belfast? In any case, the wall was soon returned to its former function in 2016 (image on the right).

In 2016 writers ANCO and CASP wrote in Islandbawn St and in Linden St. Geographically, these pieces are squarely among sectional murals, in republican Beechmount and lower Falls, respectively; compare these with the ‘eagle’ piece at Vogue hairdressers on the edge of Andersonstown, shown above.

This is their work in Islandbawn Street, in (CNR) Beechmount; it did not last beyond May 2018, as can be seen on Street View.

And this is their piece in the (CNR) lower Falls; it was replaced in 2018 by a Saoradh mural.

The collective known as the Belfast Bankers (previously called “The Loft” (Fb) and based in North Street in the city centre) were street art’s most bold move out of the city centre and into a sectional community, in this case, PUL Newtownards Road (east Belfast). Further, the pieces done for the Hit The East festival of 2017 were tucked safely out of sight in an alley, and painted all together. One piece, by emic, was, however, on the main Newtownards Road, next to the Bankers’ home in the unused Ulster Bank building. The art did not last two years before being painted out.